When I met Saadio one Saturday afternoon, the stifling heat of 27 degrees prevailed in the Mamelles district, north of Dakar, where the artist has his workshop. Located just 10 minutes from the sea, the sea breeze still refreshed the atmosphere.

With the 15th edition of the African Contemporary Art Biennale just weeks away, the artist is preparing to exhibit at the Senegal Pavilion of this major cultural event. Amidst his numerous phone calls and deliveries of paintings intended for the Biennale, I have the opportunity to meet him.

Clad in blue pants matching his black and blue plastic clogs, Saadio strides confidently through his cramped workshop, located on the first floor of a building. His glasses are secured by sturdy cords, and black traces marked his forehead, memories of years of prostration and prayer.

“Here, it’s quieter,” he said to me.

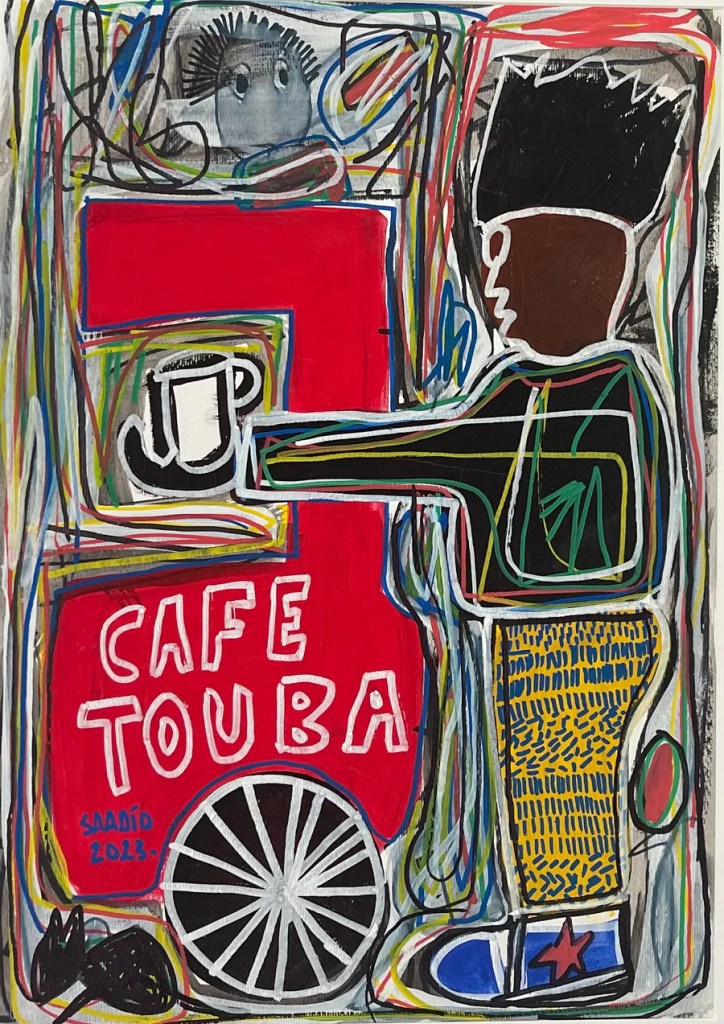

Upon entering his workshop, I am transported into a vibrant universe animated by the paintings that dominated the space, almost blocking the passage. The different urban characters captivates my attention. Sometimes on a motorcycle, on a Vespa, in a taxi, or on the “cars rapides.” I felt like I was, outside on the streets of Dakar. “Transportation is the problem we face in Africa,” he says.

The floor is littered with paintings, some hung, others unframed, drawings scattered here and there – it’s the welcoming decor. Various pots of paint, markers, and poscas are strewn beneath his work table. On that very table sits an impressive painting. A piece slated for the biennale. But not quite finished yet.

I’m privileged to witness the “finishing touches” the artist applies to his work. The final strokes of markers – sometimes bold, sometimes restrained – before it unveils itself to the public eye.

Ancestral Symbols and Contemporary Reflections

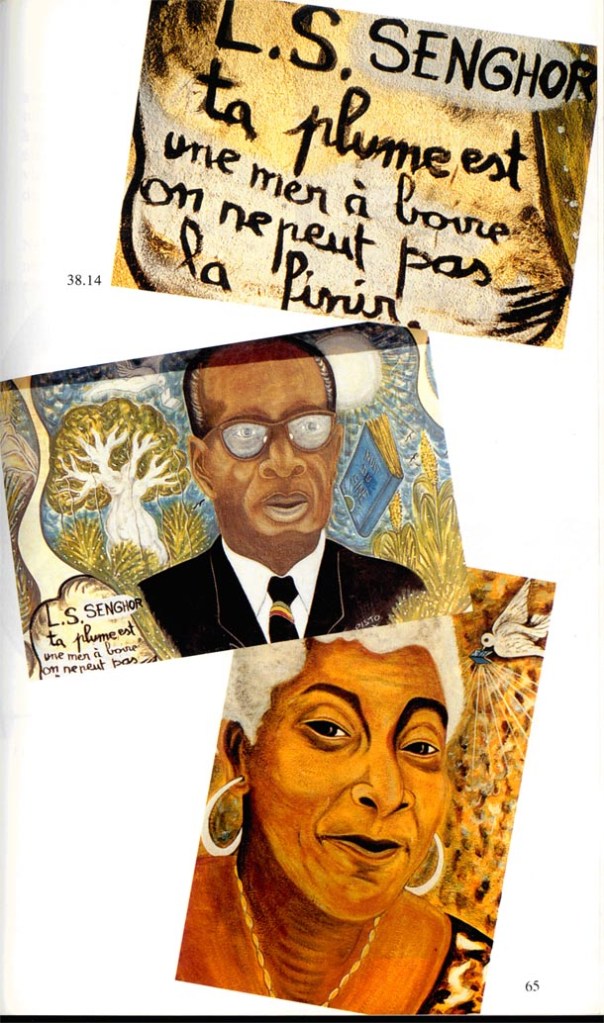

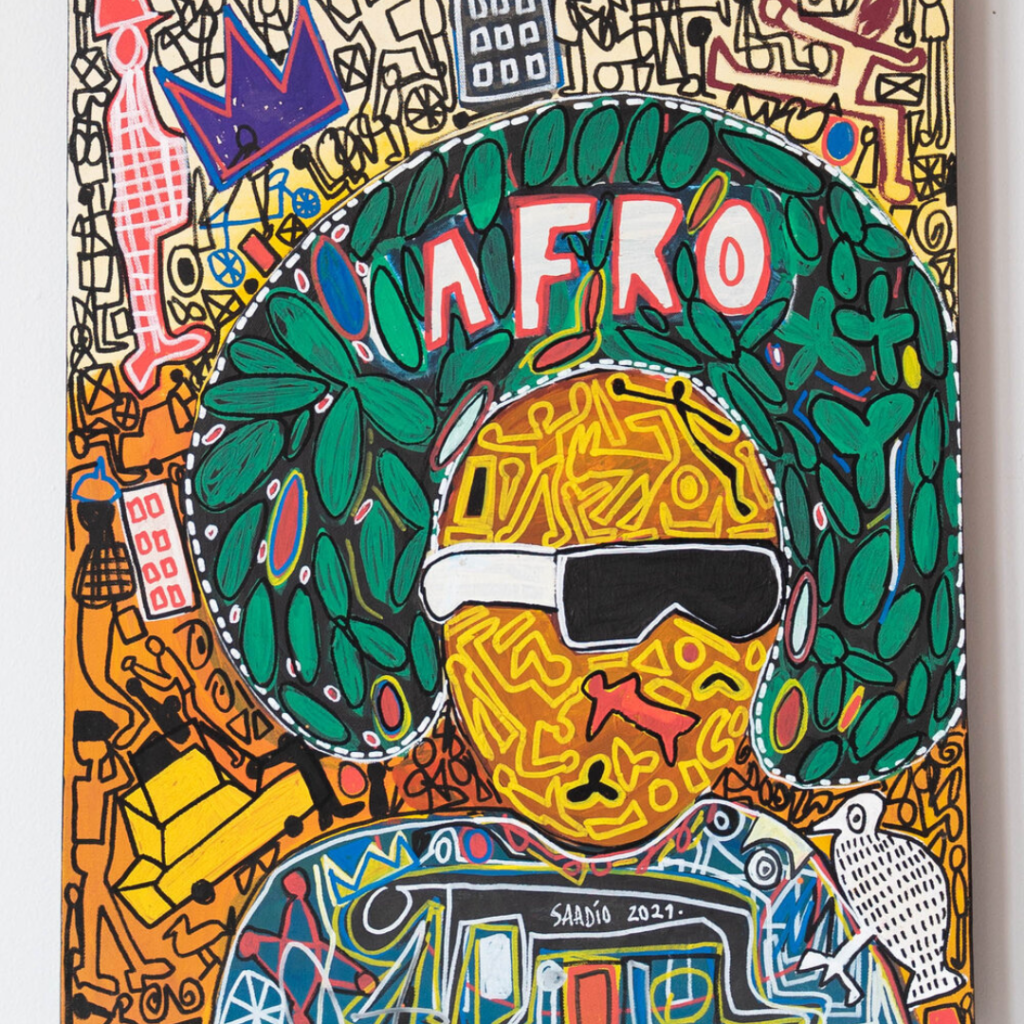

As an artist, Saadio draws inspiration from both his immediate environment and his African roots, crafting works that capture not only the political zeitgeist of his country but also the ancestral values of Africa. His piece from the “Africa My Home” series, intended for the biennale, reveals a deep contemplation of his African identity.

Evident in the piece are the ideograms he portrays – symbols reminiscent of the coded communication systems of the Peul shepherds of yore.

“These symbols were inscribed on animals to indicate ownership. Or to guide a lost Peul shepherd on how to locate his wandering herd,” he explains.

Born in Senegal in 1965 and father of five children, Saadio originally comes from the Fouta-Djalon region, mainly inhabited by the Fulani people, in the Republic of Guinea. In his work, every meticulous detail evokes the symbols of African ancestors, and every brushstroke represents a bold declaration of their heritage.

“I am an African artist,” he utters as he continued to sketch. Saadio aims to tell more about Africa through his art. The ancestral Africa. Its values. Its customs. Its traditions.

But he couldn’t help but look around him, to be the messenger of his contemporaneity. Thus, he also integrates the political news that is debated and contested in taxis. “Diomaye-Sonko,” a subject dominating discussions in the recent Senegalese electoral context, finds its place in his work.

The colors he uses are fearless and vibrant. African symbols are aestheticized. Life overflows from his characters. The presence of a slot machine testifies to references to consumer society.

In this lively work, the Senegalese artist plunges us into a visual dialogue between the ancient and the modern, between protest and the perpetuation of values, between rebellion and ancestral customs, between revolt and the preservation of established norms.

If the Senegalese painter is concerned with expressing his Africanness in his current themes, it is because throughout his artistic career, he has only told the story of the street. A street he knows well, having lived there for several years after being forced to leave the family home where his polygamous father viewed his artistic impulse unfavorably. Saadio was 22 years old when he began his journey on the streets.

His beginnings…

In the street, he frequented Cape Verdean decorators who lived in his neighborhood, in Sicap Baobab. They embellished shops and businesses with brands such as Coca-Cola, Fanta, Nescafé, Vitalait… But they didn’t let him touch the brush. The young Saadio, contented himself with observing, while being fascinated.

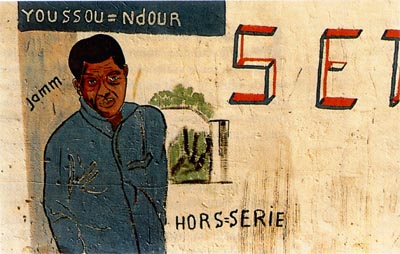

It was in 1990, during the “set setal” movement (meaning to clean up in Wolof), that he first painted a wall fresco with his decorator friends. This socio-political movement, of unprecedented magnitude, arose in a difficult economic context, marked by a policy of structural adjustment, resulting in the partial disengagement of the senegalese state in several sectors, including sanitation. The idea for the young people of his time was to reclaim their living environment, to clean it up, and in doing so, to beautify the walls.

« I swapped my technician’s

screwdriver for the paintbrush »

When Saadio painted this fresco, the sounds of “Set,” a song by Youssou Ndour, resonated within him. This piece by the Senegalese musician is known to have been a catalyst for the movement.

But it was only in 1997 that Saadio decided to dedicate himself entirely to art, after spending five years as a technician in an electronics company, located in the residential and business district of Point E, in Dakar.

“Our office was right next to the studio of the painter Kalidou Kassé, whom I frequented during those 5 years. And every day when I saw him paint, something vibrated within me. I couldn’t stop drawing. My boss noticed this and asked me to choose between work and drawing because I even drew at work. That’s when I swapped my technician’s screwdriver for the paintbrush,” he recalls.

He then joined the workshops on Ngor Island where, for several years, he learned alongside the painter Amdy Kré Mbaye and his nephews.

Basquiat and Saadio’s Artistic Awakening

Saadio began his career by organizing festivals on Ngor Island. He also participated in several editions of DAK’ART OFF. He exhibited in a group exhibition at the Galerie Africaine in Paris in 2004, under the direction of Aude Minard, a gallerist. In 2008, he represented Senegal at the International Exhibition of Zaragoza in Spain.

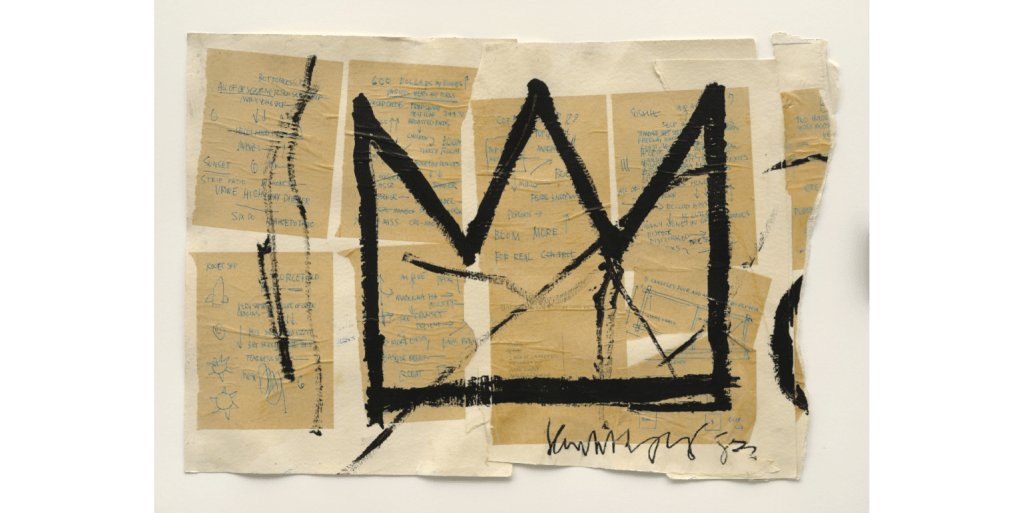

Despite his artistic commitment, Saadio had not yet received significant critical recognition. But everything changed when he discovered the work of the African American neo-expressionist genius Jean-Michel Basquiat, through a book given to him by one of his friends. It was in 2009: the Senegalese painter was 44 years old and Basquiat and the american icon of street art and graffiti had been gone for 21 years.

Like Basquiat in New York, who left his family to find himself in the streets, Saadio also wandered the lively streets of Dakar, breaking free from the family cocoon. Tensions with his father, similar to those of Basquiat, also marked his path. In the streets, Saadio absorbed the energy of concerts, the decor of hair salons, graffiti, the ambient noise, the billboards of dance parties… just as Basquiat had done in New York.

Saadio’s paintings are scattered everywhere in his workshop. Their expressive lines, iconic symbols, and palette of vibrant and bold colors undeniably evoke Basquiat’s style. I can notice in several of Saadio’s works characteristic elements of Basquiat’s art, such as scribbled texts and crowns.

In addition to stylistic similarities, Saadio appropriates themes dear to Basquiat such as music, the city, identity, Africa, and politics. Basquiat’s influence is tangible through Saadio’s works.

—-

How did the discovery of Basquiat influence your painting?

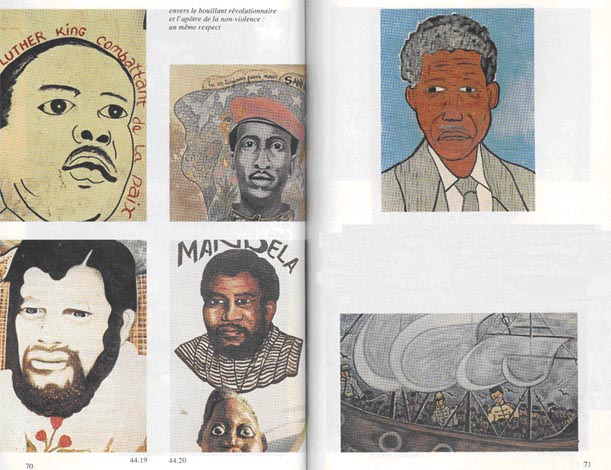

Saadio: By reading about his carrer, I saw myself. His journey inspired me enormously and led me to observe the walls of Dakar with a different eye, based on what he said about the walls. I went out into the streets and began to listen to the walls. The walls were talking to me. Plus, our walls in Africa have more artistic elements than those in New York. So I tried to go communicate with the walls, with the drawings on the walls of Dakar. I dialogued with the murals, the graffiti, the children’s drawings that were on the walls. In 2012, when the situation was tense in Senegal and the Yen A Marre movement was born, I looked at what the walls were saying to make collections.

What specific aspects of Basquiat's work struck/inspired you the most?

Saadio: Almost everything about Basquiat spoke to me. But one of the elements that is very present in my works and was also recurrent in Basquiat’s works is the crowns. Some customers tell me, ‘We love your paintings, but get rid of Basquiat’s crowns.’ The other element is the faces. Because he painted his faces without form, without calculation, as he felt. And that also inspired me. This form of raw art spoke to me.

"Saadio, the Senegalese Basquiat," is this a good description of you?

Saadio: That’s how a lot of people nickname me. But as I matured in my painting, I surpassed Basquiat. Now, I am Saadio. Certainly, he is more famous than me, but I downplay his work because I aspire to surpass it. That’s my philosophy. You have to dream. I don’t want to be called Basquiat anymore because I am moving towards something else.

Towards what?

Saadio: Now my themes are “Africa My Home,” I try to promote Africanness. I want to bring more Africanness to my works. Not Basquiat.

—-

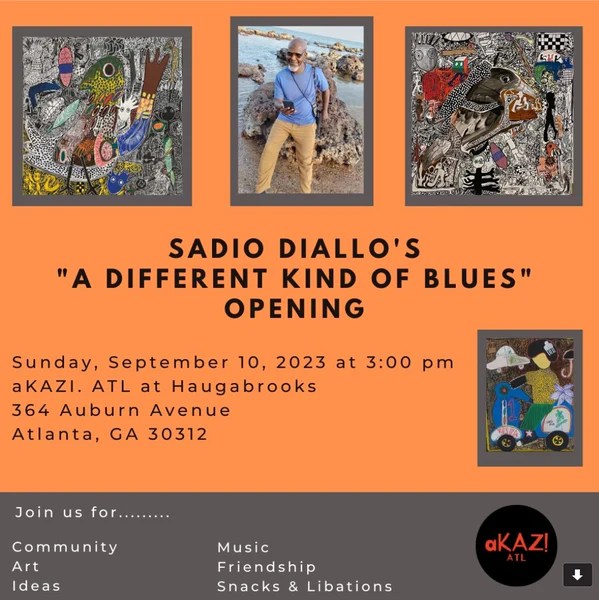

Saadio’s Key Exhibitions

Although he wishes to explore new artistic paths, it is clear that there has been a significant change in his career after his discovery of Basquiat. Indeed, the years following this “encounter” coincide with international recognition from art critics. His collection “A Different Kind of Blues” was presented in 2023 at the Akazi Gallery in Atlanta, United States, illustrating his artistic evolution.

His participation in exhibitions such as “Intertwined Narratives” at the African Art Beats gallery in Washington DC in 2024 and his selection for the National Visual Arts Salon in Dakar highlight his growing recognition in the art world.

His solo exhibitions, such as “Microcosms” in 2021 and “City Trip” (2017) at the Out of Africa gallery in Sitges, Spain, reflect his continued exploration of various themes and his mastery of diverse artistic techniques.

The addition of a Saadio artwork to the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts of Murcia in 2019, as well as its inclusion in their catalog of contemporary African art, testifies to the increasing recognition of his work on the international art scene. In 2011, Saadio also participated in a group exhibition in Fribourg, Germany, further strengthening his presence and recognition in the international art landscape.

The artist, who once mentored several young people, now prefers to work alone. “I no longer wish to take on apprentices because I find it uninteresting when people appropriate my ideas and themes without acknowledging their origin. The younger ones seem unwilling to face difficulties and lack patience,” he confides with disappointment. Who then will be his potential successor? Perhaps his son, Ibrahima, 21 years old, whose paintings litter his father’s workshop and whose artistic style presents great similarities? He looks intrigued to see me in his father’s workshop when he bursts in. But he kindly takes a photo of me with his father as I bid farewell to the place.

Leave a comment