When entering Kara Fall’s studio, a soft jazz melody fills the air. Posters of famous blues and jazz figures adorn the space, along with his keyboard where he plays music between paintings. Fall’s abstract and figurative works, infused with his malian heritage, often bear a touch of jazz, adding a musical and rhythmic dimension to his art. Born Ibrahima Nabi Youbi Coulibaly in 1971 in Niayes Thiokers, the neighborhood that hosted the first Village of Arts, his body of work spans painting, sculpture, interior design, and installations. He is a self-taught artist who has been part of the art scene for 30 years. For our series “What is Art,” DakArtNews met him at the Village des Arts.

————————————–

If your child, who sees you working, asked you what art is, what would you say?

Good question because in Africa, when you leave your family to pursue art, it is often considered a career with no future. That was the perception when I started. Nowadays, mindsets are changing. I believe that every human has art within them. I can’t precisely define what art is. In my practice, I start from concepts that come to me naturally. One does not become an artist; one is born an artist. I think life in general is art. The way we come into the world as humans, the need to live in a community, and the duty to protect the environment—all of that is art to me.

Is beauty something you pursue in your creative process?

Yes, absolutely. In any concept we develop, we may have the vision, but making it accessible to others requires a pursuit of beauty. It’s important. When women go out to celebrate with their friends or their spouses, they beautify themselves. When we attend events, we make ourselves look good.

Is beauty more important than the message?

The message is the foundation. But a good message needs to be aesthetically pleasing to be perceived. You can have great messages, but if you don’t have beautiful means to present them, they won’t be impactful. Humans are sensitive beings who need beauty. When they encounter a beautiful work of art, they accept it because something emanates from it that resonates with them.

Music is the foundation of my artistic creation.

Why did you choose to become an artist and not something else?

When I was 15 or 16 years old, art already fascinated me. When I saw artists in art centers, I felt they had a certain detachment from this crazy world. They had created a magnificent retreat where their minds weren’t stressed. This isolation and detachment charmed me a lot in the art world. I was young and searching for balance, for something that could save me. Art saved me in the sense that, as an artist, you control time and keep busy. Art allows me to write like a writer. It helps me forget time in this world of war, division, and the constant chase for money. In my studio, I’m on another planet that transports me and shows me things to express.

Can you tell us about your artistic vision and the message you want to convey through your art?

I never try to convey messages. That’s not my approach. I live in my studio and share what vibrates within me: the music and the images that come to me. When I wake up and stand in front of a blank canvas, I have no preconceived idea of what journey I will take with it. I just play my music and do my usual activities, and it comes naturally. Music is the foundation of my artistic creation. I can’t work without music accompanying me, especially jazz, blues, soul, funk, and afrobeat. It’s essential for me. These energies transmit to me what I want to express on the canvas. Music makes me dance on the canvas. It guides my artistic creation depending on the genre I’m listening to while painting. If it’s jazz, I can be jazzy on my canvas; if it’s blues, my canvas will have elements of blues. My relationship with jazz goes way back. I initially wanted to be a musician instead of a visual artist. But at the time, in Dakar, I couldn’t afford a trumpet. I couldn’t find one in the markets. It was only when I went to the United States, to Boston, in 2009, that I got my first trumpet. I stayed in the United States for eight years.

How did your time in the United States influence your art?

I remained the artist I was before leaving Senegal. The United States showed me many things. I visited the MoMA in New York, the Metropolitan Museum, the Guggenheim Museum, the Modern Art Museum in Santa Barbara, and many others. That was my world. The arts scene in America really interested me. Although I exhibited a lot there, I remained the artist I was in Senegal. I dislike influences. I always seek something that comes from within me. I don’t want to resemble anyone else. The universe is immense, with many unrevealed secrets. If we limit ourselves to another’s creation, it’s like not touching those small grains of secrets in this world.

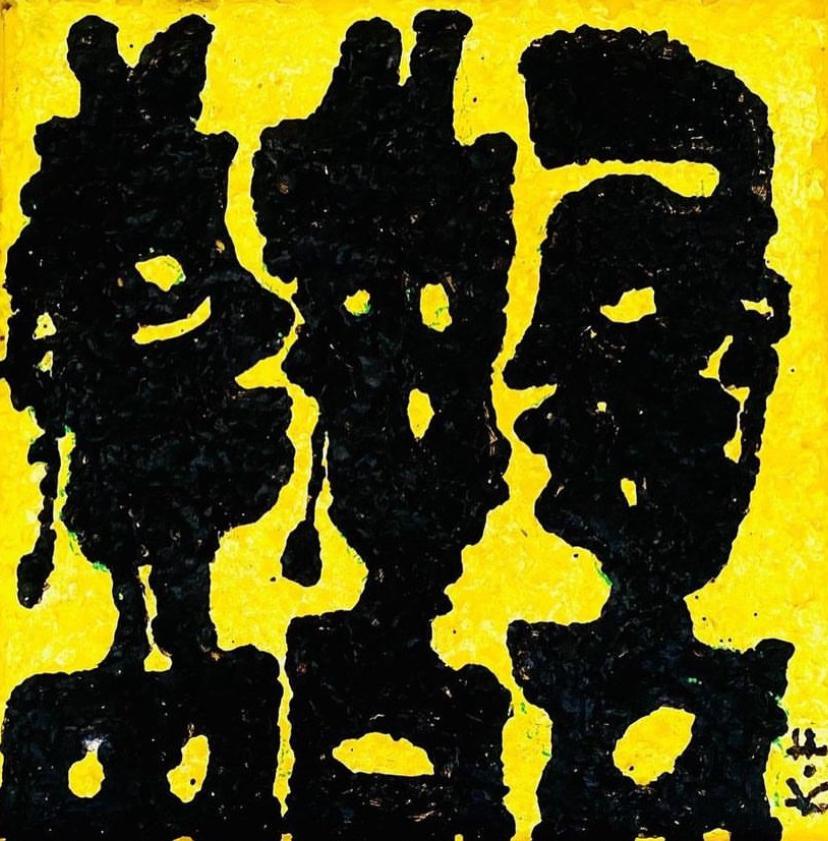

I notice that some of your paintings have figures that resemble masks. Can you tell us more about that?

The Dogon world in Mali inspires me a lot. I work a lot on that. What I paint comes from within me. These are not masks that exist materially. I see these masks in my inner world and bring them out onto the canvas. They come to me naturally. It’s an entire inner world that inhabits me and manifests in my work. I am Bambara, and my parents are from Ségou. I beleive to have the heritage from the Dogon world because, when I was young, my mother would tell me to go to the Dogon country because when she entered my studio, she would say I was painting the Dogon world, even though I had never been there.

What are your thoughts on classical african art?

I have seen many of the pieces our ancestors sculpted in major museums in the United States or Europe. Before seeing them in person, we couldn’t imagine that our ancestors created such monumental works. Back then, when they created, they didn’t talk about Fine Arts. They didn’t consider themselves artists because they did it naturally, in connection with spirits and genies. When President Senghor organized the First World Festival of Black Arts, the idea was to show that we Africans are not savages who grew up in the forests without any knowledge. We have an art that dates back a long time, and the aesthetics were there. The idea was to show that we are different, but we must be respected for who we are. In my art, I share the art of living together, whether black or white, to transcend borders.

What are your current projects?

I’m in my studio; my projects are my studio, which is my laboratory. When I show my works, it’s like moving my studio. I’m much more in that approach. I’m not too involved in the market. I don’t like what I do to become merchandise.

Leave a comment