We are in a bright garden with tree trunks assembled and slender metal rods. The sculptures, which are raw pieces of wood and rusted metals, stand in a vertical position, pointing up towards the sky like trees or plants in their gesture. Metals shaped like leaves and stylized canoes are attached to the rods, lending an artistic, distinct beauty to the ensemble. This afternoon’s natural light brings clearly out the opposing textures of wood and metal and creates a visual harmony.

Their arrangement in a circle around a middle point, as with many of the sculptures, reinforces further this impression of growth and vitality and makes everything fittingly coordinate with the silent environment of the yard.

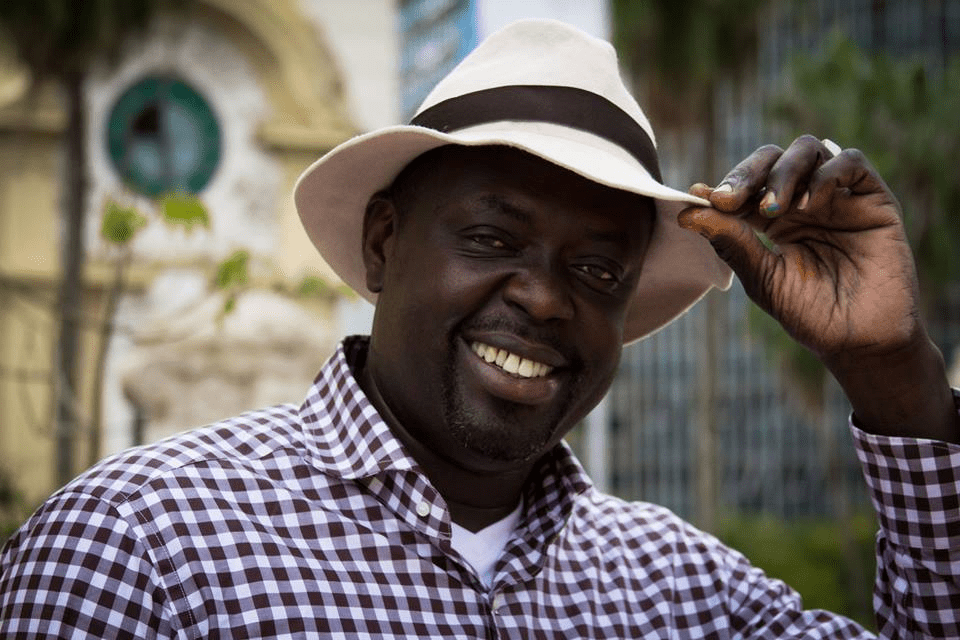

These are works by Momar Seck, 55, with whom we are greeted upon entering Pom Bi (The Bridge, in Wollof), an artistic and cultural space of this Senegalese artist. Pom Bi intends to establish a link between Switzerland, where Seck spent 25 years, the World, and Senegal through arts.

Photo Credit: Dakartnews.

Originally from the Lebou community, a fishing community inhabiting a portion of the Senegalese coast, the canoes in his sculptures bring back memories of his childhood and the heritage of the ethnic group to which he belongs. They represent fishing, the main activity of the Lebou people. But beyond this cultural reference, the canoes evoke travel and migration. Many in Senegal use such boats to try and reach Europe; often, people risk their lives, of which many have perished. Even though Momar Samb did not leave his country by sea, these canoes are able to symbolize the artist’s journey—both physical and metaphorical.

Photo Credit: Dakartnews.

Tree trunks put together to indicate the individual show how every person is a bundle of diverse experiences and qualities. Held by metal rods, the trunks give form to an essential social bond in society, showing the goal of the artist: wanting to bond and create meaningful connections despite differences.

If a wooden rod were missing, the structure would change, upsetting the balance of the whole, hence the contribution of each unit to the whole. This approach shows the artist’s intention to assert that every culture is important. An equally important message that this art passes is the aspect of equality. As such, the wooden rods are of a similar size. His artistic approach resonates with Édouard Glissant’s “Tout-Monde”, where every person and culture is understood as part of a global, connected totality.

Similarly, wood, metal, even textile—every material communicates in the work of artist Momar Seck, seeking out the connection he wants to make. His fascination with recycled materials dates back to his childhood.

Photo Credit: Dakartnews.

Already at the age of 4, Momar was obsessed with objects. In the streets of Bargny (15 km from Dakar), where he grew up, he used to gather all objects he could lay his hands on just to have something from which he could make something else or for rearranging his home space. “I created canoes out of pieces of paper,” he says, insisting that his current sculptures are reminiscences from those childhood moments. For him, creation was a natural way of living and being through the object.

After high school in 1990, having a career in the arts became a serious family debate, as it is with many artists in Senegal whose families often show reservations over artistic professions. To address these concerns and provide reassurance to his family, Momar attended the École Normale Supérieure by competitive exam to become an art teacher. This allowed him to pursue courses in art as well as training in art education so that he could follow his passion in the field of art while finding a secure career pathway.

He took part in the first contemporary art biennale in Dakar, in 1992, and won the Argentina Ambassador’s Prize, which became a source of motivation for him. It was in 1996, after having met some Swiss people during the Dak’Art, that he decided to apply to the Geneva School of Visual Arts. It was thanks to a scholarship from the Swiss Federal Commission that he could pursue a postgraduate programme in Switzerland, where he discovered new contemporary art approaches.

In Dakar, I had acquired the basics of creation, layout, staging, and artistic development. Coming to Geneva, I was more in the face of this new reality that is contemporary art. The way of presenting my work was different. I began to introduce the notion of installation into the work, which I didn’t do before. I had come to consider gigantism, monumental sculptures in my work.

In these regards, the artist affirms that the forms of his artistic writing—being in a new culture and a new environment—have heightened sensitivity in themes revolving around unity and diversity.

“These messages, I would say, became more pronounced outside Senegal because that is where I felt the difference, the confrontation with other cultures. That is where I realized that we needed to forge bonds. Because we don’t understand why things don’t work out. Why people look at others in a certain way,” he explains.

He also remembers that he became acquainted with works from artists such as César, Jean Tinguely, who worked with metals, and Gustav Klimt, among others. It was also in Switzerland that he intensified his work in painting.

A few paintings are hanging in the rooms of his artistic residence. The vividness of colours seizes the viewer: from yellow to blue, yellow ochres, oranges with pieces of fabric glued on. “It’s the colourful diversity,” he says. Each one of these works becomes at once a unique representation of this diversity but gives an idea of the unity and fragility of our bonds.

Momar Seck adds textile in his paintings, not only for the aesthetic side but to address cultural identity. In many African cultures, there is a social and symbolic function tied to the textile, and these identity markers he wants to represent in both his sculptures and his paintings. “As a child, I was always fascinated by my mother’s clothes, the diversity of patterns and colors,” he explains.

While his creative career has given him international recognition, he is now concerned with a role that surpasses creation: “The artist has to develop relations among people, communicate, coordinate, and unite,” he states. This vision led him to organize artistic residencies and civic initiatives—like building classrooms and providing computers. “The artist must be a social pillar,” he insists. That’s how he sees his role and his return to Senegal since 2022.

Youssou Ndour’s music helped me

Momar Seck

during the most difficult moments abroad.

Inside the Mind of Momar Seck

What does art mean to you?

Art is the natural and personal way I find to express my daily realities, my concerns, my desires, my moments of sharing. I see it as a fundamental means of preserving our cultural realities, a fundamental way to leave a mark on our lives. Civilization may disappear, but art is the essence of a society. Civilization fades, but culture remains, and art is a pillar of culture. My initial approach to creating is like the desire to eat or drink. It’s a vital necessity in the sense that if I don’t do it, there’s a void, something missing.

Do you create art to communicate a specific message?

This isn’t the starting idea; it’s an element that gets added to give meaning to the sharing with the public. I’m interested in several themes, such as the environment, for example. The environment we live in isn’t the same as in Europe. To protect it, we need different ways of action. The first approach is more personal, a desire for personal satisfaction, an act that could be considered selfish.

What about beauty?

If I want to make a sculpture, I think about the sculpture, not about beauty. And my finished sculpture can be considered beautiful, even if that wasn’t my initial idea. Because I don’t want to be guided by the desire to satisfy others. If I aim to create something beautiful, it’s as if I’m introducing someone else into this reality. The public appreciates the work and gives it the qualification of beauty.

If you could collaborate with any artist, who would it be?

Abdoulaye Ndoye and Djibril André Diop.

Is there a recurring dream or vision that inspires your artistic work?

My dream is to always be myself.

Is there an object in your life that holds particular significance in your art?

Canoes and tomato cans. I also did a work on tomato cans. The fact that the object regularly changes its social function. For example, a coffee can here in Senegal, when it is emptied of its contents, we wash it and use it to drink water, and when it no longer works as it should, the aunt uses it to sell her peanuts. And the talibé (student of Quranic school) can take it with him to go from house to house. Then they are thrown in the trash, and I take them back with the idea of saving something to bring it back to life.

Is there a place where you feel the best to create?

By the sea. I paint here, but the sea would be the ideal place.

Which musician do you listen to while working?

Youssou Ndour. I like everything he has done. Youssou Ndour has not only been a singer for me but a companion during the most difficult moments I had in Europe. In the cold, in the moments of isolation in my studio. And his music created a direct link with Senegal. When I heard sounds that reminded me of songs my mother regularly repeated, it put me in a symbiosis with myself.

Do you have any rituals you follow before starting a work?

I always like to feel immersed in the space where I work. The first thing I do when I want to start working is to sit down and do nothing for one or two hours. That’s why when I come in the evening, I can work until 4 in the morning.

And how do you celebrate the completion of a work?

It is always a moment of fulfillment, a moment of satisfaction like an accomplishment. I often look at the piece, detach it from myself. I look at it as if someone else had done it. I never look at a work as if it is completely finished, because very often I come back to it to add something. And at some point, I tell myself I stop, it’s good.

What is the most unexpected material you have ever used in your works?

I can mention, even if they are not really unexpected, pieces of wood, textile, plaster, white glue. I work with these materials.

If there is an object you could transform into a work of art, what would it be?

Stack a large canoe and place it in a museum.

What is the emotion that seems the most difficult to represent through art?

None. I think everything that comes to mind can be represented in one way or another. Maybe for the viewer, it can be difficult to perceive the emotion but for me, the moment I express it in connection with that emotion, I consider it accomplished.

Is there a color that symbolizes your artistic vision?

No, it’s a multitude of colors. It’s the colorful diversity. It’s the multitude of colors to the point of saturation. My works are filled with vibrant colors.

If you could send a message to yourself at the beginning of your artistic career, what would you say?

Continue to be yourself and paint or work as you feel. I say this because the artist can be immediately diverted according to the reality of the market, the desires of others.

Is there a Senegalese story or legend that you would like to integrate into your artistic approach in the future?

We return to the Lebou culture. It is a culture of social cohesion and unity. The notion of sharing and solidarity is an important element in my work. When we were young, the houses were large and composed of several homes within. They were concessions that had a main entrance door, and behind there was a small door that we called “the pot,” the discreet entrance door. This door allowed people who wanted to help families in need to come and do so in the middle of the night and place it in front of the house door. From that moment on, every person you meet is a potential donor because you don’t know the identity of the donor. This aspect of social solidarity helps to strengthen ties and maintain the dignity of individuals.

What is or should be the role of the artist today?

The artist is a social actor, not just through his or her visual creations. We’re talking about creating links. The artist must develop relationships with people, but also develop connections between different people. I think of the artist as my grandmother who had her needle and thread for sewing. The artist has to connect things, coordinate, put things together, not tear them apart. It’s an important role, and that’s why my artistic work has a citizen participation component. I organize artistic residencies here at Pom Bi, but I also organize construction events in schools. I build classrooms and donate computers. It’s a social role. The artist must be a social pillar. Creation sometimes detaches us from society, but the artist must do his best to return to society. In the beginning, we’re seen as outsiders. If you continue to think exactly like everyone else, you can stop painting or creating. An artist must fundamentally think differently, conceive differently to bring something new. People often say it’s not art to develop social work. I say of course. When I see a straw building that I’ve transformed into a hard one, there’s a contribution in the spatial setting that can be considered as artistic production.

How do you think your art will evolve in the next 10 years?

I continue to do research. When I was accepted as a professor in Switzerland at the International School of Geneva, this need for research was there, which is why I did a doctorate in Strasbourg. This aspect of research makes me be a researcher all the time. Certainly, I have found a path for my work, but it can change while being the same. It can evolve into something else, in terms of the form of representation or setup.

DakArtNews

Leave a comment