In the midst of Medina, Dakar, where the rhythm of daily life and the pulse of creativity intertwine, Espace Medina emerges as a vibrant hub of artistic expression. Amidst the lively street scenes and the dynamic transformation of the neighborhood, this cultural space has been a cornerstone of artistic and social engagement since the 1960s. This journey reveals how Espace Medina not only mirrors the spirit of its surroundings but also stands as a testament to the power of art in shaping and reflecting community values and challenges.

Children play soccer on the sidewalk, oblivious to the speeding cars. A group of young people chat on a street corner, cigarettes in hand, sipping ataya, senegalese tea. Two young girls wave to each other across the street. Sheep, tied up, block the pedestrian path. The shrill sound of motorcycles, the hammering of a metal welder and the grinding of a carpenter’s saw combine to create an urban symphony. The Medina is a lively, vibrant district, even on a hot, sunny afternoon.

It was here that the ‘Espace Medina’ art and cultural space was established in 1996, within the confines of a family home that has been overflowing with artists and cultural intellectuals since the early 1960s. The area was even one of the venues for the 1st World Festival of Black Arts in 1966.

If we think of the Medina as a large villa, Espace Medina would be an essential room in it. And if we take the image of the human body, Espace Medina could be seen as an arm of the neighborhood, so much so that the energy emanating from it is a reflection of the street. This impression is confirmed with several people taking ablutions before entering a ground-floor room of the space, transformed into a mosque.

My feelings are further heightened when Artistic Director Cheikh Bamba Loum, nicknamed “Cheikha”, confides, “I could even sleep on the street here in the Medina, I feel so at home.” A stylist-designer, Cheikha is busy on the terrace, scissors in hand, ready to cut a fabric, while other members of the space are busy on sewing machines.

The diversity and number of objects here is striking: plastics, scrap metal, colorful busts, storm lamps and, above all, textiles. Some objects seem to be waiting for a second life. Others have already found their second life, in this veritable laboratory where everything is subject to transformation and experimentation.

For Cheikha, there can be no distance between artistic practice and the immediate environment, which is the Medina. This is what he calls “societal art”. This philosophy is reflected in the repainting of house facades in the neighborhood, an initiative undertaken by the members of the Espace Medina.

He adds: “I’m often misunderstood when I say that my vision stops at the Medina. I say this because if what I do doesn’t have an impact on the people of the Medina, where we live, then what I do wouldn’t make sense.”

Espace Medina and the Agit’Art legacy

Espace Medina’s approach follows in the footsteps of the Laboratoire Agit’Art founded in 1974, whose emblematic figure Joe Ouakam broke with the academicism advocated by Senghor, by promoting proximity to the people through artistic installations and performances.

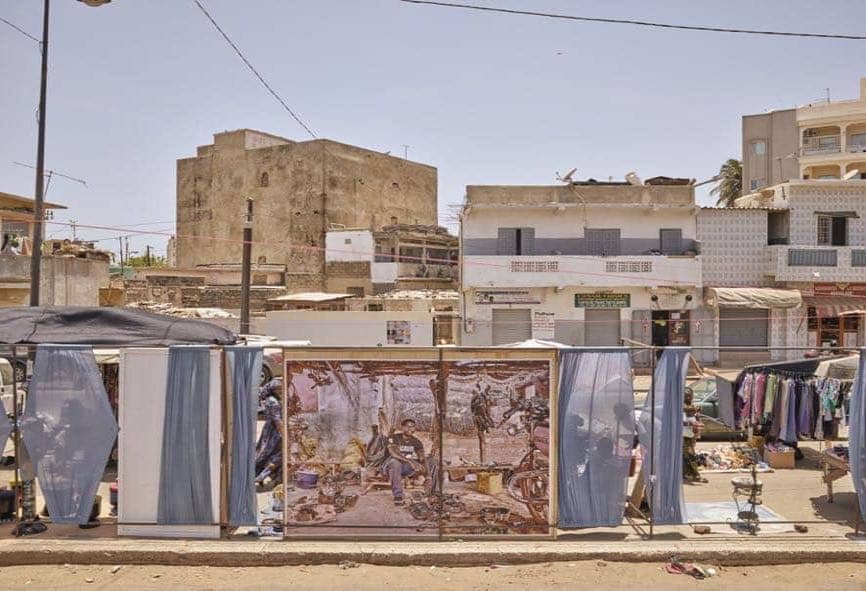

Building on this legacy, in 2018, during the Dakar biennale, Espace Medina participated in a project titled “My Super Kilometer.” The artists took over a canal usually occupied by merchants, placing photographs, paintings, and sculptures there. Peanut sellers, clothing vendors, shoeshiners, and other traders found themselves at the heart of artistic creation, becoming both subjects and co-creators.

“Old men, old women, children, everyone came out to see. It was extraordinary. We saw elderly people, usually confined to their homes, come out for the occasion. They felt involved,” recalls Beuz Fall, a self-taught artist who has frequented the space since childhood.

Two years earlier, in 2016, the exhibition titled “Nous dans Nous” (“We in Us,”) created during the biennale, had already highlighted the inclusivity of Espace Medina’s approach. For its creators, what makes art is the process and the story, much more than the final object itself. “When the cotton producer takes his cotton and transforms it, it’s not the fabric we buy that’s important, it’s the story behind it, the entire process,” explains Cheikha.

Moussa Traoré: Upcycling Metal into Symbolic Art

On the first floor of Espace Medina, I find Cheikha’s uncle, Moussa Traoré—who initiated the creation of this cultural space—surrounded by his metal sculptures and chatting with his friends. His use of recycled materials conveys a message about sustainability and the revival of traditions in a modern context.

His pieces are imbued with symbolism and emotion; for instance, his large pirogues, deliberately half-sculpted in the center of his studio, evoke the deadly clandestine migrations in which many young people from his country lose their lives trying to cross the Mediterranean Sea.

Some shapes of his artworks recall traditional African sculptures and masks, particularly those of the Dogon in Mali or Baoulé people in Côte d’Ivoire, known for their elongated and stylized figures.

While Moussa Traoré draws inspiration from his african heritage to create his pieces, he is also open to other cultures. The artist has a special relationship with Italy, where he regularly exhibits his work.“I was inspired by Dante’s text on Inferno to create this piece,” he says, showing me a sculpture influenced by the first part of Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy. The sculpture, an interpretation of the italian poet’s Inferno, shows the rear of a metal horse, within whose belly dolls are glued together, their bodies and faces covered with black paint and fabrics. In the background, a piece of red fabric symbolizes fire.

The artist here interprets in his own way the suffering of heretics as noted in Dante’s sixth circle of the flaming tombs of hell: “After living confined in error, illuminated by a false light, they lie in open and eternally burning tombs.”

Other sculptures by Traoré feature angles, straight lines, and curves that intersect with a segmentation of elements reminiscent of Cubist experimentation—a comparison he has heard before and that brings a smile to his face.

His creative process, which values the recycling of raw materials, is also a discourse on environmental protection, dear to the artists of Espace Medina, for whom recycling is fundamental. But this is challenging as the neighborhood changes with gentrification. “The neighborhood has changed. Now there are buildings everywhere, which is not good for the environment. The Medina has become commercialized. The newcomers don’t know the soul of the neighborhood,” regrets Beuz Fall. “If we’re not careful, there will soon be few family homes. We only have art to try to change things. Art is our strength.”

Preserving the Essence of Espace Medina

One of the other concerns is the renewal of generations. The artists of Espace Medina are no longer very young, and the question of heritage and transmission arises. When I ask Cheikha how he sees the space in 20 years, he remains perplexed. “Will the next generation understand what we will leave them?” he wonders. “Because so far, we are not really understood. Won’t the next generation sell the house?” (laughs) But his wish remains clear: “I want this space to become a place of knowledge. It won’t necessarily be a school or a library, I don’t yet know what form it will take. But the essential thing is that it remains a space of knowledge.”

With the Contemporary African Art Biennale of Dakar starting on November 7, 2024, and themed “The Wake,” the artistic director is contemplating creating a “wake-up” call on mobility. This is set against a backdrop where visa applicants are being rejected without valid reasons, forcing them to take risks through dangerous boat journeys. “If art does not denounce this injustice, then what is the purpose of art? ,” he questions.

DakArtNews

Leave a comment