DakartNews has the pleasure of speaking with a key figure in the Senegalese art scene—a curator and artistic director who has, over the years, established himself as an essential expert in the field of visual arts. Wagane Gueye is the initiator of the Doxantu Art Tour, an artistic and cultural journey through Dakar, the Petite Côte, and the southern region of Casamance. These cultural tours aim to highlight the artistic and heritage richness of Senegal by creating bridges between artists, cultural spaces, and their audiences. After spending nearly a decade in France, he returned to Senegal in 2015 to continue his work in cultural management, which began in the late 1990s with an art gallery. In this interview, Wagane Gueye shares his vision of the uniqueness and vibrancy of the Senegalese art scene. We also discuss issues surrounding the art market, private collections, and local initiatives supporting Senegalese artists. His insights invite us to rethink dominant perceptions of the African art market and shed light on a unique dynamic specific to Senegal, where culture and art play a central role in society.

What makes Dakar such an important place on the global art stage?

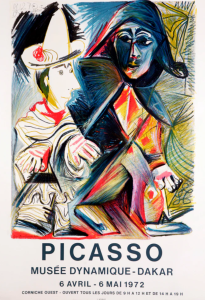

Dakar and Senegal’s strength comes from the leadership of poet-president Léopold Sédar Senghor. You have major nations like Morocco, South Africa, Benin, and others that view cultural policy as a true vision, a sort of soft power to bolster their country’s appeal. There is a dynamic in these countries, but Dakar’s strength lies in a very fertile history initiated by President Senghor’s vision. He was behind the 1966 World Festival of Black Arts, the creation of the Dakar School of Fine Arts, and the Manufacture of Decorative Arts in Thiès. He also established the Daniel Sorano National Theater and the Musée Dynamique, which hosted exhibitions of works by Chagall, Picasso, and others.

This cultural policy went beyond visual arts, as every facet of culture was promoted, supported, and administered with substantial backing from the Senegalese government. This rich history gave rise to artists such as Pape Ibra Tall, Amadou Ba, Younouss Seye, Bocar Pathé Diongue, Amadou Seck, Ibou Diouf, and many more. All this excitement culminated in the 1990s with the creation of the Dakar Biennale under President Abdou Diouf’s leadership. Dakar is an attractive place for art today. There has also been local patronage, like that of Victor Cabrita, the former director of the Cours Sainte Marie de Hann, who supported many artists and made his institution a place where art was present in the school’s curriculum and all its spaces. In my opinion, everything starts with Senghor.

But hasn’t government patronage stifled artists' creativity?

Senghor and the cultural movement of the time were often criticized for an overly noticeable state patronage of a newly independent nation. It’s true that the Dakar School was influenced by Senghor’s aesthetic vision, particularly his perspective on Negritude. Nonetheless, we shouldn’t dismiss this entirely. Despite his strong influence, other forms of artistic expression, like the Agit’Art Movement, emerged. This movement was created by Issa Samb, also known as Joe Ouakam, Elsy, Djibril Diop Mambéty, and other intellectuals. I don’t think Senghor was very resistant to criticism in the arts, perhaps more so in politics. For instance, President Senghor often engaged in discussions about art and aesthetics, and even after his presidency, he attended exhibitions, including that of El Sy, who was one of the pillars of Agit’Art. In retrospect, we can see that if Senegal occupies such a central place in the arts today, even ahead of nations more economically advanced than us, it’s due to this rich history. We must give Senghor his due credit.

“The Dakar School is the backbone of Senegalese painting”

What remains of Senghor’s aesthetic in contemporary artistic practice?

I believe the visual arts scene in Senegal is very pluralistic. Today, many young photographers have a solid approach, build impressive careers, have a distinctive aesthetic, and create works that are in tune with the times. There are also painters inspired by the Dakar School. Painter Zulu Mbaye once said in a panel discussion: “The Dakar School is the backbone of Senegalese painting,” and he’s right. We can’t erase this school. Major artists in painting, such as Soly Cissé, Viyé Diba, Babacar Mbaye Diouf, Mbaye Diop, and Arébénor Bassène, are all, in one way or another, influenced by the Dakar School, even though their styles may differ.

You mentioned that some artists create works that are "in tune with the times." What do you mean by that?

Many artists often follow trends, especially in painting. I don’t fault them for this. But, my conception of art is something that endures, where certain works are not instantly valued. I lament this trend-following phenomenon because art created on demand doesn’t last; it remains a passing trend. It’s more of an advice than a critique.

But isn't an artist free to create whatever they want? Isn't that the principle of artistic freedom?

An artist has the right to live from their art and create… Of course, when creating, one inevitably reaches a market. Nonetheless, I believe that artistic production should not be dictated by the market. I don’t want my words to come off as critical, but I think young artists should think about the future, not just the present.

Senegal is participating in the Venice Biennale for the first time this year. Does this continue Senegal’s rich artistic heritage?

This year, Senegal has a national pavilion at Venice for the first time. That being said, let me correct a misunderstanding. This is not the first time Senegalese artists have participated in the Venice Biennale. Works by Moustapha Dimé, Ousmane Sow, and Pape Ibra Tall have been exhibited at Venice. The great art critic and curator Okwui Enwezor showcased Fatou Kandé Senghor in 2015 at Venice for her film on Seyni Awa Camara titled Giving Birth. This shows that Senegalese artists have long participated in various editions of the Venice Biennale, the Documenta in Kassel, and numerous major exhibitions worldwide. I say this repeatedly: our history of visual arts parallels the independence of our nation.

Let’s talk now about the art market in Senegal. There are no auction houses, let alone major art fairs. Can we still speak of an art market?

We can talk about a market because the first client of Senegalese visual arts is the Senegalese government. Many cultural actors advocated for the 1% law. The late Jo Ouakam and lawyer Bara Diokhané were part of a collective that fought for the 1% law to be passed. The idea of this law is to assign 1% of state contracts to artists. The large ceramic murals you see under Dakar’s bridges were created based on this law during the Organization of Islamic Conference summit. Additionally, the Senegalese government has always made purchases for itself, for its high-profile guests, and for its spaces.

The Antenna Gallery, created by Marthe and Claude Everlé, one of Dakar’s first private galleries, was one of the main suppliers to the Senegalese government. President Senghor was also a collector. Furthermore, many Senegalese intellectuals and professionals, like Mayoro Wade, Abdourahime Hagne, Pierre Babacar Kama, and Bassam Chaitou, have collected art. The BCEAO also collected heavily in the 1990s. Some Senegalese marabouts (religious leaders), who are open-minded and economically inclined, have always supported artists, even beyond visual arts. The Dakar International Biennale (DAK’ART) is a space for sales and promotion for artists from Senegal, the continent, and their diasporas.

“There are more and more international galleries in Senegal today, especially over the past ten years. They wouldn’t exist if there wasn’t an internal market.”

These examples are from the past. What about the current state of the market?

Indeed. But, the works acquired back then can now sell for quite high prices, compared to those of living artists. The highest sales are made by major auction houses in Europe. When these auction houses create sales catalogs, they include all artists, which means that older works stay on the market, whether from Senegalese artists or those from Central Africa, like the Poto-Poto School. For example, Ouattara Watts, who isn’t from the new generation, is much more valued than many young artists today. In my reading of the market, I see it more as a finished product. Mansour Ciss Kanakassy, from the second generation of the Dakar School, has managed his reputation and position to be at the forefront of the international scene.

Doesn’t the fact that high sales are made in Europe show the insignificance of the internal market?

What I know, as a curator and artistic director with access to several private collections, is that Dakar has been very fortunate because many civil, political, and religious personalities have collected and continue to do so. Some contemporary collectors also continue to expand their private collections in Senegal. You can refer to the work of Joanna Grabski, an American art critic and historian, who shows, for instance, that artists have always had a close relationship with buyers and collectors, who visit their studios…

What about collectors in Senegal? How important are they to the local market?

Today, all the major exhibitions that take place in Senegal or abroad, which focus on our visual arts globally, even across time periods, are obliged to discuss with Senegalese collectors, who are quite many. For example, Senegalese architect and collector Habib Diene has about 1,000 pieces of art in his collection, which dates back to the 1980s. Other individuals also collect art. As a result, many families have inherited rich art collections and also sell certain works thanks to an existing underground market. This is the case with the families of deceased painters, like Souleymane Keita, Amadou Sow, Seni Mbaye, Alpha Sow, Ndary Lo, Ousmane Sow, Ibrahima Kebe… Their works are highly valued and are held by family members or Senegalese collectors.

But is that enough to consider it a market?

There are more and more international galleries in Senegal today, especially over the past ten years. They wouldn’t exist if there wasn’t an internal market. Additionally, many companies and banks collect art through their executives. We need to have a different perspective on the art market. You will rarely see a school in Europe owning a collection of 500 to 1,000 works of art, as is the case with the Cours Sainte Marie de Hann, in Dakar. So I think there is a Senegalese exception. Furthermore, artists from the first generations have always had their patrons. Each artist or group of artists is supported by a banker, a friend, or a business leader. In 2018, for example, when we were organizing the Les Empreintes du Temps exhibition, dedicated to deceased artists, we came across the collection of a former banker named Libasse Thiaw, who was close to artists like Joe Ouakam and supported his artist friends. We found some very rare pieces in his collection. In my opinion, those who should analyze the art market should do so from the perspective of Senegalese collectors.

An art market involves legal frameworks, trends, expertise, and valuation, noted Senegalese art critic Mbaye Babacar Diop in a column in Le Monde, asserting the nonexistence of a local art market. What do you think?

I have a different approach to this issue. I have access to collectors and collections. As an art curator and artistic director, I have access to the interiors of collectors and their heirs. Thus, I interpret the market from a local context. What has allowed many artists to thrive is that they have been supported by private Senegalese individuals, whether public figures or institutions. Diplomatic missions also have collections. So, for me, this must be understood within a local context.

What could be done to encourage the growth of the art market in Senegal? What changes are necessary to improve it?

The state has its spaces, for example the Museum of Black Civilizations, the National Gallery, the Place du Souvenir, and the African Renaissance Monument… But for us, cultural actors who wish to organize events in Senegal, it is difficult to access these spaces, whether for artists or curators, particularly due to the rental rates, which are somewhat too high. Cultural actors, both local and international, should have easier access to these exhibition spaces because that is where the market is also created: through the presentation of works, the renewal of programs, and the showcasing of the artistic scene in its entirety, both past and present. It must be said that the private sector is very dynamic, with the flourishing of galleries and international art centers, as well as spaces created by artists. There’s the Partcours initiative, led in particular by Koyo Kouoh of Raw Material and Mauro Petroni of the Almadies Ceramic Workshops, which created a gallery circuit—an event that allows buyers and even foreigners to come to the Dakar scene. All of this demonstrates the dynamism of the Senegalese scene. But what would be desirable is for the state to engage in discussions with the actors in the field to see how best to support them, notably by making spaces available. I believe that if institutions play this role of framework, support, and patronage, they can better help the dynamic scene we notice in Senegal.

DakArtNews

Leave a comment