There are collectors who amass artworks, and others who build connections. David Brolliet belongs to the latter category: for him, art is above all a human adventure, a means of forging bonds. His collection, comprising over 1,000 works accumulated over more than 40 years, brings together both icons like Jean-Michel Basquiat and Andy Warhol and major figures of contemporary African art such as Abdoulaye Konaté, Soly Cissé, and Pascale Marthine Tayou. He was introduced to contemporary African art in the 1990s through Romuald Hazoumé and Barthélémy Toguo. In Senegal, Omar Ba and Fally Sène Sow have been particularly significant to him. True to his philosophy, he only collects artists he has met personally. In Senegal, where he settled a few years ago, he plans to establish part of his collection, following the model of his initiatives in Geneva, New York, Dubai, and Paris. His ambition? To make private collecting a tool for sharing and promoting African artistic heritage. It is in his Dakar apartment, surrounded by works by Senegalese artists and artisans, that he welcomes DakArtNews to discuss his journey and his vision of the collector’s role.

Photo: Steeve Iuncker-Gomez

Can you tell us about your journey as a collector and your engagement in the art world?

I have been deeply involved in cultural life since a young age, through various activities and support for cultural institutions. In the 1980s, I had a political career committed to culture as an elected official in the city of Geneva, within a party then called the Liberal Party, now the Liberal-Radical Party. I played a significant role in the creation of the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Geneva, which exists today. As an elected official, I participated in the acquisition of the building by the city so that Geneva could own it—something I still consider an excellent decision. Later, as a collector, I donated works to the museum because I believe a collector’s role goes beyond acquiring art; they must also be a patron and a supporter of artists.

From the age of 12 or 13, my parents took me to museums regularly. However, I did not pursue studies in art history. In my collection, with a few exceptions—such as César, Jean-Michel Basquiat, or Andy Warhol—I have met all the artists whose works I own. I started with zero money, visiting galleries and asking to pay in installments because I couldn’t afford to buy art. My father could have afforded it, but he never gave me financial support. I was raised very strictly. He didn’t like contemporary art and would always joke, “How is your “art comptant pour rien” ‘(worthless’ art) doing?” He passed away at 60.

I was one of the first members of the Marcel Duchamp Prize alongside its founders and was also involved in ADIAF (the Association for the International Diffusion of French Art). Though I am a Swiss collector, I buy works by artists from all over the world, particularly African artists, especially Francophone ones. I strongly support the Francophonie because I believe our language is a valuable link, a richness that unites our distinctions and differences. Since I decided to settle in Dakar, I have naturally included Senegalese artists in my collection. If I had not found talent among them, I simply would not have collected them.

“Africa is the cradle of Art(…) I collect with my heart”

Textile

207 x 206 cm

© Abdoulaye Konaté, David H. Brolliet Collection, Geneva.

Textile

220 x 190 cm

© Abdoulaye Konaté, David H. Brolliet Collection, Geneva.

Why do you choose to collect only artists you have met personally?

That is an important question for me. Many collector friends call me asking if I can get them an Omar Ba piece, simply because they want an Omar Ba. When I ask them why, they say, “I need an Omar Ba in my collection,” because he is a trending artist. I respect that, but it’s not my philosophy.

For personal reasons, I haven’t really had a family life. I was an abandoned child, the last in my family, born much later than my siblings. In a way, my collection and contemporary art are my family. I have deep respect for artists, which fosters friendships. That’s why, beyond meeting them, I often interview them. I can’t buy an artwork if I haven’t spoken with the artist and engaged in a conversation. There have been artists I liked, but after discussions, something didn’t click, and I never bought their work.

Mixed media on cardboard

70 x 50 cm

© Omar Ba, Collection David H. Brolliet, Genève.

Is there an artist or a work in your collection that best shows your vision of contemporary African art?

Romuald Hazoumé from Benin and Barthélémy Toguo from Cameroon opened my mind to Africa, particularly through recycling and repurposing seemingly useless objects into artworks. This reminds me of artists like Tony Cragg or Picasso, who was inspired by African art to create his masks. Africa is the cradle of art. But here in Senegal, two artists have been particularly important to me. The first is Omar Ba, whom I met at the Geneva School of Fine Arts when he was working with cardboard. I thought, this guy is an alien. He rolled cardboard into sculptures—there were no traditional paintings. He made pieces with tiny perforations in the cardboard.

Wood and printing ink

43 x 40 x 23,5 cm

© Barthélémy Toguo, Collection David H. Brolliet, Genève.

Photo: Fondation Fernet-Branca.

The second is Fally Sène Sow, whom I discovered before the 2016 Dakar biennale, at his home. I saw this young man creating sous-verre (under-glass paintings), and I understood the importance of sous-verre in Senegalese craftsmanship and history. I bought a work from him, and today, he is in major collections, like the Blachère Foundation. Had I been a speculative collector, I would have bought ten works from each of them to hold onto. But that’s not my mindset. I collect with my heart, not to speculate. I don’t criticize anyone—everyone has the right to own cultural assets and do as they please. For me, it’s about passion. When I fall in love with a piece, I can’t resist. I started collecting at 18 years old. It was, and still is, a passion.

Found objects

25,5 x 12,9 x 10,3 cm

© Romuald Hazoumè, Collection David H. Brolliet, Genève.

Found objects

31 x 23 x 23,5 cm

© Romuald Hazoumè, Collection David H. Brolliet, Genève.

Found objects

44 x 28 x 16 cm

© Romuald Hazoumè, Collection David H. Brolliet, Genève.

What role do you think collectors play in the art world?

In my view, a collector is a transmitter and an ambassador. I see myself as a cultural ambassador. I keep friendly, even familial, relationships with artists. I have funded catalogs and galleries to help certain artists develop and progress.

If you could meet one artist, dead or alive, to discuss their work, who would it be?

Among the living, I was lucky to meet Robert Indiana. Among the deceased, it would be Basquiat, because I was around him in New York but never met him personally. I encountered Warhol in nightlife circles, at Studio 54, but I never spoke with him either. At the time, I wasn’t really focused on art. It was much later that I acquired works by Basquiat and Warhol when an opportunity arose. They are among the few artists in my collection that I did not meet personally. They are artists of the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s. As for those who passed away in the ’90s or 2000s, I met them, exchanged ideas with them.

Going even further, my ultimate inspiration is Roy Lichtenstein. When I was 18, I couldn’t afford one of his works. When my father passed away, I could have bought a Lichtenstein, but instead, I chose to invest in young artists and support their careers. I could have purchased a Lichtenstein, hung it on the wall, and waited for its value to rise. But once again, I’m not a speculator—I don’t calculate that way. Perhaps a Lichtenstein would have yielded a huge profit, but the satisfaction, the pleasure of discovery, the moments spent in artists’ studios—that’s what I love.

Crystal, mixed media

H. 60 cm

© Pascale Marthine Tayou, Collection David H. Brolliet, Genève.

Photo © We Document Art.

You have more than 1,000 works in your collection. Is collecting an addiction?

Yes. It’s an addiction—a healthy one. It doesn’t destroy, but it can be dangerous if one falls into the trap of consumerism and uncontrolled buying. Many collectors buy compulsively, and some even go into debt to acquire artworks.

Is there a defining moment in your journey as a collector?

Yes. It was when I became publicly recognized as a collector. When I showcased my collection at the Fernet-Branca Foundation in 2018 in Saint-Louis, France. After that, the press approached me, and suddenly, they became interested in me.

Oil on metal

151 x 50 x 8 cm

© Mederic Turay, Collection David H. Brolliet, Genève.

“I want my collection to shine and spread in Africa”

What is your relationship with other collectors?

I keep regular relations with the collections of ADIAF and the Marcel Duchamp Prize. When I arrived in Paris, I had a 300 m² apartment. Parisians would welcome you at a hotel or a restaurant, never at their home. But I had 200 pieces in my place, and it was Open Bar and Open House. I even invited television crews to my home. Collectors were afraid of the tax authorities; they feared showing their collections. At the time, I was 20 years younger than the collectors I interacted with—I was the youngest, at 30 years old. I told them: “Show your collection.” And today, all collectors have books, catalogs, they showcase their collections, and they talk to the media. In Africa, I also realize that it’s not easy. People don’t easily open their doors. But I will open mine. I will organize receptions here and invite all my collector friends, whom I greatly appreciate, as well as my artist friends. In Geneva and Paris, I used to organize visits to my collection for museums and friends of museums. I am also developing the concept of museum patrons coming to see private collections.

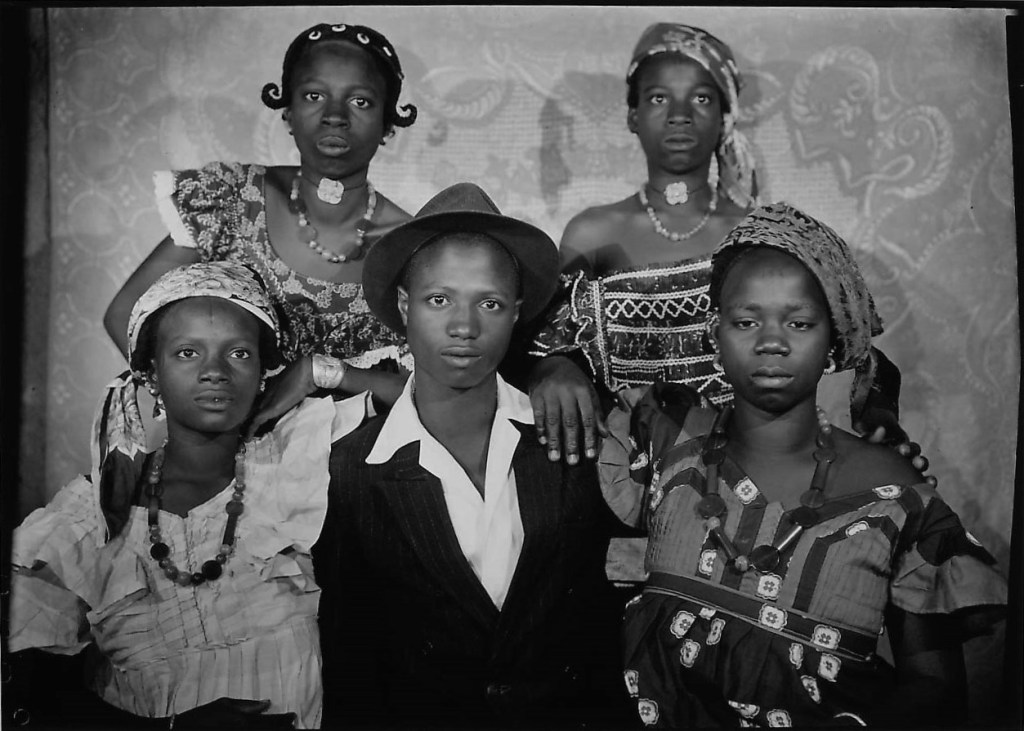

Silver print

18 x 13 cm

© Seydou Keïta, Collection David H. Brolliet, Genève.

Silver print

18 x 13 cm

© Seydou Keïta, Collection David H. Brolliet, Genève.

Silver print

13 x 18 cm

© Seydou Keïta, Collection David H. Brolliet, Genève.

Speaking of Africa, what motivated you to choose the continent for your collection?

I came to Senegal because I am passionate about contemporary African art. I discovered it through Romuald and Barthélémy. I chose to settle here and create a collection that will stay in Africa. It will never return to Europe. If I live, great; if I die, it will remain in Africa. I need to find a place that will become the home of the David Brolliet collection in Africa. I hope it will be Senegal. I was even offered to create a museum, but I don’t know yet. I am looking for solutions for this collection that I have built here. The rest of the collection, which is in New York, London, and Paris, is managed by notaries and experts, and we’ll see what happens. But the African collection is here. I decided to come to Senegal because I wanted an entry point into Africa. But I want this collection to shine and spread across the continent.

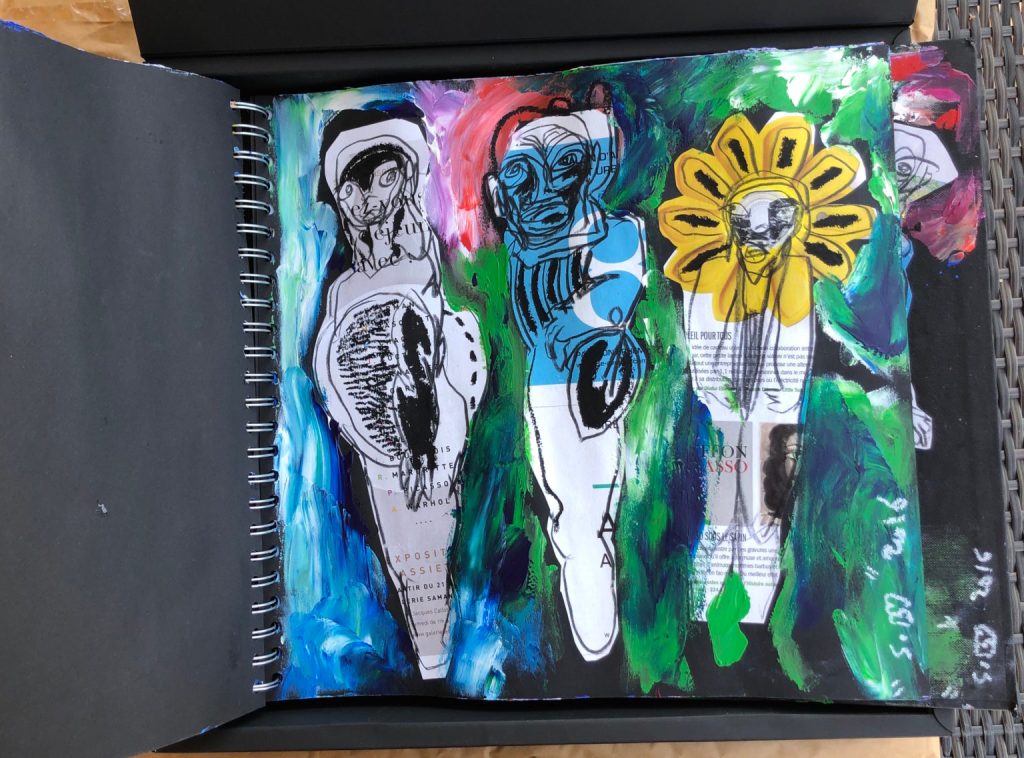

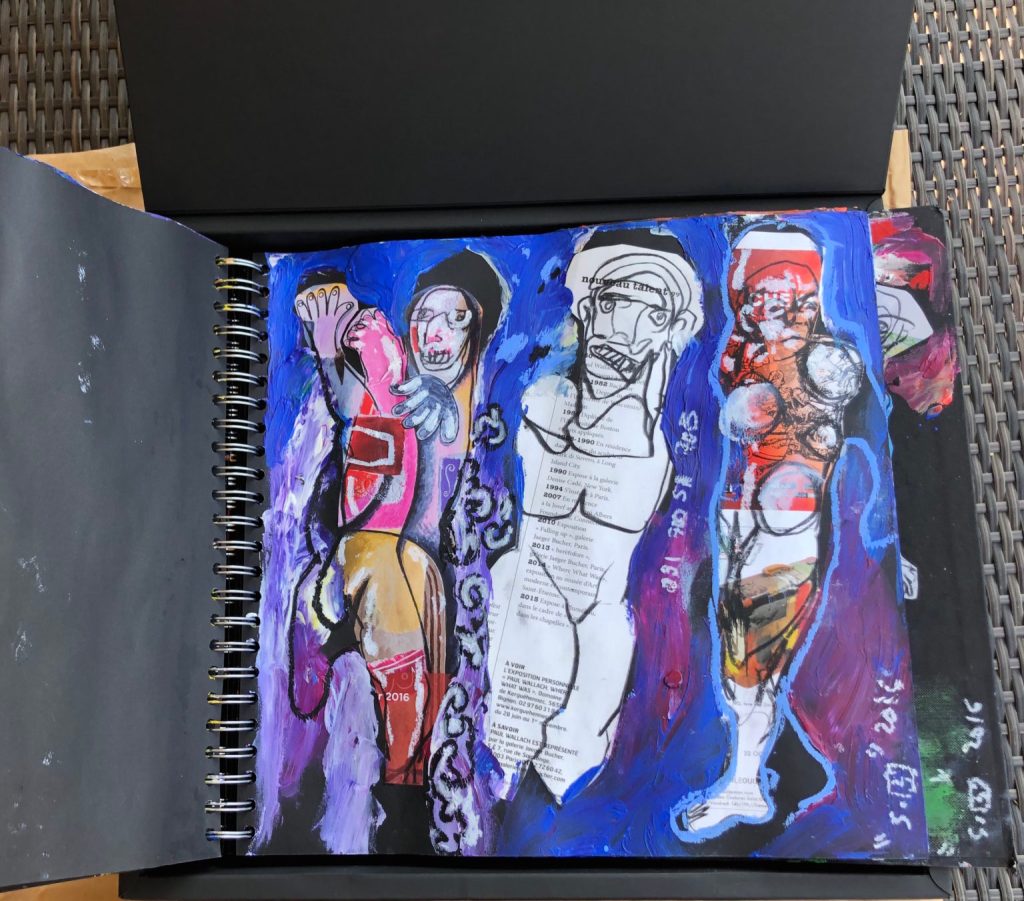

27 collages (acrylic and pastel on paper) in a portfolio

32 x 32 x 3 cm

© Soly Cisse, Collection David H. Brolliet, Genève.

I would be delighted if other Senegalese collectors joined me so we could put together a collective exhibition. I’m not trying to take all the credit. What drives me is the role of an ambassador, of sharing. I am here on a mission, and I must fulfill it. I came to be a bridge and a witness. Now that I am older, I understand that my role on this earth is to unite and open minds. I want to bring together artists and collectors. I am a Pan-Africanist who believes we must build things for the country, within the country. I want to create jobs in Dakar. I don’t want people to take boats and risk illegal migration. I want legal migration, with visas and proper documentation. That’s why I came. I want to create jobs, inspire cultural vocations, train museum mediators, and cultural journalists… It’s a mission. It’s patronage.

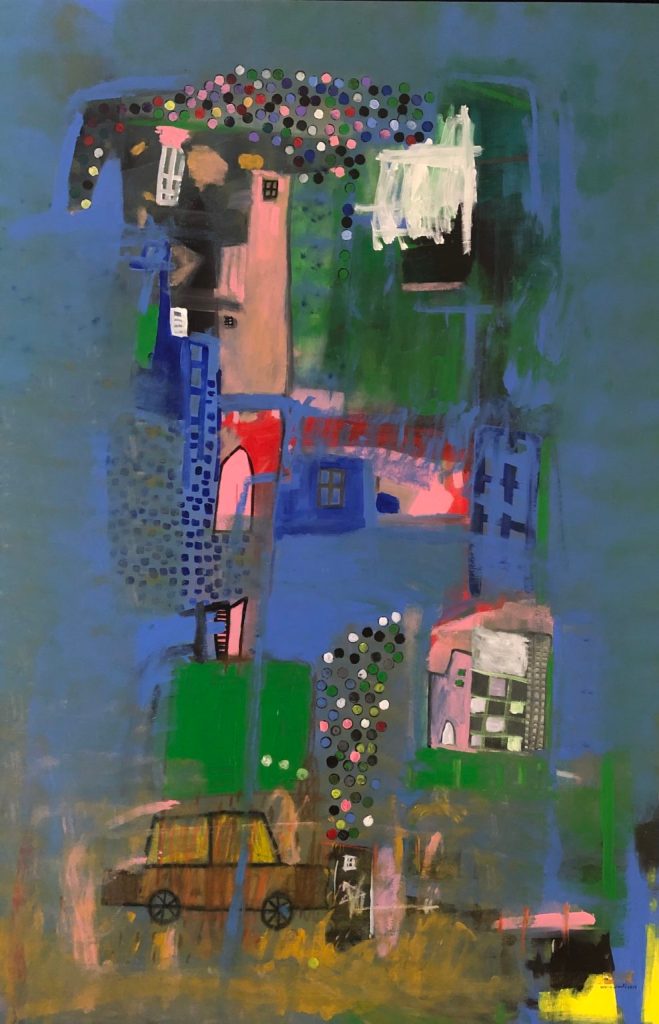

Paint and installation under glass (collage)

64 x 45 cm

© Fally Sène Sow, Collection David H. Brolliet, Genève et Dakar.

Paint and installation under glass (collage)

65 x 45 cm

© Fally Sène Sow, Collection David H. Brolliet, Genève et Dakar.

Why Senegal in particular?

Because of the talent here and the Dakar Biennale, which I discovered for the first time in 2016. There were a hundred private initiatives organizing OFF exhibitions. I had attended the Venice Biennale for years, as well as many others, but I was impressed by the enthusiasm and competence of the private sector in Senegal. The Dakar Biennale is the oldest in Africa—people tend to forget that. This year, I was proud that the great designer Ousmane Mbaye was involved. I have always said that design should be reintegrated into the Biennale because I consider it very important. And Senegal is not a small country. Leopold Sedar Senghor was Africa’s cultural figurehead of his time, and you can still feel it in every field. Omar Victor Diop created this year’s Lavazza calendar. Mohamed Mbougar Sarr won the Prix Goncourt. Koyo Kouoh founded Raw Material in Dakar. There are deep cultural roots here, brilliant people, intellectuals, and an incredible diaspora. Some told me, “Go to Côte d’Ivoire, to the Congo, or elsewhere,” but I chose Senegal, and I am very happy with my decision. I am sure that some of the artists in my collection will become major figures in the history of Africa and the world. I have a deep connection to Senegal, and I want this collection to stay here. If that’s not possible, I will look for another place in Africa.

What obstacles are preventing this project from happening?

When I met with the Ministers of Culture during Macky Sall’s presidency, they said: “This donation is interesting, but you’ll have to pay customs duties.” We are not on the same page. I am making a donation, and they are talking about customs fees. If I reach an agreement with the government, I intend to showcase contemporary art from around the world in Africa. I want to exhibit great photographers, painters, sculptors, videographers, and large-scale installations.

Acrylic on canvas

210 x 200 cm

© Slimen Elkamel, Collection David H. Brolliet, Genève.

At what stage is your project now?

To be honest, there is nothing concrete for now. I have been promised many things, but there is still a long way to go before they become reality.

Would your ambition be to create a contemporary art center?

I have been offered to set up an art center, a David Brolliet Museum, but I said no. My goal is to give back to Africa what I received when I was young. I believe that a collector must follow through with their approach, so I am ready to donate part of my collection under certain conditions.

Which conditions?

I can’t discuss them for now, as they are sensitive matters. Of course, my personal life does not matter. But beyond myself, I would like people to remember the collection and what I have done for contemporary African art. I would like the collection to travel across Africa, just as it has traveled around the world. Maybe it will become a foundation, but I haven’t resolved that question yet.

At this moment, you can’t give a precise date or the exact number of artworks you plan to bring to Africa, is that correct?

That’s correct, because since discussions are not progressing and we have no written agreement, I need to secure a formal document. Until I have that, nothing can be confirmed.

Acrylic, rabbal and wood

161,5 x 158,5 cm

© Viyé Diba, Collection David H. Brolliet, Genève.

On permanent loan to the MCN – Musée des Civilisations Noires in Dakar, Senegal

Photo © Pape Seydi

How do you plan to collaborate with local artists?

Collaboration starts with ongoing support. I follow artists, buy their works, and introduce them to international galleries. Thanks to my 45 years of experience in this field, I have had the opportunity to meet and interact with major figures in the art world and the most prestigious galleries. I also share my network with them. Africa has long been part of my collection through the artists I mentioned earlier. Africa is a deep need for me—to reconnect and to support African talents, to guide them. That is my choice. I have made significant acquisitions of iconic works. I am known for having a good eye, and I am respected for that.

What is your view on the local art market?

The market lacks proper valuation, except for a few exceptions. The reality is that international galleries buy at a low local price and resell at double or triple the amount. For example, African American artists are sold at much higher prices than artists in Africa, even though the talent is the same. Why should the same talent be priced ten times higher?

So there isn’t really a market. For Francophone African artists, language is a factor. English-speaking collectors support Nigerian and Ghanaian artists because they share the same language. English speakers often struggle with other languages, so they rarely take the leap. That’s why we need to support artists and help them export their work so that their value increases.

Acrylic and oil pastel on canvas

130 x 98 cm

© Mohamadou Ndoye, dit Ndoye Douts, Collection David H. Brolliet, Genève.

Acrylic and oil pastel on canvas

155 x 100 cm

© Mohamadou Ndoye, dit Ndoye Douts, Collection David H. Brolliet, Genève.

Chinese ink, acrylic and oil pastel on paper

65 x 50 cm

© Mohamadou Ndoye, dit Ndoye Douts, Collection David H. Brolliet, Genève.

To conclude, can you tell us about your recent acquisitions?

The latest one is in my living room. It’s a piece by Colette Diallo, a Senegalese artist I have known for quite some time. This artwork can be displayed in any orientation. I also recently acquired a piece by Khalifa Ababacar Dieng. My collection includes works by Douts Ndoye, Viyé Diba, El Sy, Arébénor Bassène, and many others.

Read also:

The Evolution of Contemporary Art in Senegal: A Conversation with Bara Diokhané

The World of Senegalese Contemporary Art Through Sylvain Sankalé’s Eyes

The State of Contemporary African Art Today: Dr. Ibou Diop’s Critical Perspective

Why Dakar Stands Out in the World of Art! A Conversation with Wagane Gueye

Leave a comment