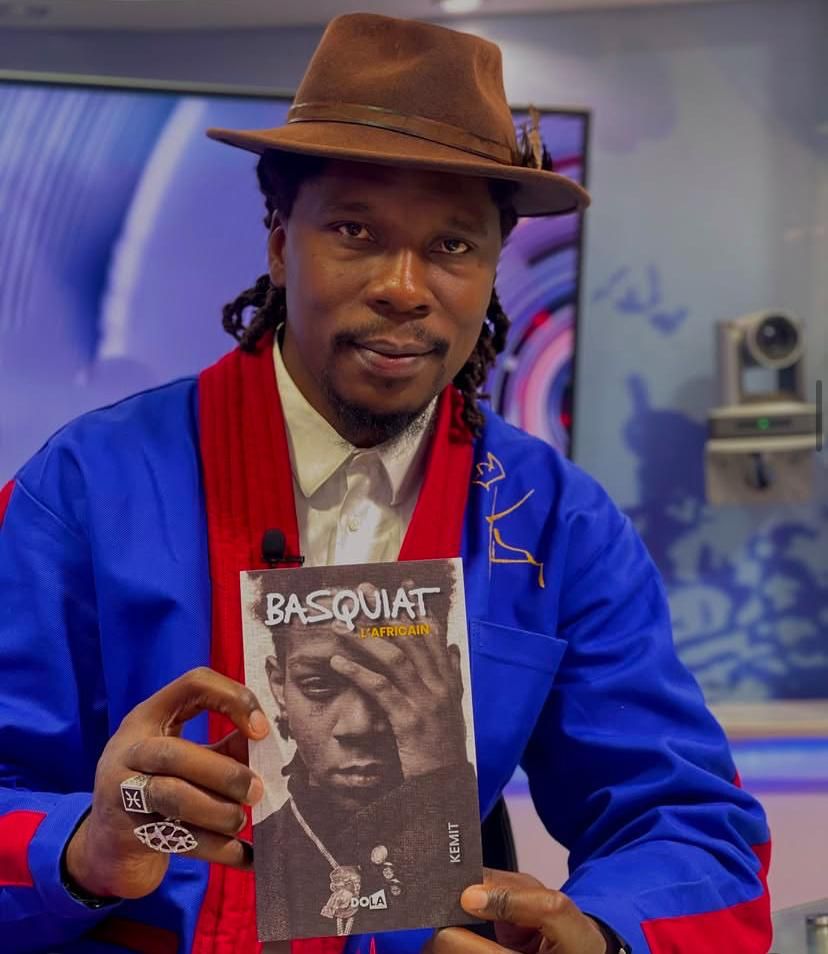

Published in 2024 by Dola Editions, Basquiat l’Africain (Basquiat The African) is written by Kemit, a Gabonese artist whose real name is Franck Mboumba. A multifaceted creator—author, composer, singer, rapper, and poet—Kemit explores the African roots that influenced Jean-Michel Basquiat’s art, offering a fresh perspective on the personal and cultural forces behind his work. A towering figure in contemporary art, Basquiat revolutionized painting with his raw, expressive style and profound social commentary, leaving an indelible mark on the global art scene. In this interview, Kemit shares not only an analysis of Basquiat’s engagement with African spirituality but also his own journey of reconnecting with his heritage. With a thoughtful and personal tone, Kemit reflects on how these encounters with African culture helped redefine Basquiat’s identity. His narrative invites readers to view art as a deeply human dialogue that bridges personal history, cultural pride, and creative expression.

In your book, you place a particular emphasis on the African aspect of Jean-Michel Basquiat’s identity. What are the most striking African influences in his work, and how did you explore them in your book?

I believe that Basquiat drew nourishment from everything he could find in African culture, particularly African spirituality. There’s a section in the book dedicated to voodoo. He discovered Haitian voodoo, which has its roots in Benin, West Africa. So, I think what attracted him to the elements linked to African identity was also the search for the unknown—those aspects he initially did not know. He came to understand them through the research he conducted and the opportunities he had to meet people, notably during his trip to Côte d’Ivoire in 1986.

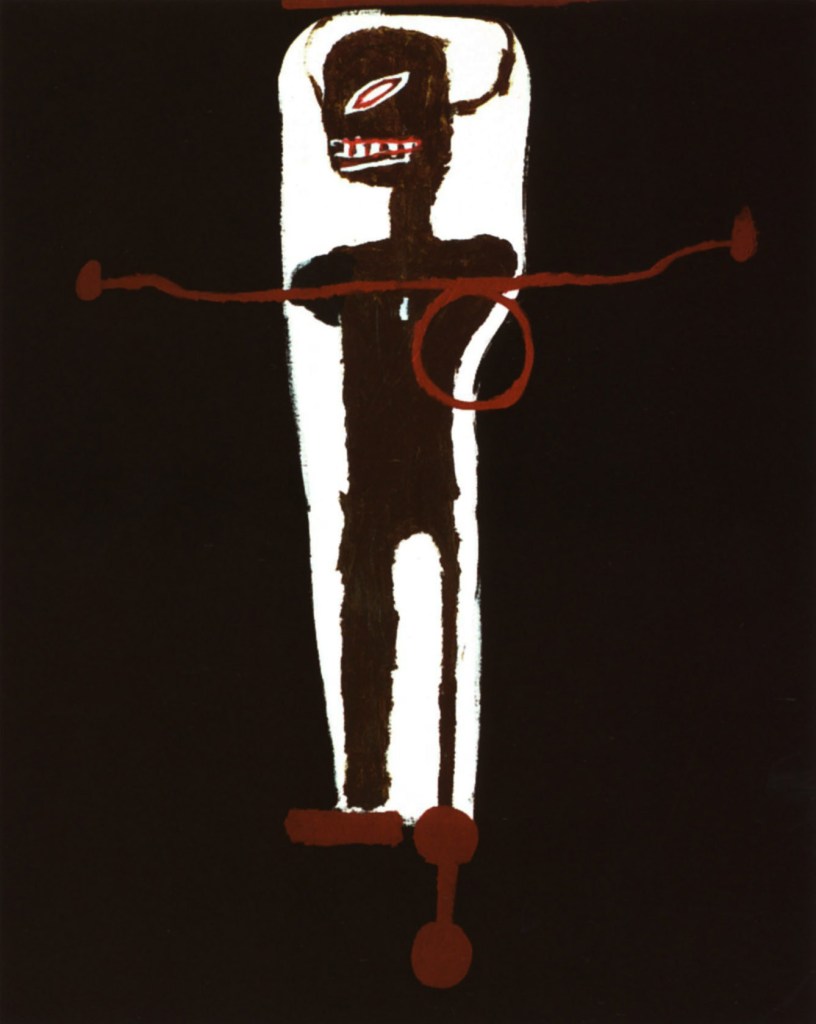

Basquiat often used symbols, masks, and elements related to voodoo in his creations. How do you interpret these symbols in the context of his Afro-American identity, and how did you approach this aspect in your book?

Many African-Americans feel the need to know where they come from. They want to reclaim that part of their identity. I titled the book Basquiat the African because I think his Africanity is not distant. His Africanity is close, especially since his father was Haitian. Black people in Haiti are descendants of slaves deported from Africa. They populated that territory. They continued to practice African spirituality, namely voodoo. That’s why I speak of Basquiat’s voodoo as Haitian voodoo. It is through his African identity—his father’s roots—that he came to know voodoo. It is also through his Afro-American mother. She is Puerto Rican. Afro-Puerto Ricans originally came from Nigeria. Puerto Ricans are people who were deported from Nigeria during slavery.

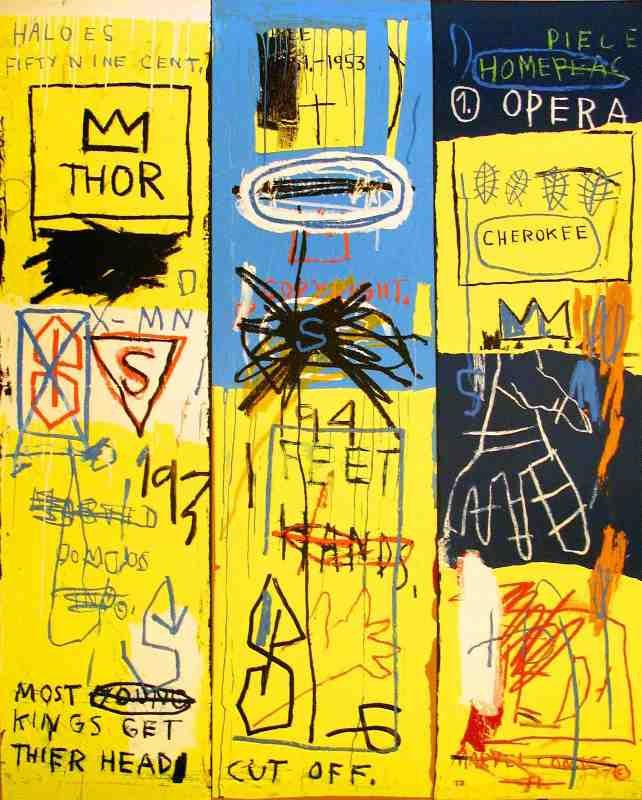

On page 140, you write: “his work is an act of reclaiming history, a way of giving a voice to those who have been silenced. This is a form of engaged art.”

In fact, his art became engaged out of necessity. He suffered a lot of marginalization. At times, he was even relegated to the status of an “African artist.” He took this very badly because it implied he was an inferior artist. I quoted him in the book when he said, “I am not a black artist; I am an artist.” Simply because seeing him at the level he had reached was not favorable to many people. They questioned the quality of his art. They tried to claim that it wasn’t really art, and that it was merely exotic art. They acted as if his art were of less value than what others did. However, it was just as authentic. The reclaiming came later. He realized that in his personal history as a black artist, he was missing symbols. Important figures were absent. It wasn’t that these figures did not exist in his art, but that they were not valued. That’s why, at a certain point, he painted with a dynamic of engagement and of valorizing everything he was. This is why he painted famous black figures like Muhammad Ali, great jazz singers, and all those important black personalities of his era—to put black identity back at the center of the debate. It was to say that while we were once slaves, that is not all we are. Today, we are people who achieve important things, and that must be recognized.

“Basquiat’s Art is a journey into African Art”

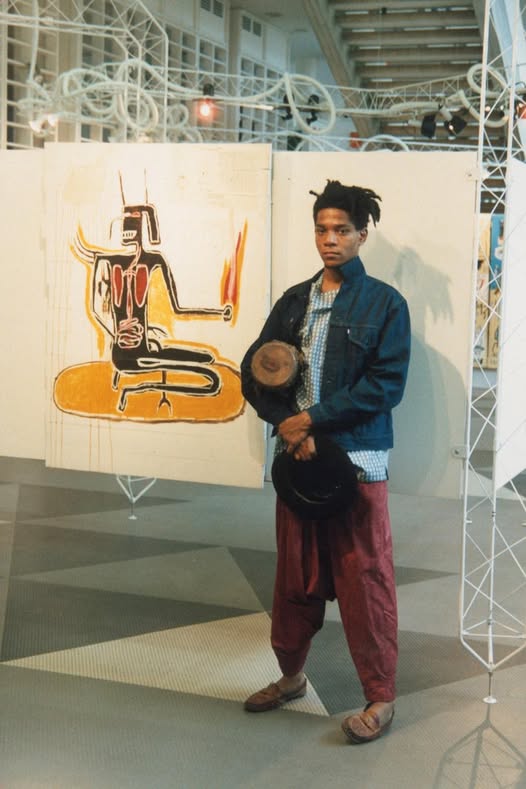

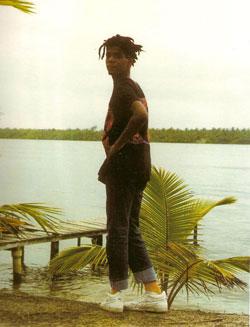

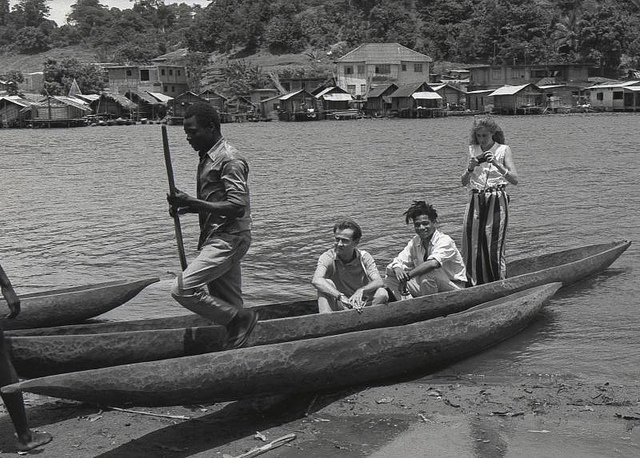

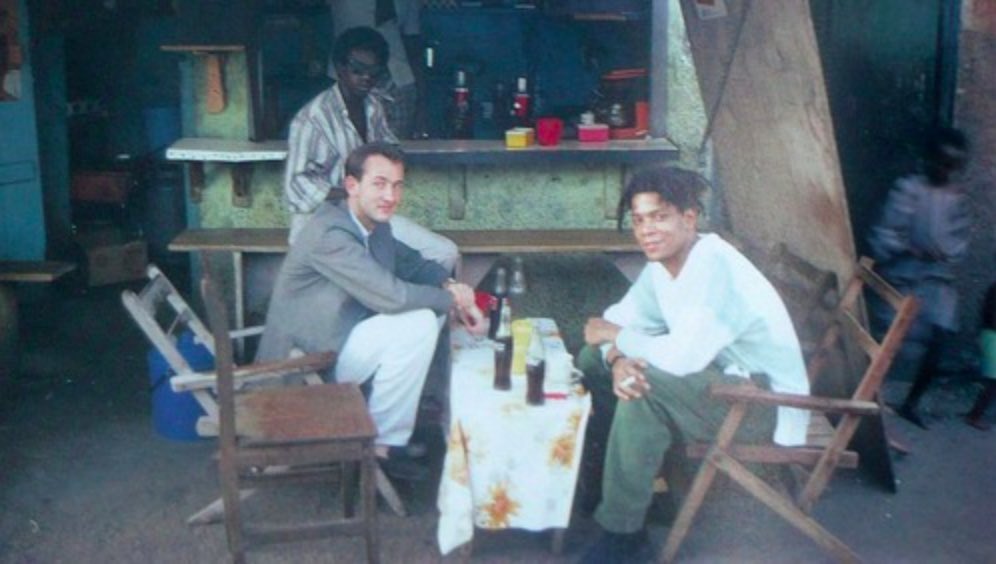

You mention Basquiat’s stay in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, for his first and last exhibition in Africa, in 1986. In your opinion, how did this direct connection with the African continent shape his journey?

The trip to Abidjan is important because it allowed him to visualize and experience a space he had often only perceived from afar through books and television. But in Côte d’Ivoire, he found himself on the territory of his deep origins. He was in Africa. This was significant for someone who was often reminded of his African roots. He realized that Africa was not what he had been sold. You know, there are still some countries where people think that Africa is a single country or that Africans live in the trees—such absurd ideas. But in Côte d’Ivoire, he noticed very talented artists, communities living in an organized way, and so many things happening. He saw Africa from a different perspective and, above all, managed to capture the spirit of the people.

In Korhogo (in northern Côte d’Ivoire), when he arrived, there were children singing around him. This is something that happens almost everywhere in Africa when a stranger comes to a village—children are happy and start singing. It’s a natural act of kindness, something he wasn’t used to because he came from a hyper-violent New York society. Ultimately, he discovered a welcoming Africa, different from what he had been told. Another important aspect of this journey is that it was the only time he wasn’t confronted with drugs. He was free from all the New York pressure and far removed from showbiz. In Côte d’Ivoire, he discovered the charm of simple things. It reminded him that his life didn’t have to be one of constant conflict. It could be something else. It could be peaceful and lived differently. The problem was that when he returned to New York, he fell back into the society in which he had grown up—a society that had influenced his entire life. Ten days in Africa are not enough to change 26 years of life.

Your book is not only a tribute to Basquiat but also a reflection on how the artist redefined contemporary art. What lessons can today’s African artists draw from his artistic legacy?

The lesson for today’s African artists is that you don’t have to borrow from elsewhere to make an impact or excel. You can be true to what lies deep within you—who you really are, your culture, and your identity. Basquiat’s art is a journey into African art. It’s full of symbols that we Africans sometimes overlook because we want to look like others.

Could you tell us what led you to become interested in Basquiat?

What interested me about Basquiat was his artistic journey. He was first and foremost a self-taught artist. He broke the rules in a society that was already set up. People who excelled in this field typically went through conventional routes like art schools. He didn’t attend any school; he came from nothing, from the streets, from the underground—much like the story of rap. I find it beautiful to think that one can start from nothing. It’s wonderful to remain authentic and be oneself. You can redefine the norms of the environment in which you live. Basquiat is the greatest black artist in the realm of painting. In literature, we have renowned figures like James Baldwin, Aimé Césaire, and Senghor. We have great athletes in sports. In music, we have Ray Charles and James Brown. But in painting, it’s Basquiat. So when you have an artist of such stature, he must be known. In reality, I wrote this book so that the black community could truly know Basquiat. He was an activist for black people, but Paradoxically, the Westerners know Basquiat more. They own Basquiat’s paintings because they have the purchasing power.

How has your own vision of African culture and spirituality influenced your approach to writing this book about Basquiat?

Basquiat reconciled me with my African roots. He showed me that we must value our culture. I grew up listening to the music of the ’90s and 2000s. This entire generation is almost entirely influenced by American hip hop. That’s fine, but there are also creations that have come from our own continent. When we talk about African music, we often forget that there are artists who have made a global impact. Michael Jackson was inspired by Manu Dibango. If Michael Jackson took an interest in Dibango’s music, it means there is something there. The same goes for Shakira’s “Waka Waka” during the 2010 World Cup in South Africa, which was inspired by traditional African music. There are treasures in our culture that we must value. If we don’t, we will continue to complain that someone else has appropriated our music. If we don’t want others to appropriate our heritage, it is up to us to valorize it.

As an author, slam artist, and poet, is there a quote from Basquiat that touches you particularly and that you would like to share with us?

It’s the one I put on the back cover of my book, where he says, “Picasso arrived at primitive art in order to give of its nobility to Western art. And I arrived at Picasso to give his nobility to the art called ‘primitive.” This phrase was the catalyst for writing this book. I found it both profound and powerful.

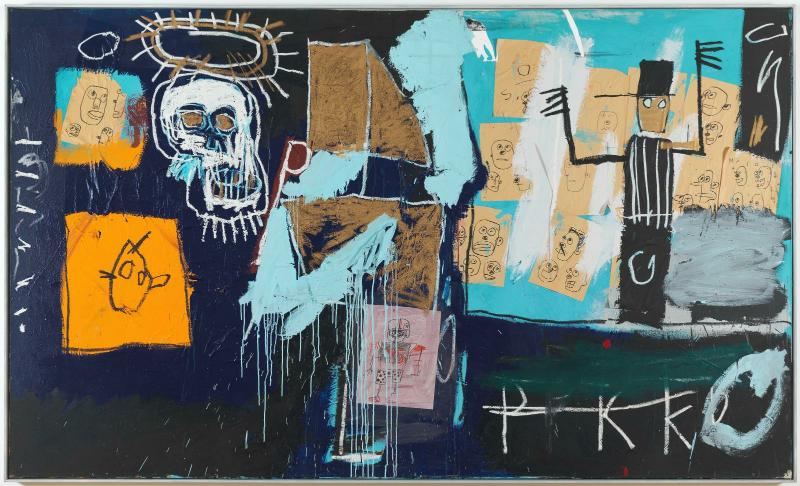

Is there a painting in his career that you find the most striking and that spoke to you?

It’s the work Untitled (Skull), 1981—the one that was valued over 110 million dollars. When I look at that painting, I see many things that people do not perceive.

And if you could imagine a meeting between Basquiat and a contemporary African artist, who would it be, and how do you think they would interact around art?

It would be me—and we would make a music album together, with him designing the album cover. I would love to work with Basquiat. We would compose music together.

Read also

Saadio: The « Senegalese Basquiat » Shaping African Pop Art

From Geneva to Dakar: David Brolliet, a Collector of Art and Encounters

Leave a comment