Ousmane Ndiaye Dago is a Senegalese artist whose unique journey blends various forms of artistic expression, ranging from graphic design to photography and painting. Through his art, Dago explores the invisible and abstract dimensions of the human body. In this article, we invite you to discover the world of Ousmane Dago, an artist whose ever-evolving work engages the past and present, the local and the global, offering a unique vision of contemporary art.

Born in 1951, Ousmane Ndiaye Dago is a versatile artist: graphic designer, painter, designer, and photographer. He graduated from the School of Fine Arts in Dakar in 1976 and pursued graphic design studies at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp, Belgium.

From Photography to Painting: An Artistic Hybridization

Photography emerged for Ousmane Ndiaye Dago as an alternative to painting, a field that requires time and resources. He knew that many Senegalese viewed photography as having a low status as art. So, he sought to give it a pictorial dimension.

“You can’t exhibit in graphic art. So I thought about exhibiting in painting, but it would take too much time. I decided to exhibit photography. But in Senegal, people think anyone can do it. So I tried to make my photos look like paintings to make them more accepted,” he explains.

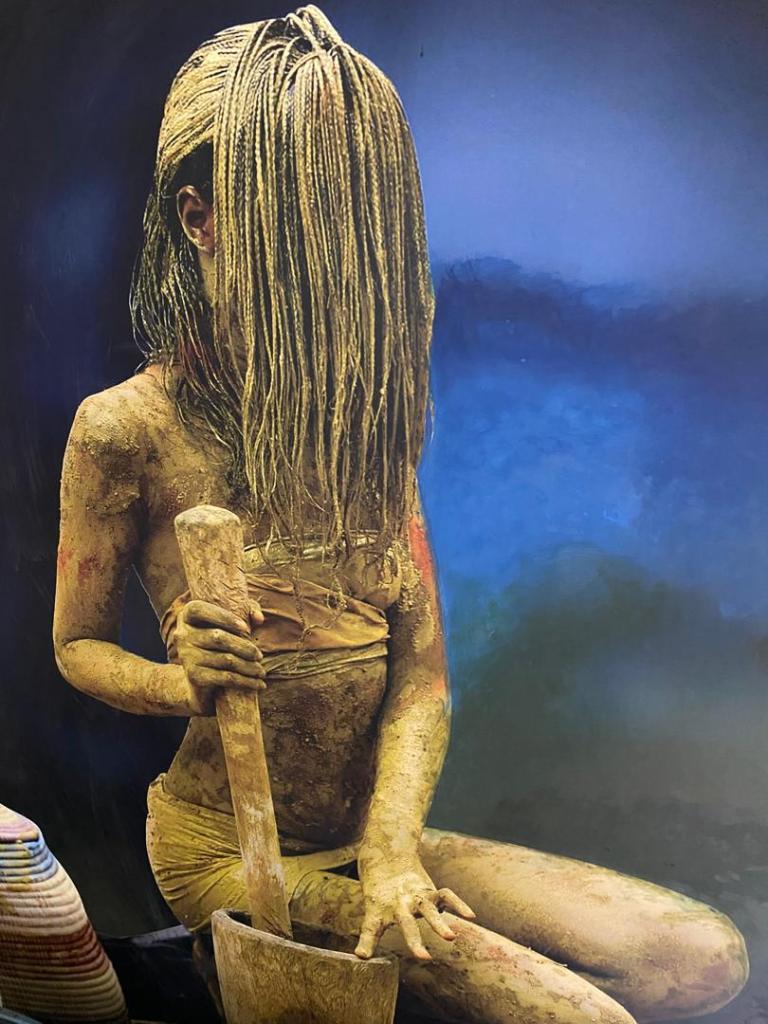

Inspired by a reflection on the invisible, he developed a unique aesthetic approach. It is much like the wind that is perceived without being seen. His photographs of human bodies are covered in earth, hair, wig or locks. This conceals the identities of the models. “It was important to mask the face and skin so that the body wouldn’t be identifiable. This enhances abstraction and also bypasses certain cultural reservations.”

Sometimes, chance reveals unexpected paths. While working with materials such as clay, Ousmane Ndiaye Dago noticed that his photographs took on a sculptural dimension. His series “Femme Terre” is a beautiful illustration of this: the body is sublimated by natural pigments like charcoal and clay, giving his works a nearly tactile depth.

A Critical Look at Identity and Culture

His work is strongly influenced by Senegalese culture and environment. He draws inspiration from daily life and aims to highlight local cultural elements in his art. In his series Sénégal ben bopp la, ken monuko xar ñaar (Senegal has a head, no one can divide it into two), he portrays a woman wearing various cultural garments representing different ethnic groups of the country, blending photography and painting to convey his message of national unity.

“I take a girl, I rent cultural clothes to symbolize different ethnic groups, I take photos, and then I paint on them. It’s a thoughtful process.”

This hybrid approach between photography and painting gives his work a quasi-mythological dimension, where identity becomes both multiple and universal. Dago erases distinct features and layers cultural symbols. Through this process, he questions how we perceive the individual. He also challenges how we see the community in a changing society.

Art as an Act of Creation and Sharing

For Ousmane Ndiaye Dago, being an artist is about creation. “The greatest artist is God, the creator,” he affirms. Inspired by his environment, he wishes for his work to be appreciated first and foremost by his fellow countrymen. His commitment is particularly clear in his approach to portraiture. He invites his fellow Senegalese to entrust him with images of their loved ones. He then elevates these images through his art.

Ousmane Dago does not confine himself to an exclusively aesthetic approach. He deeply reflects on the impact of images. He also considers their meanings. He sees art as a way of sharing and cultural engagement.

The importance of cultural context is essential in his view. His critical perspective on graphic design in Senegal underscores this necessity. He cites the example of the senegalese public health logo. It shows a snake and a heart—a symbol that, in the local culture, evokes love or sorrow rather than illness. “In our culture, we say ‘my body doesn’t feel well,’ not ‘my heart doesn’t feel well’ when talking about health,” he explains.

Exhibitions

His work has been showcased in prestigious venues such as the Museo Communale in Genoa, the Fundació Vila Casas in Barcelona, and Sho Contemporary Art in Tokyo. He has also participated in several editions of Dak’Art, the Dakar Biennale of Contemporary Art, and international events like the Bamako African Photography Biennale and the Biennal of Grafic Arts of Brno. Ousmane Ndiaye Dago has also designed logos for many public institutions and companies in Senegal.

Today, he continues to experiment with new combinations of photography, painting, and digital techniques, constantly refining his approach to offer a fresh perspective on the representation of the body and identity. Through his ability to merge media and challenge perceptions, Ousmane Dago has established himself as a major figure in the contemporary art scene, offering a unique vision where the visible and invisible converge into a striking aesthetic. The artist’s project is to create a school to train future generations of graphic designers.

Interview

My name is Ousmane Ndiagne Dago. I studied at the School of Fine Arts in Dakar from 1973 to 1976. After earning my diploma, I received a Belgian scholarship to study graphic arts, specializing in publishing. In the 1980s, I returned to Senegal to work in publishing houses, particularly at Nouvelles Éditions Africaines. I worked on book illustrations, layouts, design, logos, brochures, and leaflets. At one point in my life, I wanted to do an exhibition of my work. However, graphic art is not something you can show. So, I considered exhibiting paintings, but that would take time. I then decided to exhibit photography instead. However, selling photographs was difficult because Senegalese people did not consider photography as an art form. They believed that anyone could take a photograph. So, I decided to create photos that would resemble paintings to encourage Senegalese people to buy artworks. At first, I thought about nature as a topic. Later on, I decided to focus on the human body. However, culturally, the body was not widely accepted. So, I thought of working in the spirit of the wind—something that exists but is invisible. I decided to photograph the body but cover it with earth, so people would never know whose body it was. I also concealed the faces with hair, dreadlocks, so the face would be hidden—no face, no skin. It became abstract.

When I finished, I showed it to people, and they instantly recognized it as art. This led to various exhibitions, including the Venice Biennial in 2000. Some of my works are displayed in the Naples metro. In 2003, I participated in the Havana Biennale and later the Valencia Biennale. I also worked with Porsche in Milan on a project titled The Body and the Engine. I have exhibited extensively in Italian galleries. Now, I continue my work, combining the impression of painting, digital tools, and photography—I merge these three elements.

Some of your works give an impression of sculpture? Is that intentional?

Sometimes, accidents lead to unexpected results. When I applied earth and clay on my characters, I achieved sculptural effects. I never intended to come to that result, but I loved the sculptural feel that emerged from my work. My work has been well received in Italy. I believe this is because it evokes the spirit of the Renaissance. In my Femme Terre (Earth Woman) series, I use clay as a base. Then, I add natural colors, charcoal…

What does it mean to be an artist, to you?

The greatest artist is God, the Creator. Someone who has never attended school is self-taught, but that does not mean they are less talented. An artist is someone who creates something. If you do not create, you are not an artist. Creation is influenced by one’s environment.

You have spent time abroad. How has that environment influenced your work?

I learned technical skills in Europe, but my creative process is deeply rooted in my culture. I first want my own culture to appreciate my work. Many artists create installations that are well received in Europe. But, in Senegal, such work might not be recognized as art. Some artists create to please a European audience. I focus on making my work resonate with people here in Senegal. I often ask people to give me photos of their loved ones, which I then rework with paint. I sell them at affordable prices. It makes me happy to know that my retouched photos are displayed in the homes of my fellow citizens.

What are your artistic themes?

My background in graphic design trained me to create for others. When designing a logo, for example, the goal is to satisfy the client. But as a painter or sculptor, you create what you feel, and others may or may not appreciate it. So, women are my primary topic. At art academies, models are often women. In my work, everyone embodies womanhood in some way.

Can you tell us about your creative process?

When I have an idea, I think about it, take my camera, and create the image. For example, in my series Sénégal Benn Bopp la, Kenn Monuko Xar Ñaar (Senegal Has One Head; No One Can Split It in Two), I wanted to create a symbolic image. I photographed a woman dressed in traditional outfits representing different ethnic groups. I took the pictures and then applied paint. This was a well-thought-out project.

Sometimes, I take spontaneous photos when something interesting catches my eye. Still, that is rare. Most of the time, I conceptualize my projects before executing them. I aim to share beauty because, ultimately, art is about sharing. I carefully consider what resonates with my environment and aligns with my culture. For example, I often critique logos in Senegal because they lack cultural relevance. The health sector logo here features a heart with a snake. But in our culture, the heart does not symbolize illness. The heart means love or sorrow. A woman will say, “My heart is unwell because I haven’t seen my son in years.” This does not mean she is physically sick. When we are sick, we say, “My body is not well.” Cultural context is crucial in design. Ignoring it means missing the mark entirely.

Leave a comment