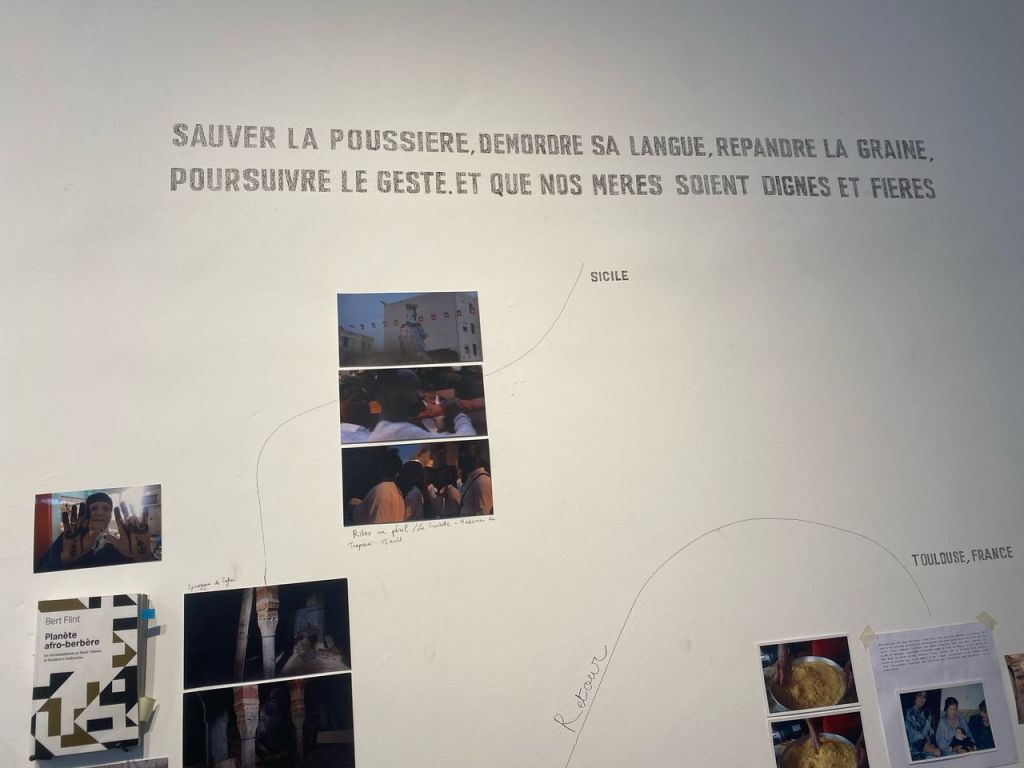

“For a Counter-Mapping of Resistance Practices (Art, Ritual, and Politics)” is the culmination of Camille Lévy-Sarfati’s research residency at Gallery Selebe Yoon in Dakar. This installation is both an artistic and intellectual exploration, offering an alternative cartography of resistance practices, where art, ritual, and politics intersect. By assembling texts, images, and objects, the installation creates a dynamic space of reflection, inviting visitors to engage with histories of displacement, resilience, and transformation. A writer and curator based in Tunisia, Camille Lévy-Sarfati conceives this counter-mapping not only as a reinterpretation of territories and memories but also as a counter-narrative against forms of domination and erasure. Her research and curatorial work are rooted in encounters with artists from diverse backgrounds—from Tunisia to Senegal, as well as Palestine and South Africa. In this interview with DakArtNews, she discusses her journey, inspirations, and the connections she weaves between artistic practices and resistance dynamics across different geographies.

Can you tell us more about the origins of your research, For a Counter-Mapping of Resistance Practices? What inspired you to explore this project?

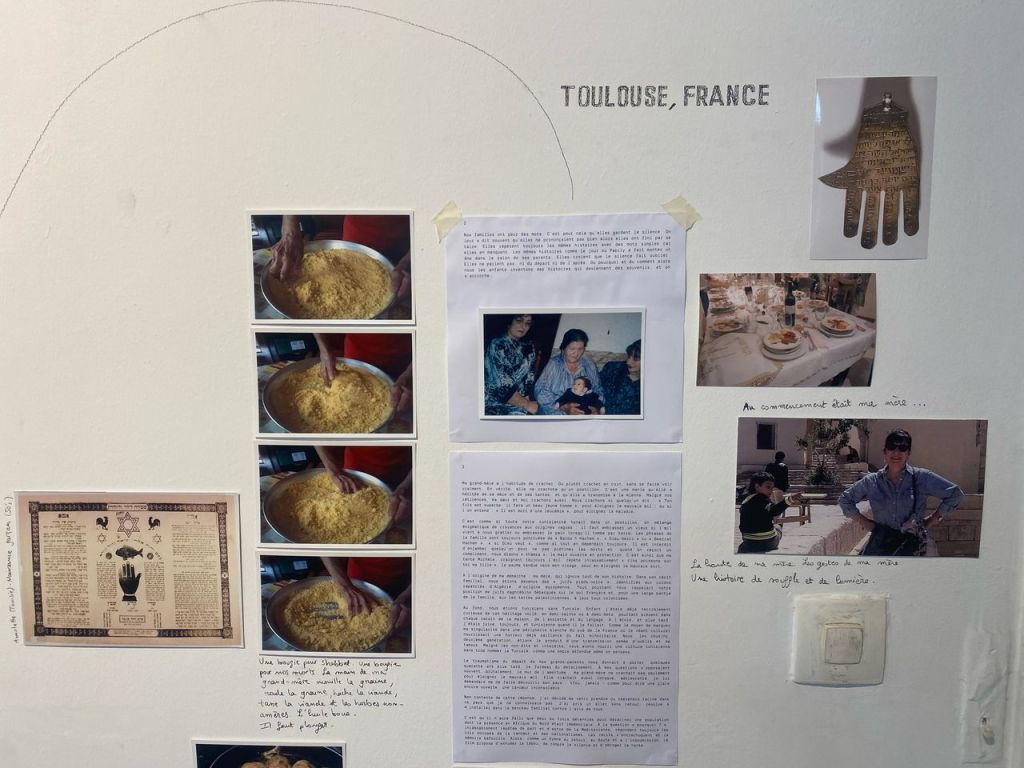

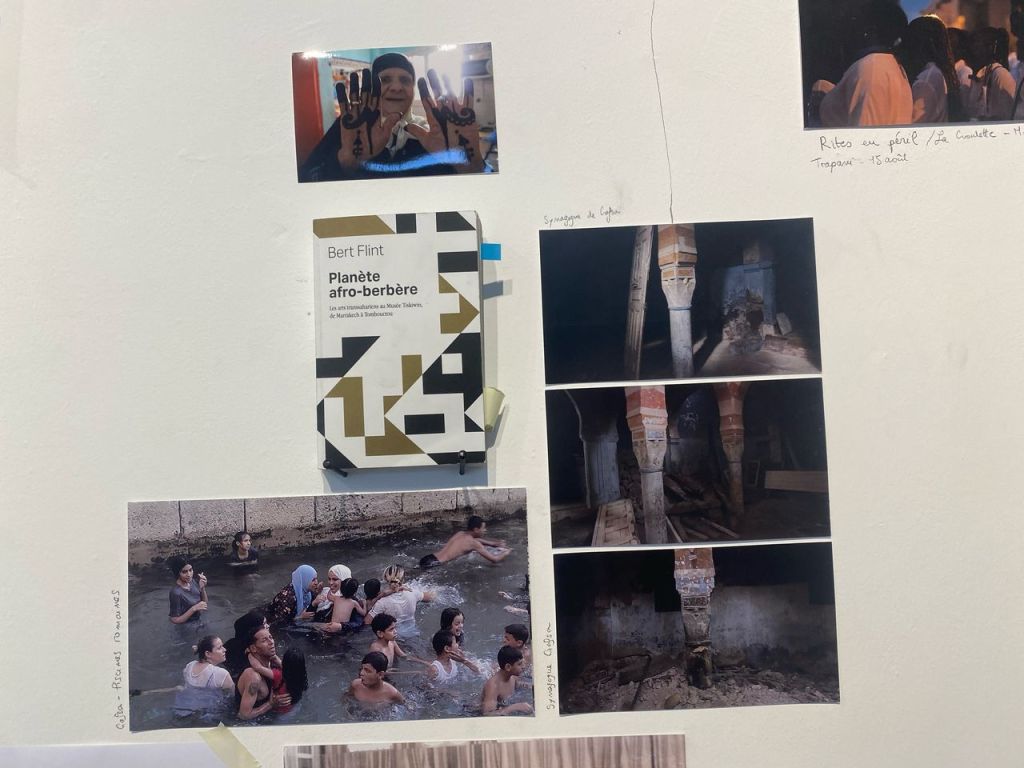

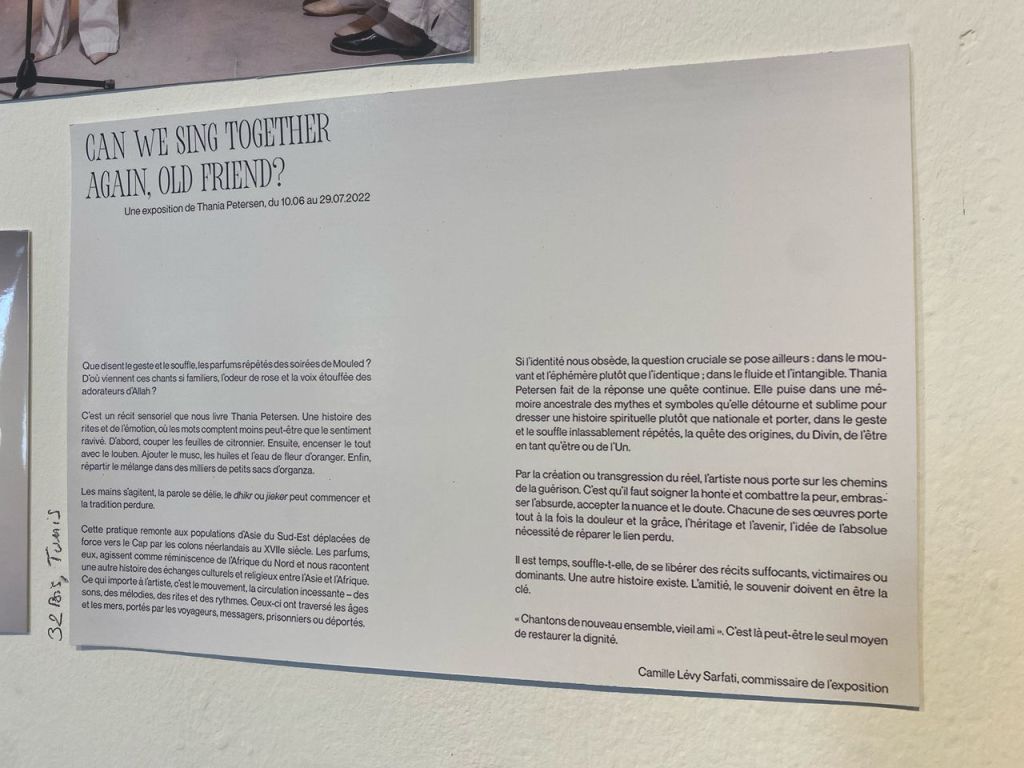

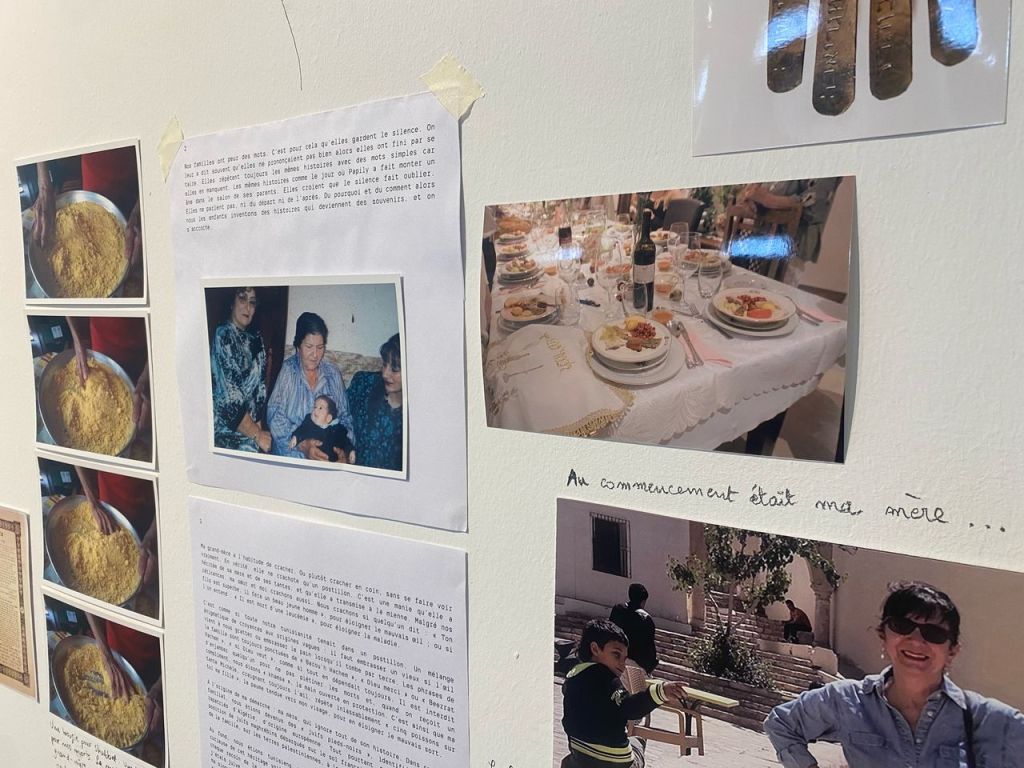

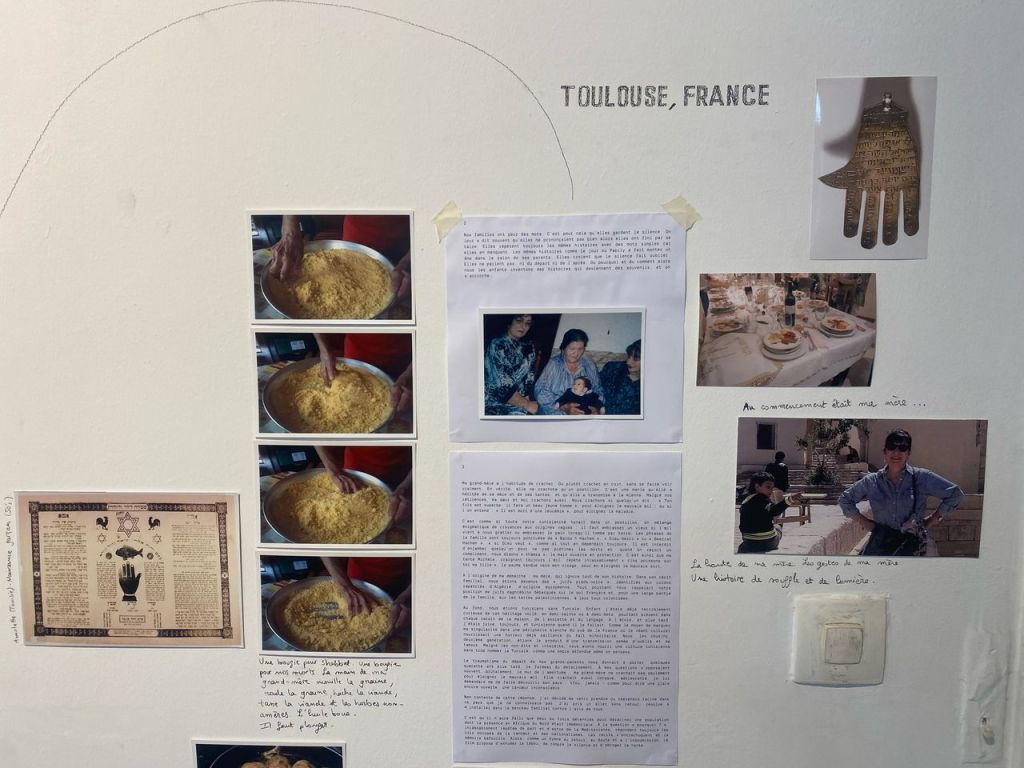

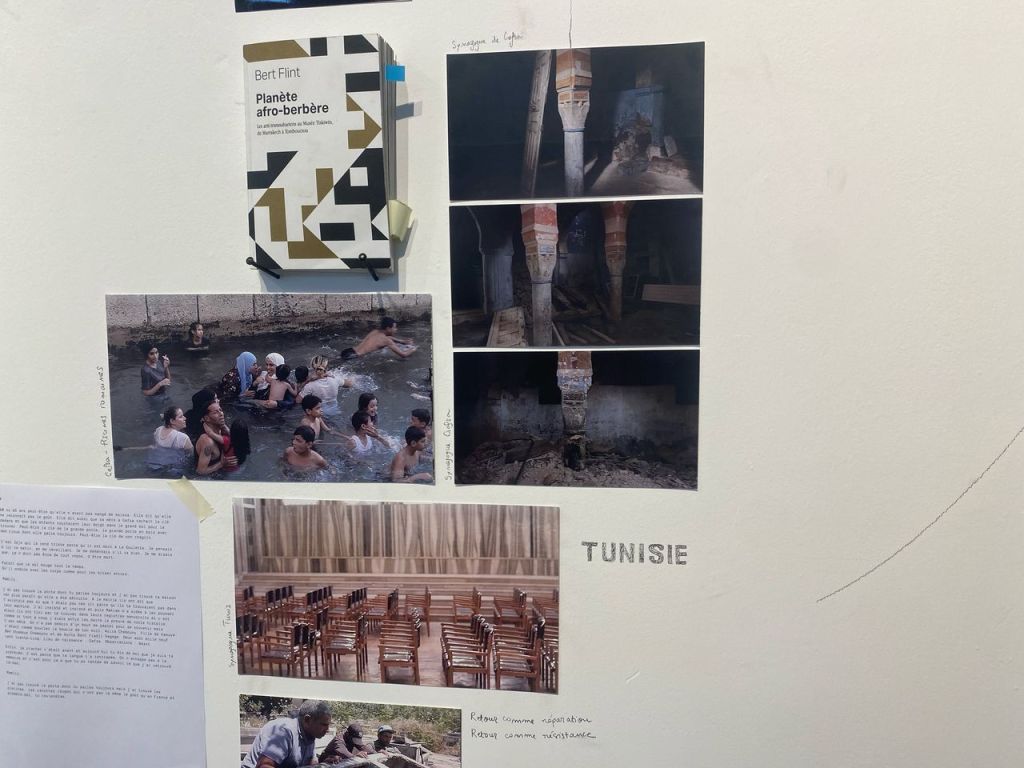

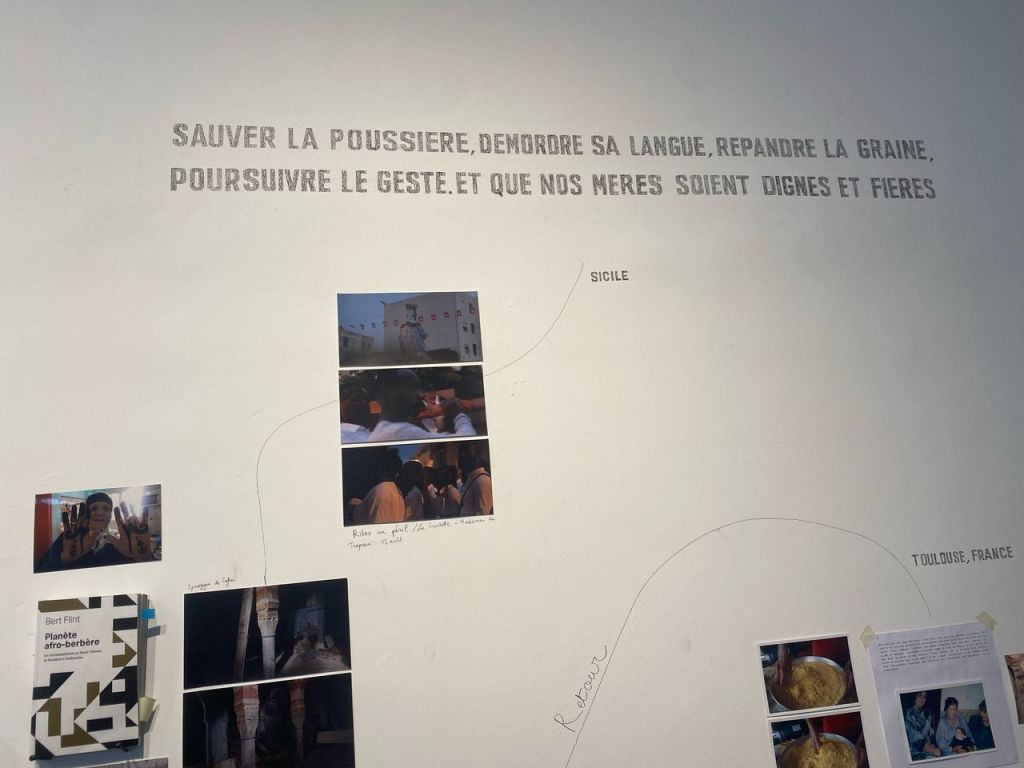

My research stems from a deeply personal experience—a choice to return. My family left Tunisia after independence, but I decided to return a few years ago, seeing this return as an act of resistance and reparation in response to nationalism and the effects of both colonization and Zionism, which caused the displacement and uprooting of Tunisia’s Jewish population. Everything starts from there, from my return to Tunisia. I wanted to work with a constellation of artists, researchers, and activists on the question of ritual and its interactions with artistic practices and the political sphere. That is, how artists can take rituals and transform, translate, or subvert them—sometimes turning them into spaces of survival, resistance, or political struggle.

How would you define the interaction between ritual practices, art, and politics in your work? What specific connections have you identified?

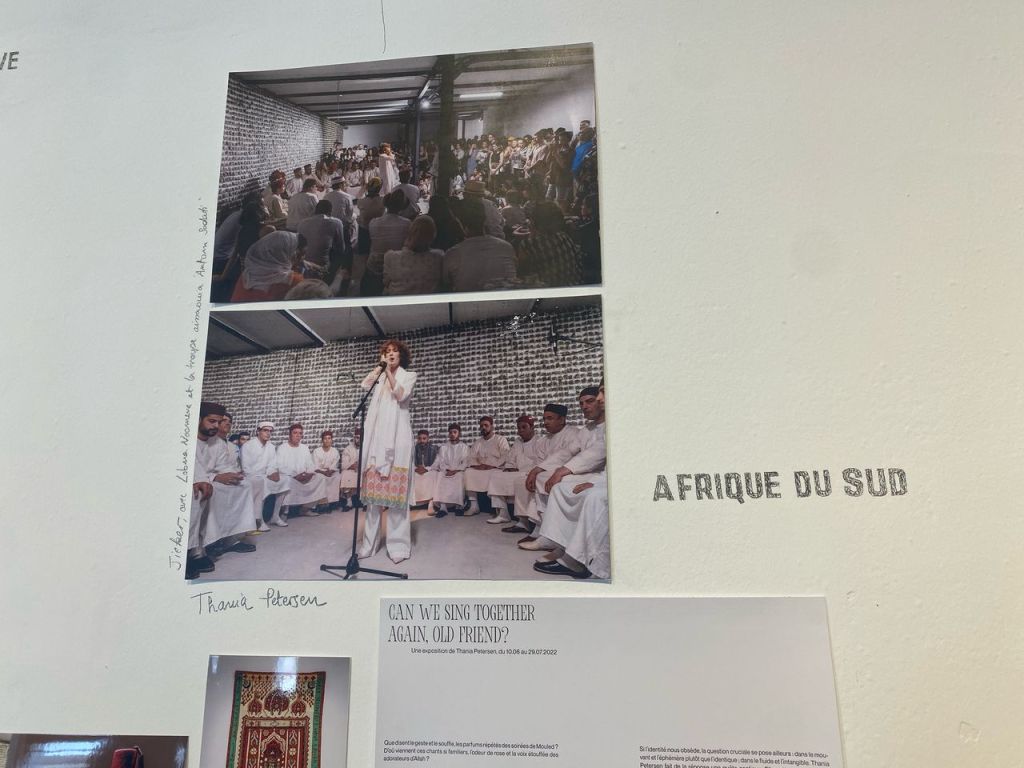

As a curator, my work revolves around linking artists who engage with these ritual spaces through cinema, literature, and visual arts. But it also extends beyond official art spaces—into public, domestic, and sacred spaces. My curatorial practice seeks to create connections across different geographies, forging shared rituals. It is not the ritual itself that interests me, but what artists do with it—how they reinterpret and reappropriate it.

Were there any unexpected discoveries during your encounters with the artists?

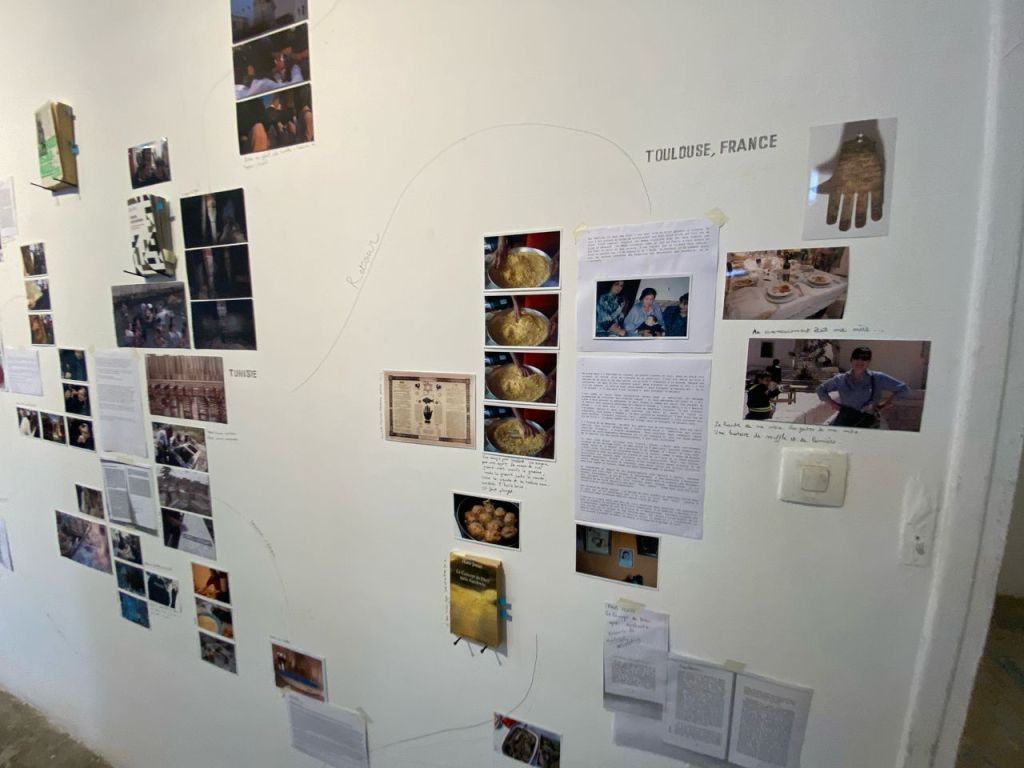

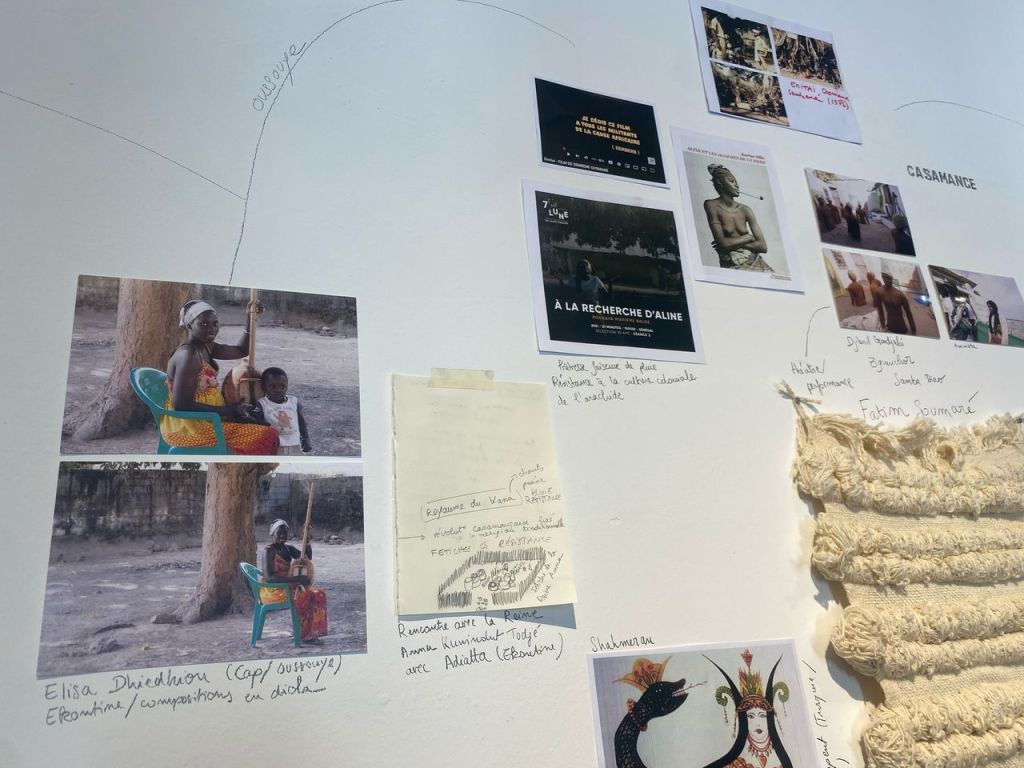

The places represented in this counter-mapping are those I have traversed physically—places where I have spent time, where I grew up, lived, or returned to. They are also places connected to the artists I collaborate with on this project—whether they return to them, dream of them, or imagine them. These locations deeply imprint their artistic practices.

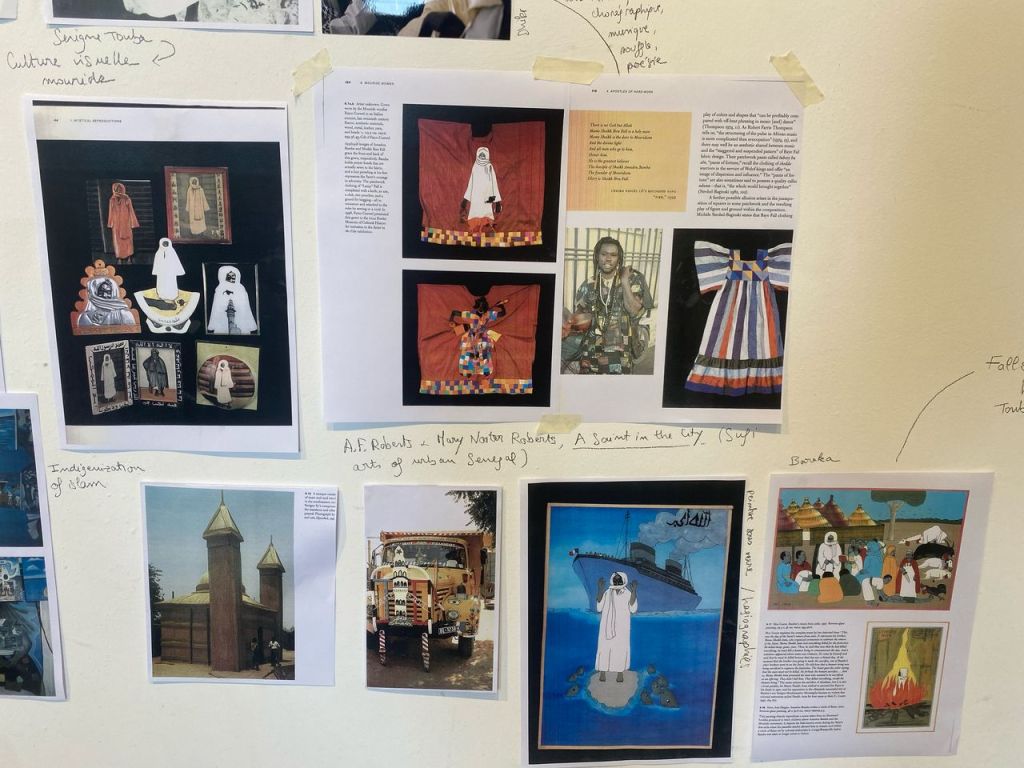

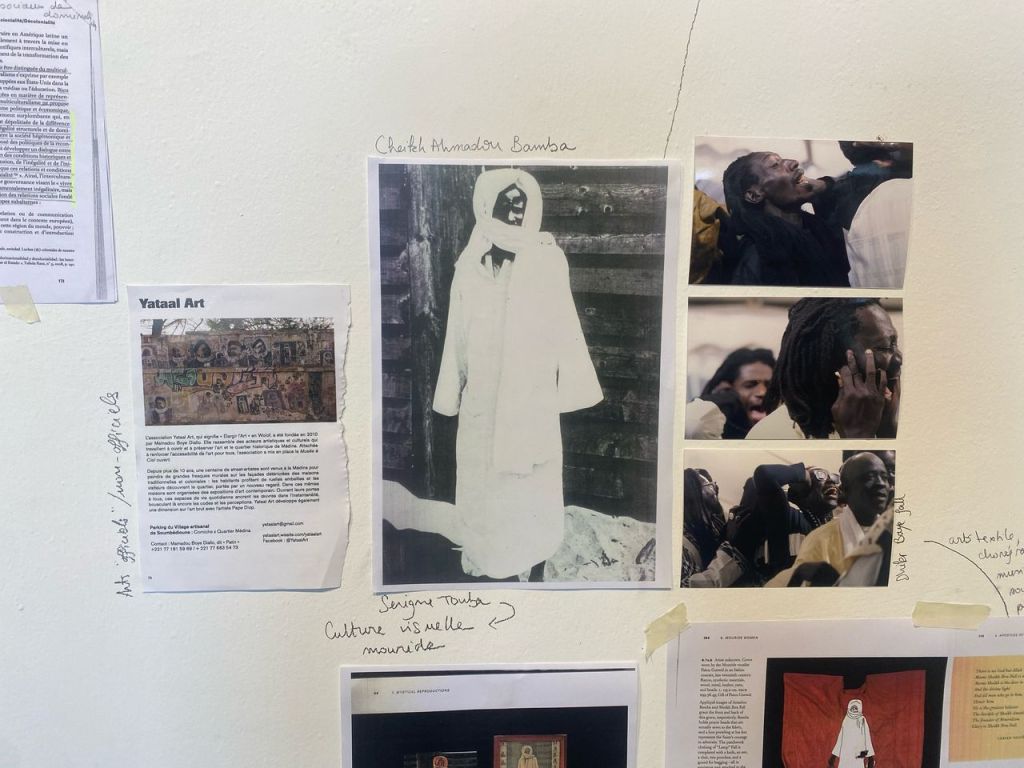

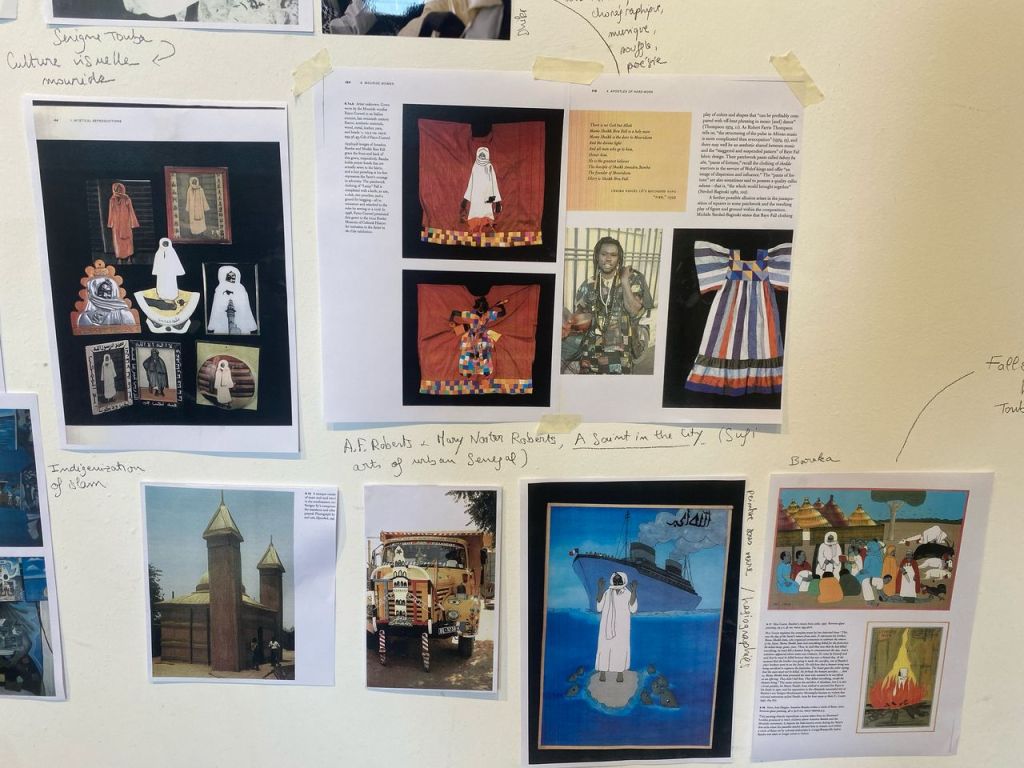

What struck me the most in Senegal is the way creation is embedded in every moment of life. Unlike in other contexts, there is no separation between artistic creation and daily life. Ritual practices and the sacred are intrinsically linked to artistic creation, whether in dance, cinema, textiles, music, poetry, or literature. What is fascinating is that these creations do not need institutionalized art spaces to exist. They take shape outside official artistic frameworks.

Could you give some examples of this phenomenon in Senegal?

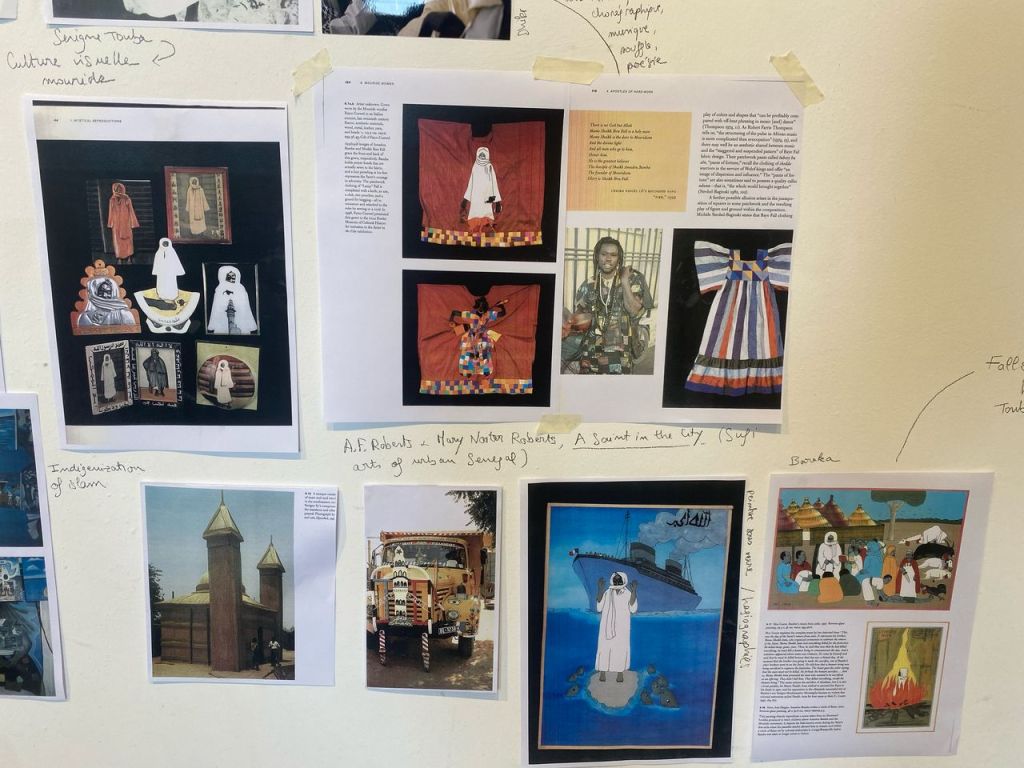

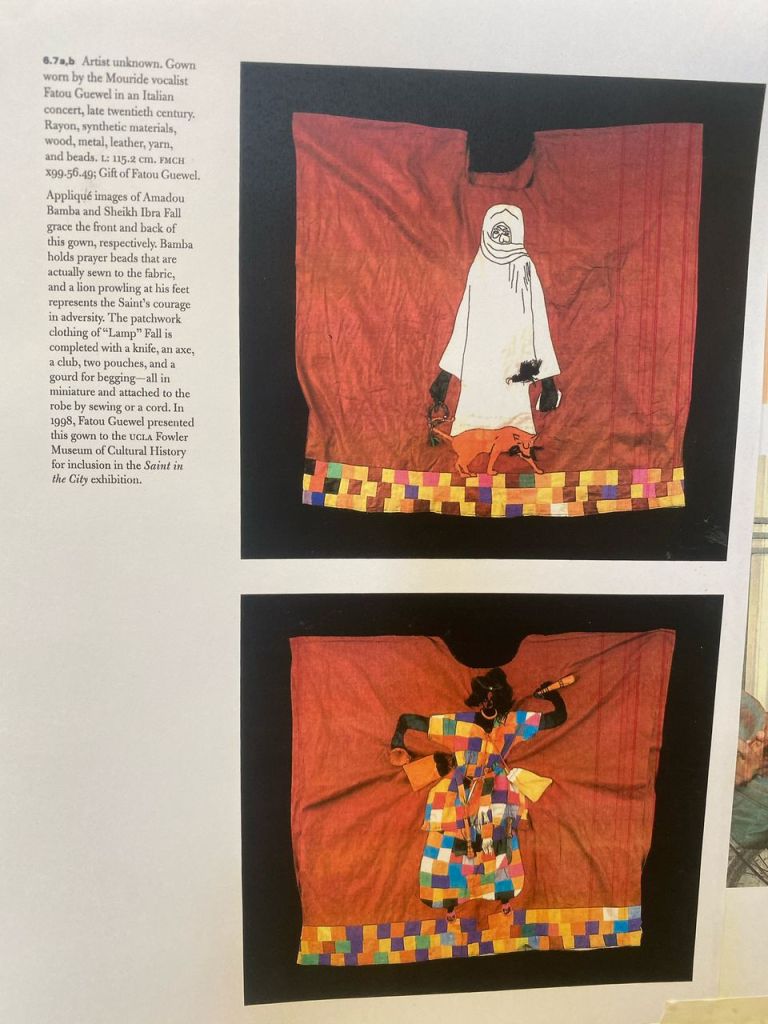

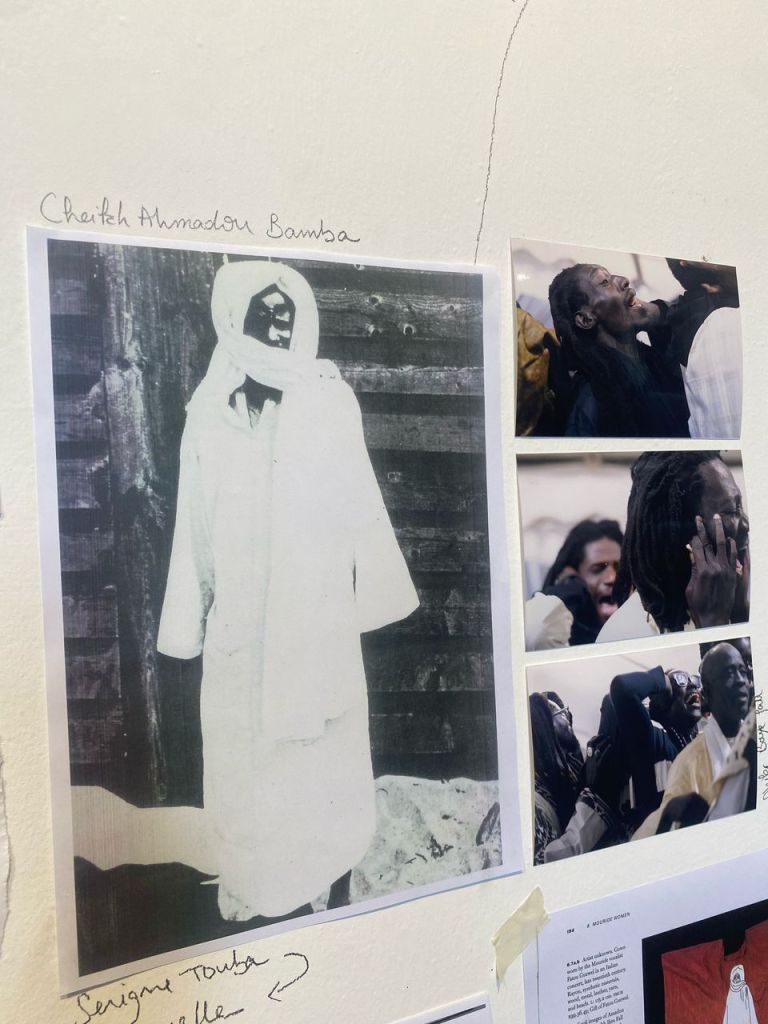

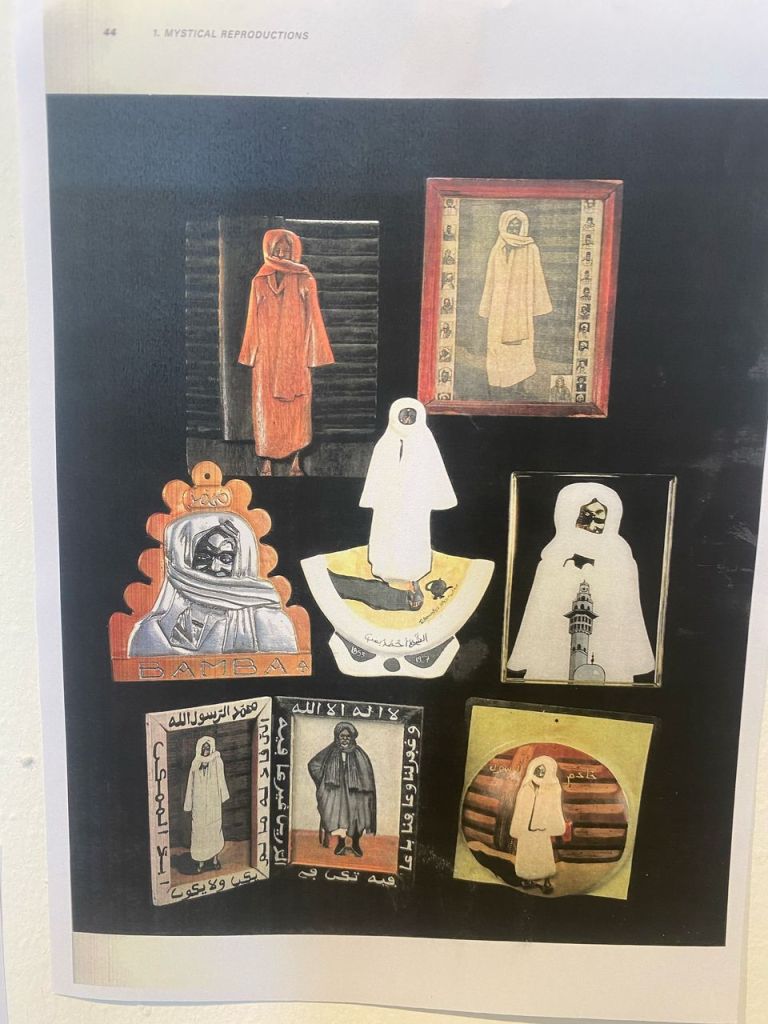

One clear example is the rich visual culture associated with Mouridism—expressed through murals, bus and car paintings, and sous-verre (reverse glass painting). It is also present in movement, breath, and choreographies inspired by prayer and rhythmic breathing. There is a musical choreography, but also in the garments crafted by those who practice these rituals. All of this represents a powerful and unique artistic creation.

What were the main challenges you faced during your research?

One of my key concerns, when working outside my own geography and community rituals, is avoiding an ethnographic gaze. I am not here as an analyst or anthropologist of rituals—that is not my interest. Instead, I focus on what artists create from these rituals. The main challenge of this curatorial research is setting boundaries to avoid falling into the traps of ethnographic analysis, which has well-known limitations.

Your research merges philosophy and spirituality, as reflected in the titles of the books displayed on the walls.

I draw a lot from political science, philosophy, and theology. The books displayed on the walls are the ones I brought with me from Tunis. I hadn’t planned on creating this wall initially, but these books have accompanied me throughout my research. The idea was to place them on the walls so that visitors feel free to take them, read them, and share this knowledge.

How do you understand the notion of resistance? Would you say it is the central theme for the artists you work with?

It is a recurring theme in the work of the artists I collaborate with, regardless of their geography—whether in Palestine, Zimbabwe, Lebanon, South Africa, Tunisia, or now Senegal. They engage in resistance against various forms of domination, erasure, occupation, apartheid, or even genocide. That is the common thread uniting all these artists—the will to resist obliteration and forgetting.

For the audience visiting this installation, what are the key messages you hope they take away?

Each visitor is free to interpret the installation in their own way. I have noticed that people with very different family or community backgrounds often identify with a particular element—perhaps a note, a bibliographic reference, or an artist. Ideally, I would love for visitors to take a pencil and add their own arrows, regions, countries, or concepts—making it a truly evolving and participatory map.

Leave a comment