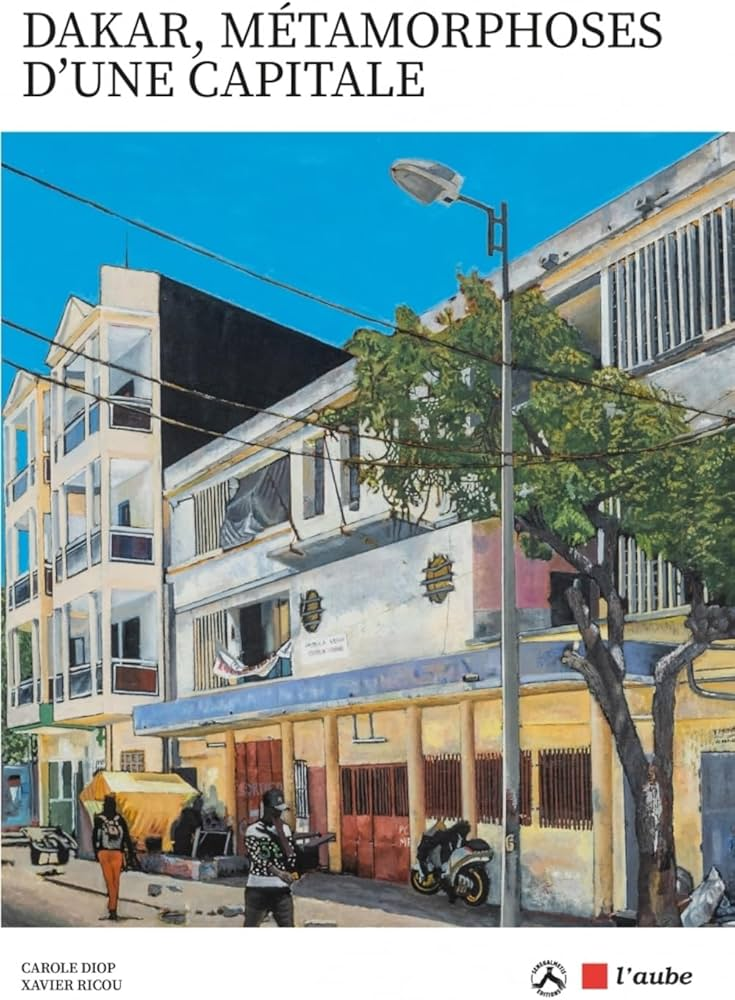

Carole Diop, an architect and cultural advocate, sat down with Dakartnews to discuss “Dakar, Metamorphosis of a Capital”, a book published in late 2024 and co-authored with Xavier Ricou. This work explores how Dakar, Senegal’s capital and once a key center of French West Africa, has grown and changed through its urban and architectural shifts, linking its storied past to its lively present. Known historically as a vibrant hub for art and culture in Africa, Dakar’s creative energy flows through these pages, a theme close to Diop’s heart as a member of Partcours, a network showcasing the city’s contemporary art scene. In this interview, she reveals the inspiration behind the project, her take on what makes Dakar special, and her views on why preserving its living heritage matters as the city faces rapid modern growth.

What motivated you to co-write this book on the metamorphosis of Dakar?

The idea sprang from complementary paths. Xavier Ricou, for the past twenty years, has been collecting archives on Dakar, driven by a passion for its history. He ran a Facebook page and blog called Sénégal Métis, where he shared old photos, postcards, and narrated the city’s evolution through these images. As for me, since 2017, I’ve been working with architect Nzinga Mboup on a research project called Dakarmorphose. Our goal was to explore the city’s development through the lens of traditional socio-spatial cultures. In 2018, during the Biennale, we held our first exhibition on the penc, the traditional Lebou villages, and the project grew with several new dimensions over time. The idea for the book took shape later, sparked by a collaboration with the Urban Economy Chair at ESSEC. With ESSEC students, I led an architectural walk through the Plateau district, while Xavier took them to explore Gorée. These exchanges gave birth to this work. Until now, no book had comprehensively traced the city’s history from both a historical and architectural perspective. The last major references, like Assane Seck’s thesis or Abdou Sylla’s book, date back to 1970 and 2000. There was a clear need for an update.

You also founded the magazine Afrikadaa and regularly organize Architectural Walks to explore Dakar. How have your own initiatives shaped your perspective on art and culture?

My architectural studies first opened the door to art in a broad sense. But in my classes on visual arts or art history, there was no mention of artists from the diaspora or the continent, nor their contributions to contemporary art. That struck me. So, I started a blog called Afrikadaa. Over time, it evolved into a magazine, and we published ten issues. When I returned to Dakar in 2013, Afrikaada became a platform to develop my artistic and cultural activities in the city. These experiences sharpened my appreciation for art and pushed me to actively engage in Dakar’s cultural scene. Teaching architectural history and being passionate about art also fueled my desire to dig deeper into the city where I grew up. I found inspiration in things like Xavier Ricou’s page, which influenced and enriched me. All of this came together in this book.

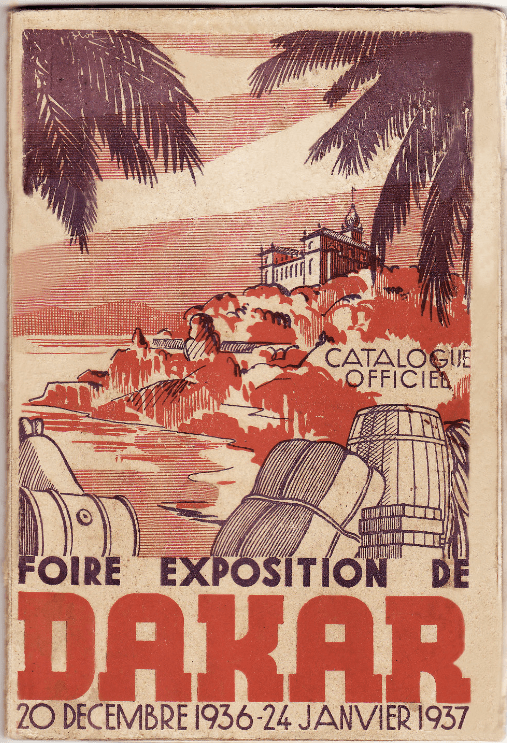

In the “Cultural Hotspot” section of your book, we learn that the first exhibition in Dakar took place in the 1920s. You describe the arrival of “Africanist” painters during this period as an early artistic milestone for the city. How do you assess their influence on the local art scene?

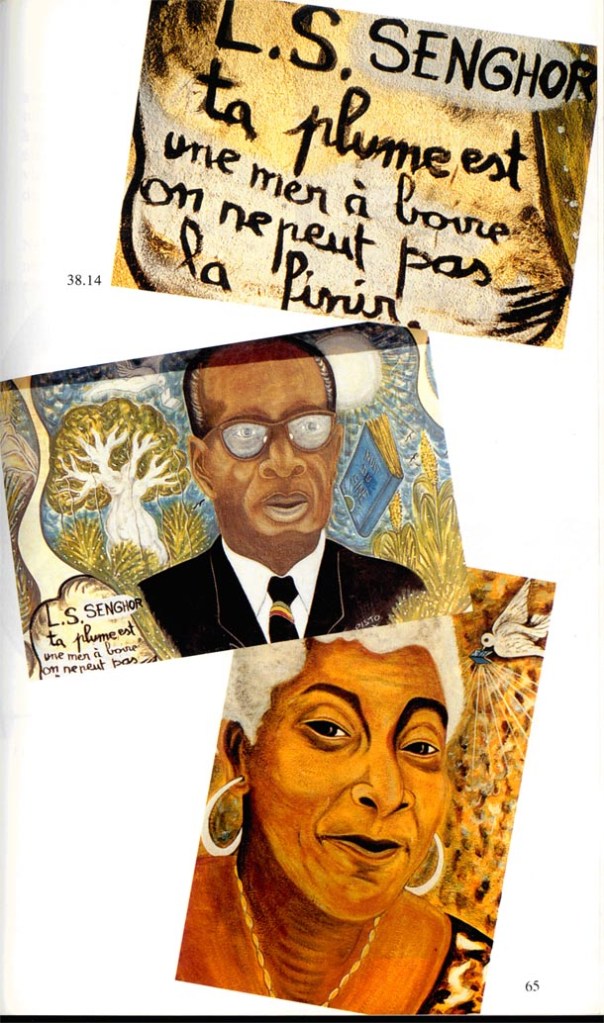

Several artists, inspired by Dakar, showcased their work here. Among them were Africanists, but also Europeans who honed their artistic practice locally. Events were held at the City Hall or the Chamber of Commerce, with regular exhibitions. As the capital of French West Africa (AOF), Dakar was a crossroads, giving it artistic significance. For instance, an artist like Anna Quinquaud created the sculptures for Dakar’s cathedral, drawing inspiration from young Fulani women—you can see their hairstyles and features in the angels she sculpted. These artists had a tangible impact on the city. The Africanists, in particular, shaped Senghor’s vision. German ethnologist Leo Frobenius, for example, documented African culture, inspiring Senghor, who said figures like Frobenius helped him rediscover the continent’s richness.

Senegal first welcomed European painters before its own talents emerged. How did this transition give Dakar a unique artistic scene?

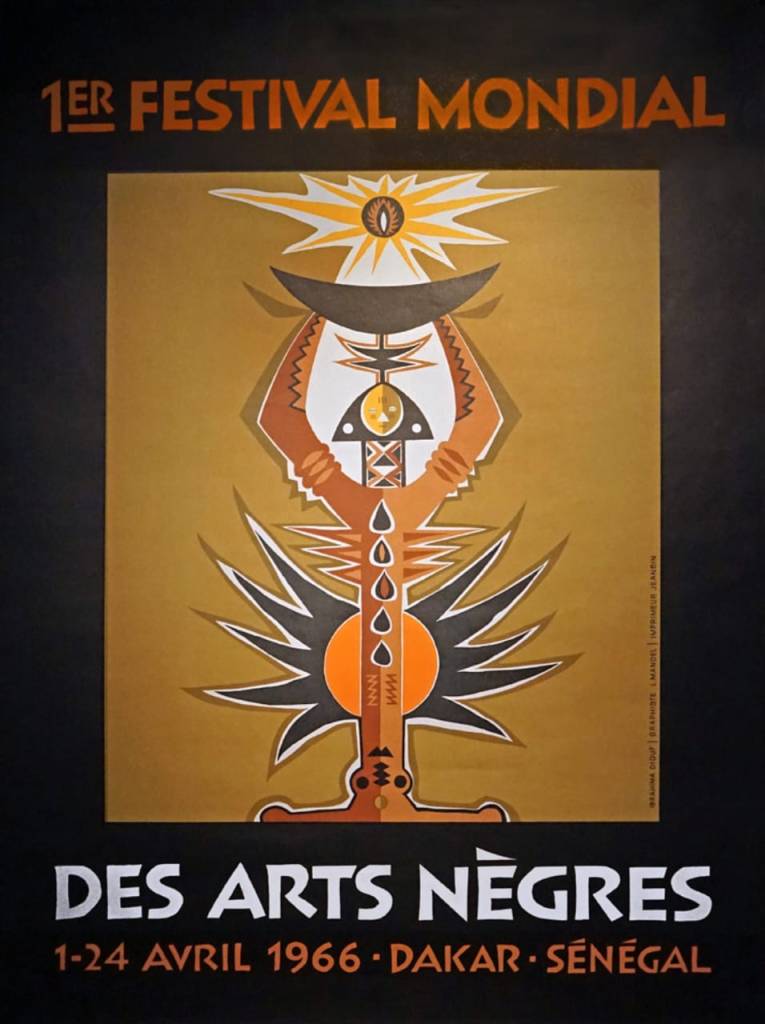

Senghor had a clear vision: he wanted a distinctly Senegalese architecture. That’s why he founded the Dakar School of Architecture in 1972, to train a generation of architects capable of creating modern designs rooted in local identity. Before that, in 1966, he established the National School of Arts and built the Dynamic Museum for the first World Festival of Negro Arts (Fesman). For him, arts and architecture went hand in hand. Until 2021, the law even required public buildings to draw from Sudano-Sahelian architecture or incorporate his theorized “asymmetrical parallelism”—though that concept remains vague today. Buildings like the CICES, Senghor’s house, or the façade of the Kébé building in Dakar bear this mark.

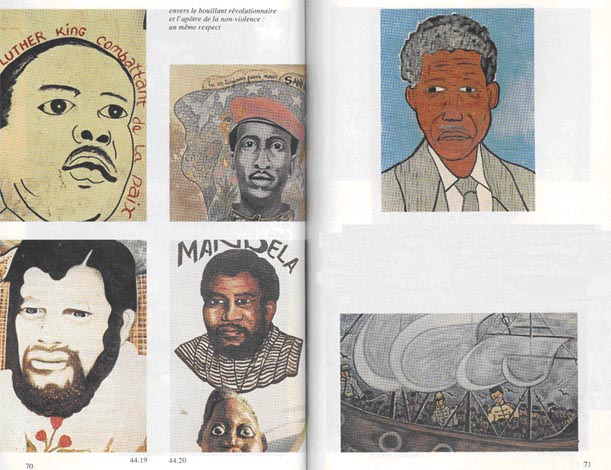

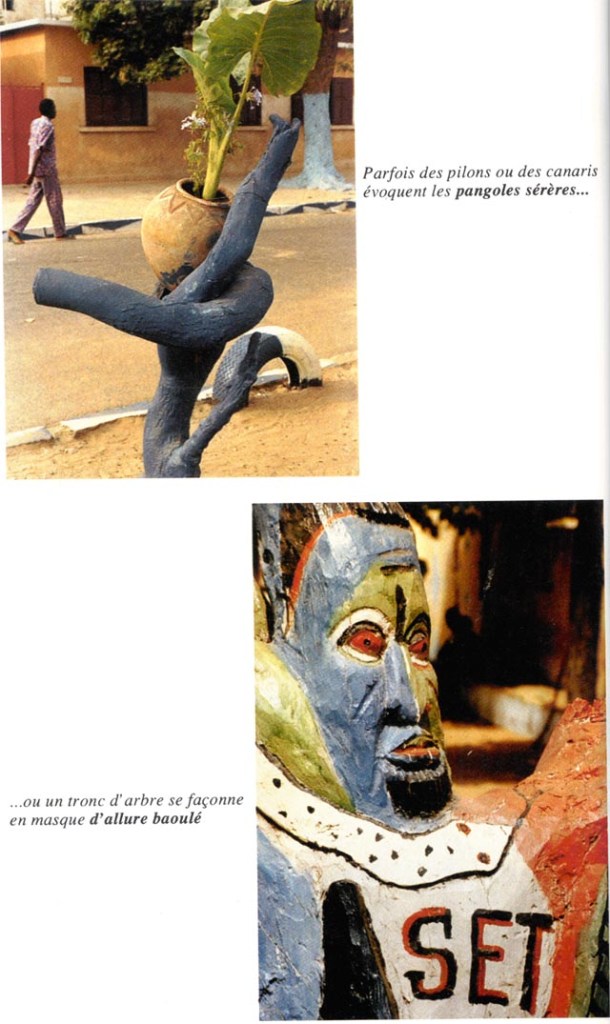

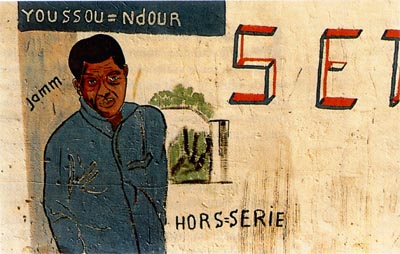

Later, in the 1990s, you mention the socio-political movement Set Setal, where young people covered Dakar’s walls with murals to revitalize their neighborhoods. How did this spontaneous surge redefine artistic expression in the city?

Urban cultures emerged in the 1980s and ’90s, especially in working-class areas like the Médina. These young artists had demands, and this spontaneous art gave them a voice. To me, they were engaged artists. But the movement faded over time, partly because some were co-opted by politicians, which dampened Set Setal’s initial momentum.

Do you see these murals and initiatives as a form of informal architecture that complements your vision of Dakar?

I wouldn’t call it informal architecture, but these murals and street art undeniably contribute to the city’s image. Walking through the Médina, you uncover pieces of the neighborhood’s history through these works—the names of collectives, past demands. You can also see how artists have evolved: a mural from the 2000s sits next to a recent one, showing shifts in their practices. These walls are living testimonies. Documenting these expressions is vital because a wall can vanish overnight. Wagane Gueye’s film The Walls of Dakar, for instance, beautifully captures what the city was like in the 2000s.

Which Dakar neighborhoods do you think fully embody this urban artistic creation?

It’s the Médina. Along with Niayes Thiokhers, these are areas where many artists emerge—Ousmane Mbaye, the designer, or Youssou Ndour, for example, hail from the Médina. I call it a “muse area” for its artistic vibrancy. Perhaps because it’s the historic extension of the Plateau. Established in 1914 to relocate indigenous populations away from the colonial city center, separated by Avenue Malick Sy, it became the first popular district. In that context, shaped by segregation, the Lebou villages regrouped, and art naturally flourished. The city then expanded, with significant growth in the 1950s.

What echoes of this urban art movement do you see in Dakar’s contemporary artistic practices?

Figures like Docta keep this legacy alive with Festigraff. We’re also seeing more women in graffiti, and young collectives are picking up the torch. Generations shift, but the momentum endures. It’d be fascinating to track these same artists in 2025 to see how their practices evolve.

In the book, you mention artists like Ndoye Douts, Fally Sene Sow, or Saadio, who draw from Dakar’s energy—its streets, its chaos, its life. How has the city itself become a muse for today’s creators?

Dakar offers a wealth of inspiration: everyday scenes, the immediate environment, and the interplay between artists. Collective dynamics play a big role. Take spaces like the Médina or the Agi’Art lab—they’re places where this creativity thrives, fed by the city itself.

The 1966 Fesman left a lasting mark. What events carry on that legacy in Dakar today?

The Dakar Biennale of Contemporary African Art carries that torch. The latest edition was in 2024, and it remains a key event. There’s also Partcours, held annually, bridging the gap between biennales. Dakar’s art scene is still vibrant and dynamic. I’m convinced there’s a bright future for creative industries here. Partcours, as a private initiative, enjoys autonomy that lends it freedom. The Biennale, tied to the state, can face limits on its independence. For example, one edition saw works censored—a challenge to handle.

What are other challenges do you see for the art scene?

First, strengthening artists’ rights and protecting their intellectual property. Another is getting African artists fully into the global market. In Dakar, for instance, there aren’t many truly commercial galleries able to showcase artists at international fairs. Beyond a few exceptions, I feel artists don’t yet have the recognition they deserve.

Chanel’s 2022 fashion show highlights Dakar’s international spotlight, followed by two consecutive exhibitions in recent years. Do you think such events bolster the city’s cultural identity or risk overshadowing it with a globalized image?

Chanel choosing Dakar wasn’t random—the city didn’t just fall into their lap. That said, how it was handled is up for debate. I’d have liked more involvement from local art scene players. Chanel brought its own vision of Dakar, which is open to question. The event boosted the city’s visibility, but does it strengthen or dilute its cultural identity? I’d say both.

Yes, because big brands often arrive with their own, sometimes fantasized, idea of Dakar. No, if local actors can assert themselves and infuse their touch, keeping the city’s identity intact. At the 19M Chanel exhibition, some Dakar artists were featured, and the latest edition included cinema and crafts, hinting at local identity. Yet there’s still a tendency to pick works or artists that appeal to the West. I’d love to see events of this scale driven solely by local talent, carrying their vision worldwide.

What trends do you notice in contemporary artistic creation among Senegalese artists?

We’re seeing more installations and videos. Painting still holds a strong place, but digital tools are gaining ground. Sculpture persists, though few young artists focus on it alone. Instead, there’s a rise in versatile artists exploring multiple mediums.

What Dakar’s art scene might look like in 20 years?

I think we’ll see more private initiatives like Partcours and a boom in commercial galleries. Over the past decade, new spaces have popped up where there were none—it’s remarkable. I hope this trend continues, backed by patrons and bold private projects.

Your book includes a manifesto to “save Dakar’s soul.” What message do you have for artists, policymakers, or residents to preserve the city’s cultural dimension?

We must preserve Dakar’s identity—its historically and architecturally significant buildings, and even some of its wall art. Though these murals are ephemeral, keeping traces of them matters. It’s not about freezing the city or turning every wall into a heritage site—it needs to keep evolving—but about documenting, celebrating artists, and safeguarding their work. That’s how we protect Dakar’s cultural soul amid change.

Read also

The World of Senegalese Contemporary Art Through Sylvain Sankalé’s Eyes

Why Dakar Stands Out in the World of Art! A Conversation with Wagane Gueye

Leave a comment