From March 19 to June 30, 2025, Paris pulses with a celebration of African and diasporic artistry, and nowhere is this more evident than at the Centre Pompidou. On its futuristic facade, Gérard Sokoto’s piercing self-portrait announces Paris Noir, a groundbreaking exhibition on the 6th floor that marks the Centre’s final showcase before a five-year closure for renovations. This is no ordinary display: Paris Noir brings to light 150 Black artists whose time in Paris shaped their work, yet whose names have long been overlooked. From the struggles of anticolonialism to the rhythms of négritude, their art tells a story of resilience and beauty. For Afrodescendants visiting the exhibition, it’s a moment of profound pride—a chance to see their history celebrated, their voices amplified, and their legacy reclaimed.

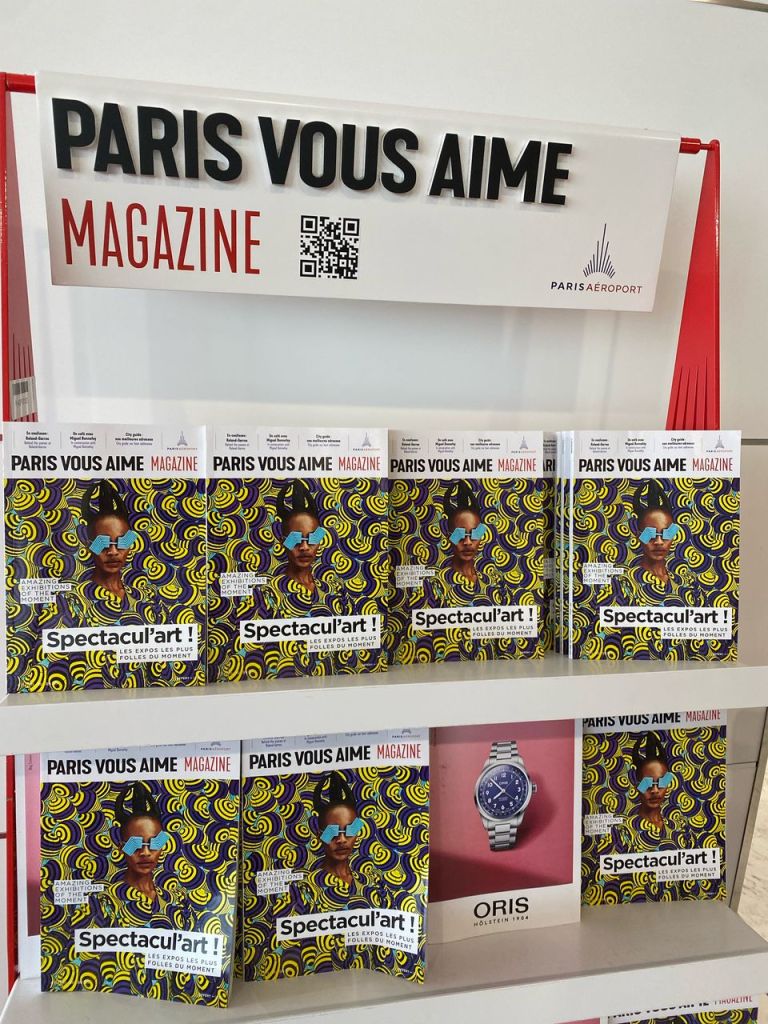

A springtime sun bathes Paris in light, and from Roissy-Charles-de-Gaulle Airport, Africa sets the stage. The cover of the free magazine Paris vous aime showcases a vibrant work by Kenyan photographer Thandiwe Muriu, drawn from the Wax exhibition at the Musée de l’Homme, celebrating African artists’ reappropriation of wax textiles.

But the heart of this season beats in Beaubourg, in the lively neighborhood near the Marais, where the Centre Pompidou hosts Paris Noir, an exhibition that resonates deeply with Afrodescendants by giving voice to overlooked Black artists.

On the futuristic facade of the venue, a piercing gaze captures attention: the oil-on-cardboard self-portrait by Gérard Sokoto, the exhibition’s poster image. This pioneer of South African urban art, a jazz pianist who settled in Paris in 1947 and died in 1993, is unknown to the crowd rushing to the entrance.

Like him, the 149 artists featured share a common thread: their Black identity, their time in Paris, and a recognition long denied. “While Paris was a unique space of solidarity between Africa and the Americas, France has never highlighted its role in the emergence of Black cultural practices,” explains Alicia Knock, the exhibition’s curator. Paris Noir seeks to right this wrong, unveiling vibrant works and anticolonial struggles from 1950 to 2000.

On the 6th floor of the Centre Pompidou, where the exhibition unfolds, the emotion is palpable. “At last, an exhibition about Black people in Paris!”. Élise, from the French Caribbean, stops, struck by The Concern (Le Souci) by Joseph Réné-Corail, a painting that evokes the artist’s imprisonment in Paris in 1963 for his activism for Martinique’s autonomy.

“I see sadness, melancholy. The character seems trapped in a cage, behind bars, like the artist himself was. We can’t break free. But here, we’re finally seen,” she shares, her eyes shining. For Élise, this exhibition is a breath of fresh air, a moment where Afrodescendants can recognize themselves and feel valued, honoring struggles like Corail’s fight for freedom.

The exhibition explores multiple themes, combining formal aesthetics (Afro-Atlantic Modernisms, A Leap into Abstraction) with political and spiritual dimensions (Revolutionary Solidarities, Memory Reappropriations, Self-Affirmation).

“What really moves me here is the richness of expression. There’s a soul to it, a kind of Negritude, a Black sensibility,” says Martin from Guadeloupe, smile lighting up his face. “They make me proud of who we are, of what we’ve created“, he adds.

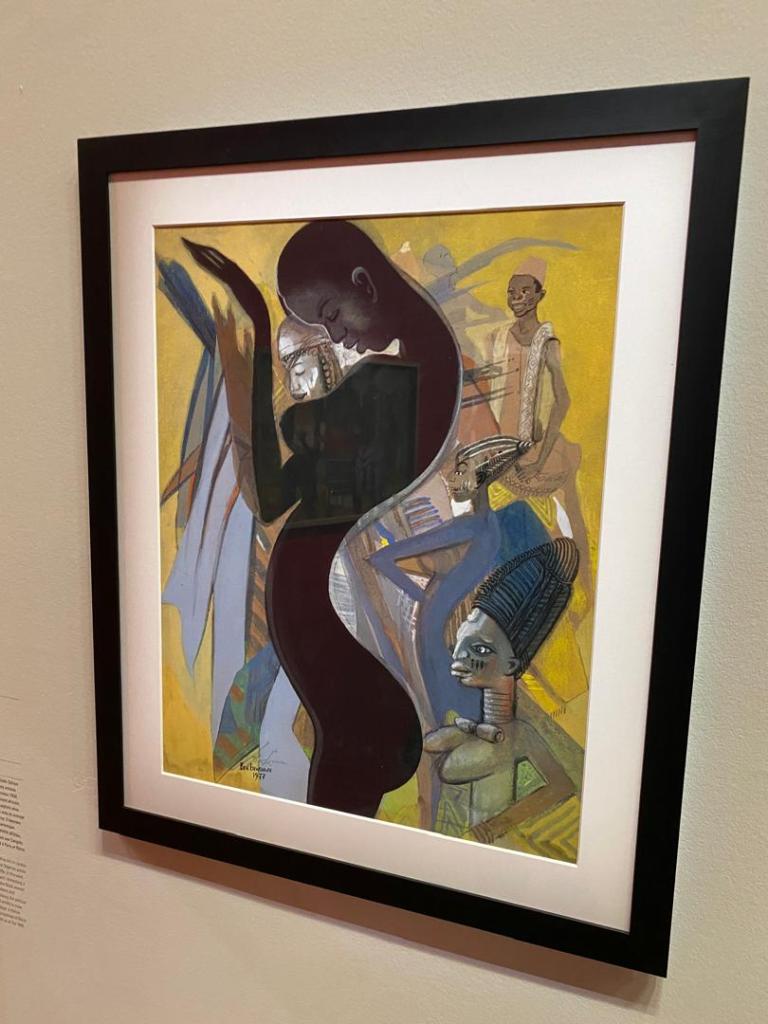

Negritude itself — the literary movement born in Paris between the World Wars around Senghor, Césaire, and Damas — finds a visual echo here. The watercolor Negritude by Ben Enwonwu (1977) converses with a tapestry by Papa Ibra Tall, a pioneer of the Dakar School. With its vivid colors and rhythmic composition, the piece embodies Senghor’s ideal of African art: rooted in movement, emotion, and spirituality.

The exhibition also pays tribute to the legendary journal Présence Africaine, founded by Alioune Diop, and to that postwar Paris of the 1950s and ’60s, where African students, Caribbean writers, and African American militants crossed paths.

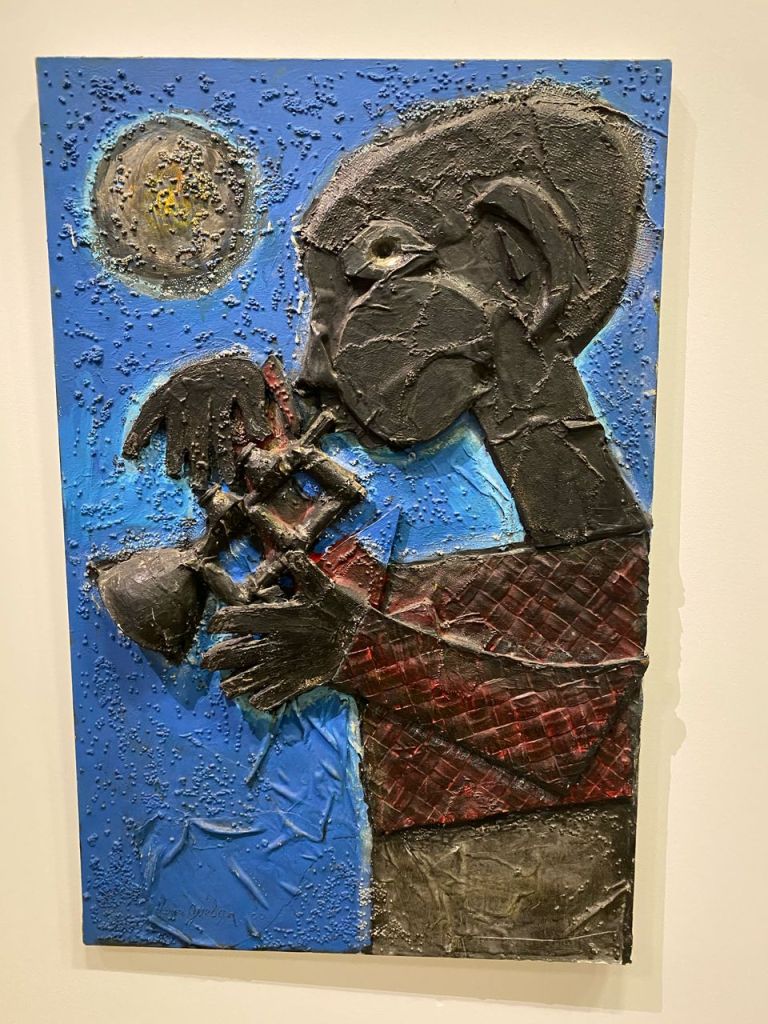

The scenography of Paris Noir follows a circular path, inspired by Édouard Glissant’s philosophy of Tout-Monde — the interconnectedness of all cultures. Visitors move from the explosive abstraction of African American artist Ed Clark to the visual poetry of Wifredo Lam. Iba Ndiaye’s The Blues Singer is a vibrant tribute to the American blues and jazz singer, Bessie Smith. Henri Guédon, using mixed media, makes Miles Davis dance across the canvas. Nearby, Robert Radford depicts the island of Gorée, while Fodé Camara paints a haunting memory of slavery, showing a body breaking free from its chains.

These pieces, blending jazz, memory, and affirmation, strike at the heart. Like Sokoto’s self-portrait, they question, unsettle, and above all, uplift.

Collection Gladys et Laeticia Guédon

“I feel incredibly proud”

Patrick Case, an Afro-Canadian and former human rights lawyer, seems to be moved before a sculpture by Christian Lattier, winner of the visual arts’ grand prize during 1966 World Festival of Negro Arts in Dakar.

Lattier’s Christ is represented through a structure made of iron, rope, and wood. However, the artist repurposes them here to create an expressive, almost tormented human figure with exaggerated proportions: the hands and feet seem oversized, almost disjointed, emphasizing suffering or perhaps the universality of this martyred figure. The body appears more suspended than nailed, caught in a tension between falling and ascending. The work can be read as a colonial reinterpretation of the Christian symbol. Christian Lattier, an Ivorian sculptor trained in France, often explored in his work the dialogue between African traditions and Western modernity. This Christ could embody the tension between cultures: the Christ of the missionaries revisited through the suffering of colonized peoples—or perhaps an African Christ, returned to his flesh, his pain, and his resilience. The sculpture could also evoke a universal spirituality, transcending dogma to speak to the fundamental human experience: suffering, sacrifice, and redemption.

“My older brother, who is now deceased, was a student at the Sorbonne and lived in Paris for a long time. At that time, I was living in England. He often told me about the experiences of Black communities in Paris, particularly in relation to the Présence Africaine magazine. During that period, the anti-colonial movement in French colonies was very active, and my brother shared a lot of that knowledge with me,” Case says.

“I feel incredibly proud. These artists are so accomplished, and the art is fantastic. I had no idea this art existed before now. It’s amazing to see the incredible work that comes from the African diaspora in France, and it fills me with pride. This exhibition can definitely contribute to a better understanding and respect for the history of African Americans, as well as those from African nations that were colonized. Art has such power to convey emotions, history, and experiences, and this exhibition brings all of that into focus in a new way,” he adds. For Patrick, Paris Noir is a bridge between past and present, a celebration of the African diaspora that inspires one to stand taller.

Khalifa Thiam, a Senegalese man who studied in Paris before teaching English in Scotland, shares this sentiment. “Back then, we were invisible, culturally absent. I stumbled upon this exhibition in the metro, and it’s given me strength. As a Black person, you feel reinvigorated, proud. We exist, and we’re showing it!” he says, his eyes sparkling. For him, as for many, Paris Noir is an affirmation: Afrodescendants have a history, an art, a voice.

Still, not everyone agrees on everything. Some visitors worry that the exhibition might flatten too many complex stories into a single narrative. The memory of slavery in the Americas, the independence movements in Africa, migration, and diaspora — each has its own specific history that deserves distinct treatment.

Nevertheless, Black Paris is a turning point. “I hope this isn’t just a passing moment, but a new beginning,” says Élise. “It was long overdue.”

Read more

In Dakar, Carole Diop Maps a City’s Art and Past

Why Dakar Stands Out in the World of Art! A Conversation with Wagane Gueye

Leave a comment