During his visit to Senegal in Winter 2025, DakArtNews met with Modou Dieng Yacine, a Chicago-based artist born in Saint-Louis, Senegal, in 1970. A graduate of Dakar’s École des Beaux-Arts and the San Francisco Art Institute, he blends painting, photography, and collage, using materials like denim and burlap. His art has been exhibited at numerous venues, including the Studio Museum in New York, Smithsonian National Museum of African Art, Museum of African Diaspora Arts, New York, and the Dakar Biennale of Contemporary African Art. His works are also held in the collections of the Studio Museum, the Smithsonian, and the Kranzberg Arts Foundation. Dieng’s practice explores, among others, identity, habitat, memory, and migration. A curator for Blackpuffin at the Seattle Museum of Art in 2023, he will exhibit during the Venice Biennale of Architecture from May 8, 2025. In this interview, Modou reflects on his inspirations, Senegal’s art scene, curation, and an African art economy, offering a perspective on art as beauty and connection.

You are visiting Senegal; what have you done so far?

I’ve been soaking up inspiration, observing what’s happening, and exploring the resources available to artists. It’s been great to see the shows, the fashion, and the people walking down the streets. I haven’t been here in two and a half years.

You grew up in Senegal before moving to the US. How has this shift in context affected your approach to making art?

I grew up here in the ‘90s and was already an artist before I left. Back then, culture was being explored, but it wasn’t as vibrant, business-oriented, or colorful as it is now. My goal was to discover the country of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Andy Warhol, James Brown, and others, and to engage in a larger market and conversation, which I did. Since then, I’ve been trying to combine what is here in Senegal and what was going on in the US, bridging the gap.

Have the topics you explore changed?

They’ve never changed because they’ve always been my focus: architecture, habitat, the spaces where we build our identities, and finding ways to express beauty. It’s just been amplified. I don’t think the Atlantic divide is as wide as we imagine. The same conversations about identity, ancestry, being Black, and being African are happening on both sides.

You were born in Saint-Louis, a city with a rich colonial history. How does this historical dimension resonate in your work?

I recently spoke with my friend, artist Oscar Murillo, about habitat and space. He said Saint-Louis was my trauma, and that’s why I’m an artist. He’s right. I was born there, and life was beautiful—everything seemed perfect. But growing up, I realized it wasn’t built for me; it was made for someone else. Saint-Louis was designed for the French to run Africa.

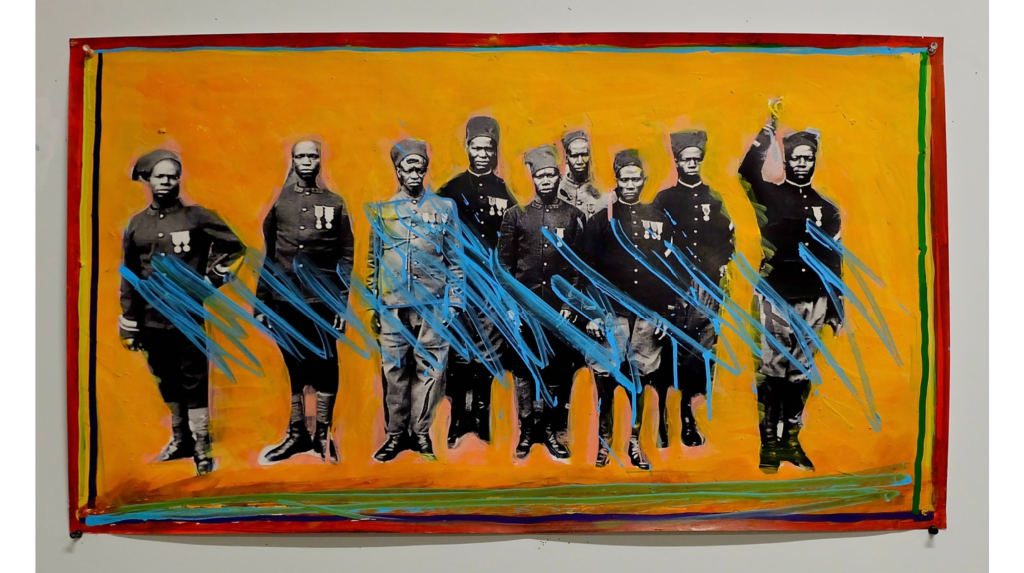

When I visited France’s Mediterranean coast, it looked just like Saint-Louis. I realized the city’s infrastructure was imported. That postcolonial trauma is part of me, and I claim it as my identity. I’m not trying to erase it. The question is, how do I digest it and make it beautiful, interesting, and rewarding? How do I move from trauma to therapy? That’s why most of my colors are colonial colors that I appropriate, infusing them with more energy and my Africanness—essentially recolonizing a colonial city. By doing so, I position myself as an experiment, so others in similar situations can process their own trauma.

Is that what drives you to explore topics like habitat and space?

Absolutely. For example, one of my recent series is called Venice, because Venice was a crossroads of civilizations, a colonial city with a Black population that later disappeared. You notice Black figures in doorknockers and frescoes there. It’s about space and habitat. The question is, how do we reconfigure and reconstruct the hierarchical spaces we live in? A mixed-race friend once told me that on a flight from Paris to Dakar, he’s considered white, but from Dakar to Paris, he becomes Black. This shift happens within the confined space of a plane, shaped by hierarchies based on skin color, hair, or language. We all experience this, so the challenge is to represent it in visual arts without falling into division, instead fostering unity, convergence, and cohabitation.

How do you achieve that?

Look at my paintings. I did a series on Lumumba, the greatest African trauma, as he was the first hopeful leader brutally assassinated. Back then, leaders kept their minds in their pockets, and our generation wasn’t told about Lumumba. So, I went to Brussels, to the African neighborhood of Matonge, and created portraits of Lumumba based on photographs. These Lumumbas resemble soccer players, musicians like Papa Wemba, or street vendors. The idea was to diversify the vision of Lumumba.

What do you aim to achieve with your art through these themes?

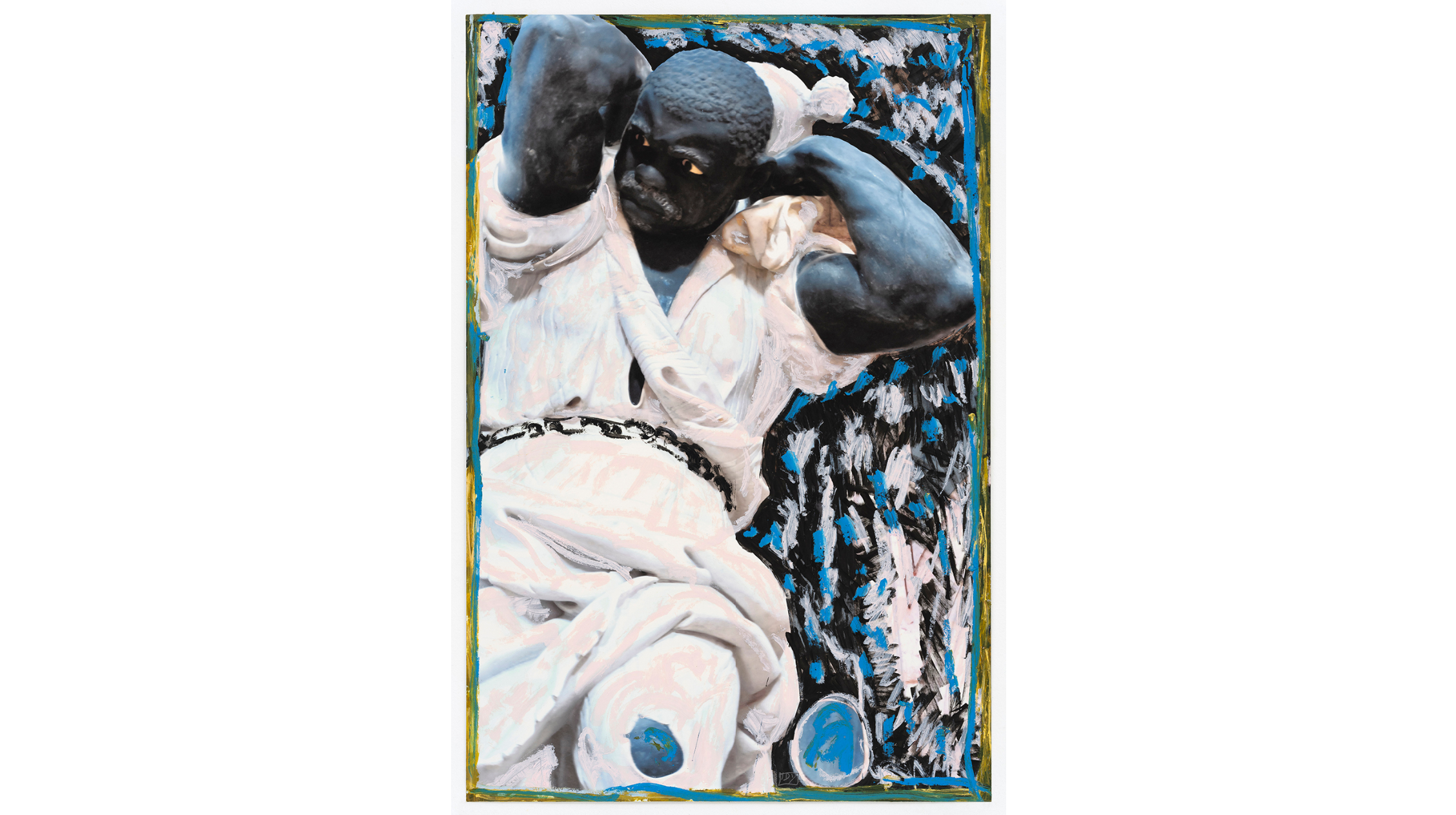

For me, art is about the physical—someone has to create it; the spiritual—we’re searching for answers beyond ourselves and our space; and the material—the objects we produce. How do we combine these three aspects? It’s not just about the objects; it’s about performative art because you have to capture the time, the moment, the energy, and the conversation around you. That’s the bigger picture for me. Then, you need to know who you are, have a voice, and share it with your people while creating an umbrella called beauty. How do you capture that energy, that silence, in an object? My studio practice now focuses on combining American abstraction and French figuration. The body is present, especially the Black body, but it’s not just about that—it’s about the body in general, the space, and how we navigate the parameters of identity, culture, and postcolonial spaces. There’s an African renaissance happening, not only in art but also in literature, filmmaking, music—especially Afropop. Africa has given birth to cosmopolitan megacities that are vibrant, smart, and influential in technology and fashion. That’s what I’m trying to capture and translate into my paintings and practice. Everyone has their own mark. I’ve found mine in combining abstraction and figuration, like Basquiat, who pioneered this for Black artists, or Aboudia, who’s taking it to new spaces. We see Black figuration emerging through the Ghanaian school. We’re pushing this conversation forward.

In one of your interviews, you described Chicago, where you’re based, as a center of Black Renaissance. What does that mean in the context of your work?

It means I’ve always wanted to interact and work with artists of different identities within the Black diaspora. Chicago is the city of Obama, Oprah, Michael Jordan, Kanye West, Kerry James Marshall, and more. All those energies, practices, and ideas are there, and I’m grateful to have access to them anytime. Chicago was a magnet for the Great Black Migration, and today, it has a large East African and African community. That’s what I call a Renaissance—the best of what Black people have to offer the world. There are also galleries sensitive to Black arts, which enrich my practice.

You speak of identity and the Black/African condition. Do you see yourself as a mediator between Africa and the West?

No, I’m not. I’m a mediator between my personal culture and my audience—people interested in understanding what it means to be a Black man born in Africa, traveling the world, living in the West, and making paintings. My job isn’t to explain to the West what it means to be African. I’m an African, and I speak to those who get it.

You’re an artist and also curator. How do you combine both?

I had the privilege of meeting the late Nigerian curator Okwui Enwezor, my mentor at the San Francisco Art Institute, where he was dean. He told me, “Modou, if you feel lonely, curate,” because it gives you a reason to call your friends and talk about art. That’s how I started curating. After my master’s, I taught for years to pay the bills but needed to keep the conversation alive. I opened a small space, inviting artists to exhibit and discuss their work with me. I was an artist curating, not a professional curator, which is different—it’s a passion, not a job. Now, you see artists like Jeff Koons, Kehinde Wiley, or even Pharrell Williams curating. The goal is to create an art economy for Africans and the African diaspora, something we didn’t have before. When I started in Senegal, buyers were mostly European tourists. Now, most buyers in Africa are Africans. So, how do we build a production and economy for our own community and culture—an art-based economy? That’s what we’re doing, and that’s our contemporary art. Everyone has their own contemporary art; this is ours.

Do you think there is such a thing as contemporary African art?

I think there’s contemporary art made by Africans, just as there’s contemporary art made by the French, Koreans, or Japanese. The world needs this more than ever because African contemporary art has been overlooked, yet we’ve long contributed to shaping how this universe functions. The world is a global village now, so the conversation isn’t siloed—it’s open to everyone.

You’ve spoken about forging your own artistic voice across African and Western contexts. How do you define authenticity in your work?

Authenticity is personal, defined by the self, not others. How can we call someone inauthentic if their expression is true to them? As long as your voice is genuine, you’re authentic. Previous generations, trained in Europe or Russia, returned to Africa seeking authenticity through materials or processes, contrasting their “European” education. But I don’t see education as European or African—it’s just education, a tool for practice. Discovering Basquiat saved me from this debate. He was authentically American, living on New York’s streets, creating art inspired by Picasso and primitivism, yet he claimed his identity as SAMO. His work had an African authenticity, but not in Africa. Authenticity is personal—be true to your voice.

Who has influenced you the most?

There are too many to name, but I love Stanley Whitney for his abstraction and Picasso for how he deconstructed space to make it flat while retaining the three-dimensionality of the body. Every artist inspires me. My job is to look at their work and take something from it. As Picasso said, “Good artists borrow; great artists steal.”

Your work dwells on the notion of asymmetrical parallelism. Can you tell us more about that?

This concept comes from Léopold Sédar Senghor, who faced a challenge: he inherited a country built to mimic European cities and wanted to reinvent spaces that resonated with our way of life. He believed our architecture shouldn’t just be geometry and space—it should have rhythm, like jazz, which Black people infused with rhythm from classical music. His house reflects this: even with parallel lines, there’s an asymmetry that creates rhythm. I approach my canvas the same way. Though it has four walls and dimensions, I flatten it to three dimensions, removing one to create rhythm. That’s where asymmetrical parallelism comes into play in my art.

How do you think your art is received here in Senegal?

I hope my work is well-received. My last show was during the Dakar Biennale in 2022. The art scene here needs to open up and grow in scale. I’m more curious about what ordinary people think of the art happening here than the opinions of the local art scene. That’s a broader conversation we need in Dakar. Perhaps if the president bought art or visited galleries on TV, it could spark public curiosity and draw people to exhibitions. Art hasn’t yet reached the level of music or cinema here.

What is your current exhibition project?

I’m working on a show called Dakar, which will take place in Copenhagen.

*Photo credit of the first image: Lawrence Agyei

Read also

In Dakar, Carole Diop Maps a City’s Art and Past

The State of Contemporary African Art Today: Dr. Ibou Diop’s Critical Perspective

——————————————————————————–

To support Dakartnews’ mission, your contributions are warmly welcomed on our Donate page.

Leave a comment