In the village of Touggana, a quiet settlement on the outskirts of Marrakech where the city’s frenetic energy gives way to open sky and sparse olive groves, Mohamed Baala — known as Mo Baala — welcomed DakArtNews into his studio, a space that feels worlds apart from the tourist circuits and gallery districts. Baala, 39, does not speak of art as vocation or intellectual exercise but as an urgent, lifelong necessity. Born in Casablanca in 1986 and raised in Taroudant, he is entirely self-taught, having developed a multidisciplinary practice — encompassing painting, collage, installation, performance, sculpture, poetry and music — through years of street survival, market labor as a vendor in the souks, and solitary, voracious reading.

What emerges most powerfully in conversation is the rare equilibrium he maintains between two forms of knowledge: a sophisticated engagement with philosophy and poetry — citing Rumi, Heidegger, Carl Jung, Mohammed Jammal… with natural ease — and a profound, hard-won understanding of life at the margins, shaped by childhood hardship, family rupture, decades as a vendor in the souks, and close observation of human behavior in its rawest forms. These strands do not compete; they intersect, producing a visual language that is poetic, unflinching and deliberately elusive.

His paintings and assemblages, crowded with hybrid figures, insect-derived colors and deliberate ambiguities, function as what he terms “confessions of the subconscious.” Beauty, in his view, often serves as a trap — a vibrant lure that softens tragedy and delays comprehension, mirroring the multiplicity of truths he encountered while trying, and failing, to distill a single narrative of his parents’ divorce.

In the extended interview that follows, conducted in his studio, Mo Baala reflects candidly on art as a space of radical freedom and ethical responsibility: a practice that processes personal and collective pain without perpetuating violence, that embraces fluidity over sharpness, and that insists on remaining human — even gentlemanly — amid experiences that could easily harden the heart.

What is Art for you?

Art is something we’re tired of even as a word. Anything you say can work—it can be banal, it can be noble. For me, I don’t want to call it autobiography because I don’t have just my own story. Whenever I talk about myself, I talk about my parents, my grandmother, my grandfather, my friends in the neighborhood—so many others. It’s a collective biography. I believe my work is a confession of the subconscious. Confessions of what is hidden. I’m always arguing with myself: how can I find perspective in flatness when all I have is a strong wall? How can I find a clear image in a silhouette, something clear in traces? Because I’m dealing with stories of other people—my mother, my father, my grandparents, my friends. I’m dealing with my parents’ divorce, which is linked to me. When they gave birth to me, they stayed together only a few years before separating. Growing up, I tried to understand why. It became a mythology—everyone tells different stories. I don’t have one specific truth; I have multiple stories. That taught me there is no single perspective on existence, no single point of view. That’s why I don’t have a clear message, a clear opinion, a clear art. Sharpness is not something I believe in. There is no sharpness in life. Even the artists I love the most—those I’m interested in aesthetically—are the people who have double meanings. That links me to poetry. For me, art is somehow poetry.

My work is not only about what I like.

How do you confront beauty in your work?

Beauty is a big philosophical conversation. The line separating ugliness and beauty is very fine—like the line between chaos and cosmos, right and wrong. I use colors not for beauty, but to banalize the tragedy of the subject matter. Most of the themes I deal with are dramatic, cloudy. If my work were also cloudy, it would be stressful. I want a complex conversation with the viewer’s eyes. When they come to my work, I would love them to feel: “That’s beautiful.” And then later they realize it’s a trap. A beautiful trap. And then I feel successful. But if they come and get the subject matter directly, I feel I didn’t create any distance between me and what I want to deliver—not just ideas, but emotions. In Arabic we say a phrase that means: what is a problem for some can be a positive thing for others. So ugliness or beauty depends where you stand—mentally, physically, historically. What is ugly for some people can be beautiful for others. What is beautiful for some people can be ugly for others.

Do you find your pieces beautiful?

They’re beautiful because they’re like my kids. You can’t say your child isn’t beautiful. Even if others see something far from a Roman sculpture, for me it’s my kid. I don’t believe in logic when it comes to my work. And my work is not only about what I like. I use colors I dislike. They don’t give me a good mental state. They don’t make me feel good. But my work is not me dressing and going to the street. In the street, I would wear what makes me feel good. But that’s not my work. My work is about political agitation. It’s about having a complex conversation with panic—being panicked in life. When you are a kid and you have no mama, no papa, and you’re thrown in the street, and you feel nobody is looking at you—not the state, not the people—and you’re treated like an insect. That’s why a lot of the colors I use come from insects. The palettes I’m inspired by come from insects. The idea of “you are an insect.” That state of being alone—not solitude, loneliness. Being trapped and having no solution. Jalal al-Din Rumi says something beautiful: the one who doesn’t want you will find a hole in the door to go out; the one who wants you will find a hole in the rock to come towards you. Even in complex situations, I believe in human beings finding a hole in the rock—some optimism—to be in a space where you can be a little comfortable with your existence instead of becoming a horrible person. Because pain and tragedy can make you a horrible person. And as a human being, I don’t accept that. I work so much on being a gentleman.

I lived so much in the street, so much life that is underground. And it’s very radical to be a gentleman. That radicality is the hardest work. I always look for kids who live in the street, or people who had the street in their life—then later became stable. I met people who lived six years in the street, and they speak politely, beautifully, serving you coffee. I think: they are a legend. Because usually they “should” be horrible persons after all that, but they are not. Not letting tough situations push you into revenge, into becoming horrible—this is an emotional material for me. Extremely important.

To exist is to appreciate whatever happens.

What is the reason of you making art?

I make art because it makes sense. I did so many jobs. But as I grew up, I found that all those jobs—it’s like I didn’t do them, because I didn’t go away for many years to become proficient in them. They have responsibility. And I think art doesn’t have responsibility. That shocks me and makes me interested: you are not responsible for anything. Your no is mixed with your yes. Your yes is mixed with your no. Your “I want” is mixed with “I don’t want.” That space that doesn’t belong anywhere has a poetical skepticism. A clear opinion for me is dangerous. I grew up with extremism. I grew up with different kinds of people. We say in Darija, “the head that doesn’t move is a mountain.” You have to learn to move. If you’re not flexible with existence, you become stubborn, you think you are right. One thing that interests me in art is that we have tough conversations with right and wrong, and with people who want to frame life. There are dictators, nationalists, fascists—people who want to say: my picture is better than yours.

Before aesthetics and art history, I was in philosophy. Hegel said “philosophy is like the owl of Minerva, which spreads its wings only with the falling of the dusk”. I love that. idea I love the bird because it never flies in a straight stable way. There is agitation in that movement. That’s what I loved in philosophy. Also, Gerhard Richter said something very simple and beautiful: “I am allowed.” I am allowed to do this. I am allowed to destroy my composition. I am allowed to be stupid. One of the most dangerous things we suffer from is not being allowed to be stupid. People always want to control: be this, be that. This is the only route.

But in art, I am allowed. And even an act like drawing a circle—it’s a circle, not a sharp circle. It’s cultural, universal, it means so many things. We could have a whole conversation about just that act. And if I don’t exist, I cannot do that act. So to exist is to appreciate whatever happens. What happens doesn’t happen only now. That’s what I like about art: questioning time. Originality, genius, “self-made”—I want to get rid of that. My face is the face of my mother and father. People tell me: you look like your mama. Others: you look like your father. So who is me? Me is them. So every moment you live contains billions of years. Cosmos, earth, all of that. I’m blessed to meet someone—from the same continent, from this earth—and we hug. That act is thanks to millions of years. And the future will be affected too. Artwork lives with people. It has life because people see it—visual energy. It doesn’t stay just here. It’s the past, now, and after.

That’s why I love the idea of a fluid conversation. I don’t need to calculate my words. Even in art: if you think you know so much about aesthetics and art history, you go to the studio and do a masterpiece—forget it. You have to go and hope something happens. In the end, it’s emotions. So, this kind of political fluidity is something that really makes sense for me. And then I can be angry and I can be sad, because I’m very interested in melancholy. I couldn’t be selling chicken and be melancholic. I couldn’t be painting cars and be melancholic either—people would disappear, I would have no clients. But here, in art, I can allow myself that space. I can deal with existence the way I want. It’s about ideas, yes—but in the end, it’s about emotions. And right now, it’s only emotions.

You talk about melancholy, yet your colors are vibrant.

It’s like intimacy. Intinmacy is not always a small space. A big space can be intimate. That’s why I love Richard Serra’s work. It can be scary, yes. Conceptually it can be made to feel that way. But the intimacy is political: you enter a big space and you feel alone, you feel with yourself. Bright colors can also represent melancholy. Look at something like Mickey Mouse: it belongs to kids, it’s supposed to be innocent, but it can also carry something spiritual, sleepy, otherworldly. That’s what I like: how something small, peripheral, can carry depth. It’s like giving value to negative space, not only positive space. Taking what is considered marginal and turning it into something central—like making the periphery into gold. Even the way some people from the ghetto wear gold is a powerful metaphor: an incredible juxtaposition. You expect brokenness, but you see brilliance. That tension speaks.

If I don’t make art, I become extremely agitated.

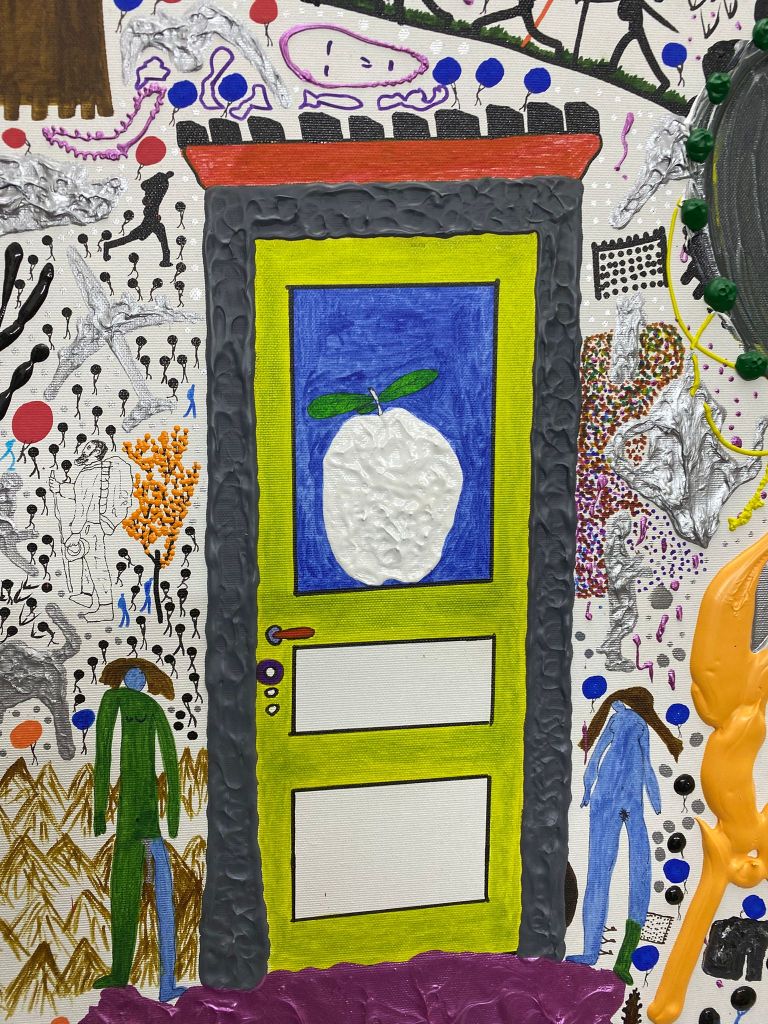

Can you tell us about this particular artwork?

I was thinking about my grandmother, for example, and at the same time I was thinking about the Nazi army. Casablanca was a strategic place during the war—intelligence services, conflicts, movements, all of that passed through there.

And I imagined this: what if, just before my grandmother got married, a German soldier had come to Taroudant, driven all the way from Germany to Aounus? What if he had seen my grandmother, fallen in love with her, married her, and taken her back to Germany? She would have had other children—but maybe I would not exist. Because she would not have given birth to my father. So who would I be then? I wouldn’t be Mohamed. This kind of thought experiment—this rebuilding of history—is exactly what art allows. Art gives you the right to remake stories, to reconstruct existence itself, both as decomposition and composition at the same time.

You mentioned your parents’ divorce and growing up in the street. Is art a way to heal this trauma?

It has something to do with healing, yes. But if it were simply healing, I would do it for two years and then I wouldn’t need it anymore. I always need to do this. If I don’t, I become extremely agitated. It’s a process. Real healing, in a way, only comes at the very end—when you die, when you take the last pill, the final medicine. Martin Heidegger said something very important: the deeper you go into something, the more complex it becomes. You think that by going deeper you will finally understand—but in fact, the more you understand, the deeper it goes. That’s why I need to do this. My body needs it. I feel it in my bones.

Artists are often afraid to talk about happiness, as if everything must be difficult, heavy, complex. And yes, the process is complex—chemically, emotionally—but happiness exists. At some point, something is reached. Sadness comes to me because I don’t confront those who hurt me with a Kalachinikov. I sit with paper and canvas. I work with something fragile, something sensitive. I’m not hurting anybody. That’s how I deal with tragedy: by confronting it, not by trying to erase it. By having a conversation with it. I have many psychiatrist friends, and the best of them always say the same thing: all we have is our life. You can take it and become a horrible person, hurt others—or you can take it as material to understand how to deal with human beings. Art is exactly that: dealing with life, with existence, with human beings. So yes, if I don’t hurt anybody, that is also therapeutic. That is healing. Because if you answer pain with pain, nobody heals—you only keep hurting each other. In the end, the hardest thing in existence is to find a solution.

Talking about emotions, what emotions would you like to transmit through your art?

Emotions of what happened, and about what is still happening. There is a Sudanese poet I deeply admire, Mohammed Jammah, who said: “Nothing hurts more than the scars of the soul.” The body is only skin, in a way, with everything it carries. But behind it, there is a soul. And when the soul is wounded, you carry it with you through life. That’s why, for me, the greatest goal is simple: not to become a horrible person. I don’t believe that having suffered gives you the right to make others suffer. If I have known pain, it is so that I can try—through my art, if possible—to open an honest and meaningful conversation.

Your work is full of hybrid animals and fantastic figures, very crowded compositions. What do they represent?

It represents that so much is happening. If I want to be clear, I cannot point to one original scar, one reason why things happened. That’s why I go everywhere. I act on positive space and negative space. That’s existence. The eye doesn’t like confusion. The eye loves positive space: you say “I get it.” Historic painting is about managing space, putting important characters in the middle, organizing the image so it is understood. That’s not what I’m interested in. I’m interested in misunderstanding—not catching the truth—confusing the eye, making it difficult for the eye to catch one element and say: “I got the truth.” And the market is extremely important for me. I spent around twenty years in the market. I sold shoes, jewelry, ceramics, carpets, caftans. The market is full of colors, full of crafts. The dream of the workers is the market to be full of people—so everywhere is full, negative space and positive space. I would love someone to come to my work and feel: it’s like a market. But I don’t like illustration. I don’t want to transform the market into a simple picture of the market. The market is complex with a juxtaposition of emotions, hate, love, jealousy. And that makes you rethink about beauty about ugliness about everything else. I did many jobs too—buildings, farms, garbage collection with a donkey. Every job teaches you something about art. You can understand people through their garbage bins. Every job has responsibility. That’s why I prefer being a reader rather than a researcher. A reader can read anything without a goal. You never know what emotionally will shock you and make you learn something. That fluidity and complexity depicts in my work.

Your work seems lively and vibrant, with so many elements that it could be hard to grasp. How does all that connect to everything you’ve experienced?

When I was trying to catch what happened between my mother and my father—the divorce—I talked to my grandmother: “I want to know what happened.” But everyone told different stories. I never once in my life saw my parents together for a meal. That was the hardest thing. It’s my right as a child, but impossible—culture, taboo. I really wanted to grasp the truth, but it kept slipping away. Then I understood philosophically: that’s also history, that’s humanity. You can’t give one sharp perspective on why we fight, why there are wars, revenge—all that. There’s no fixed idea.

How did your artistic journey start?

I grew up in a city where art is everywhere. We’re craftsmen. From a very young age, you learn how to work with your hands. I’m a cobbler — even today, I know how to make shoes. In my town, limestone sculpture is very important. I learned to carve stone as a child. It was something we did during the summer, after school. This tradition is very old. It’s part of who I am. I started sculpting very early. One of my first pieces was a portrait of my grandmother. At that time, I didn’t know what being a professional artist meant.

For me, it was just a craft. I made a lot of pieces and sold them in markets for almost nothing, often without signing them. Today, many of those works are in European homes. I think art is something you carry inside you. You learn it by observing, by watching everyday life. Creativity comes from very simple things. Emotions, expressions, metaphors — they’re everywhere. The difference is the moment when you realize that all of this is actually a world in itself.

To conclude, could you tell us about the artists who have influenced you most, and how they have shaped your own work?

As for artistic influences I have a deep love for Jean Dubuffet, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Rose Wylie, and Phyllida Barlow. Louise Bourgeois also influenced me deeply, especially in the way she explored family, jealousy, intimacy, and the emotional complexity of what we call “home.” A house is just a building, but a home is full of emotions. And Cézanne taught me a great deal about space and the way he dealt with objects.

DakArtNews extends its heartfelt thanks to architects Lubna Tuzani Idrissi and Yasmina Echair, as well as curator Aniko Boehler, for arranging this studio visit.

Leave a comment