Bara Diokhané embodies the roles of art collector, filmmaker, painter, activist, and lawyer. Nicknamed “the lawyer of artists,” Bara Diokhané has long advocated for the recognition of artists and their role in socio-economic development. His latest film, Amoonafi (“It Happened Here,” in Wolof), sheds light on the contribution of cultural actors to the development of Senegal over the past fifty years. DakartNews had the privilege of being received in his home, located in the heart of downtown Dakar. A true artistic sanctuary, the walls of his house are adorned with works by numerous artists including Senegalese artists, those of the pioneers of the country’s first generations of painters. As the Dakar Biennale unfolds in full swing, Bara shares, in this interview, his thoughts on the event’s significance, its evolution over the years, and the state of contemporary art in Senegal. Through his reflections, we gain insight into the intersection of culture, politics, and art, as well as the challenges and opportunities that the Senegalese art scene faces today.

The Dakar Biennale is in full progress at the moment. What is your perspective on it?

I notice that this year’s guest country is the United States. This takes me back to the 2002 Biennale, during which I organized an OFF exhibition. At that time, the Biennale’s statutes only allowed the participation of African artists living on the continent. I made it a point to include African artists living in the U.S., as well as Jamaicans, South Africans, and African Americans. Significant progress has been made since then—from having to fight to showcase artists living outside Africa to 2024, where the United States is one of the guest countries. I see this as a significant step forward in terms of openness. While the Biennale is undeniably a flagship event in contemporary African art, it is time for Senegal, which has hosted this event every two years for the past 32 years, to reflect on its true impact. What is the state of art in this city? Is there a decent art school in Dakar, a city that welcomes the world every two years? The answer is no. Dakar does not have an art school worthy of its rank and status as a capital of contemporary African art. Additionally, there should be statistical work to measure the Biennale’s contributions to tourism, artists, and the art market. Social and educational aspects must also be considered. Art and culture have many branches that need exploring. However, I do not have access to this data. When you compare Dakar to Venice, the difference is clear. In Venice, you feel like you’re in a Biennale city. This is evident in the shops, the merchandise sold—everything is art. Art souvenirs and reproductions of masterpieces are readily available. I do not see such activities surrounding the Dakar Biennale, even though it has existed for quite a long time.

Do you think the local population is not involved?

I am not qualified to comment extensively on the Biennale as I haven’t seen everything. I spent 20 years in the United States. That said, I read an interview with the artist Zulu Mbaye, who mentioned that local artists feel left out. If Senegalese artists believe they are ostracized, particularly regarding the international exhibition, it is likely even more complicated for the local population. Dakar needs to embrace its identity as a Biennale city. The Biennale can bring immense value—it’s not a fair or carnival.

How do you assess the chosen venue for the international exhibition?

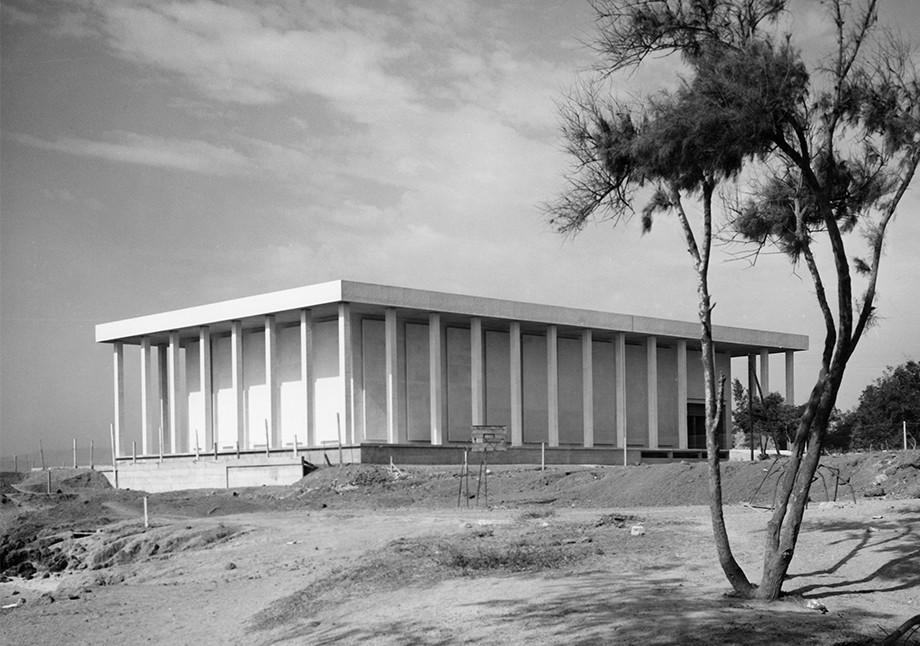

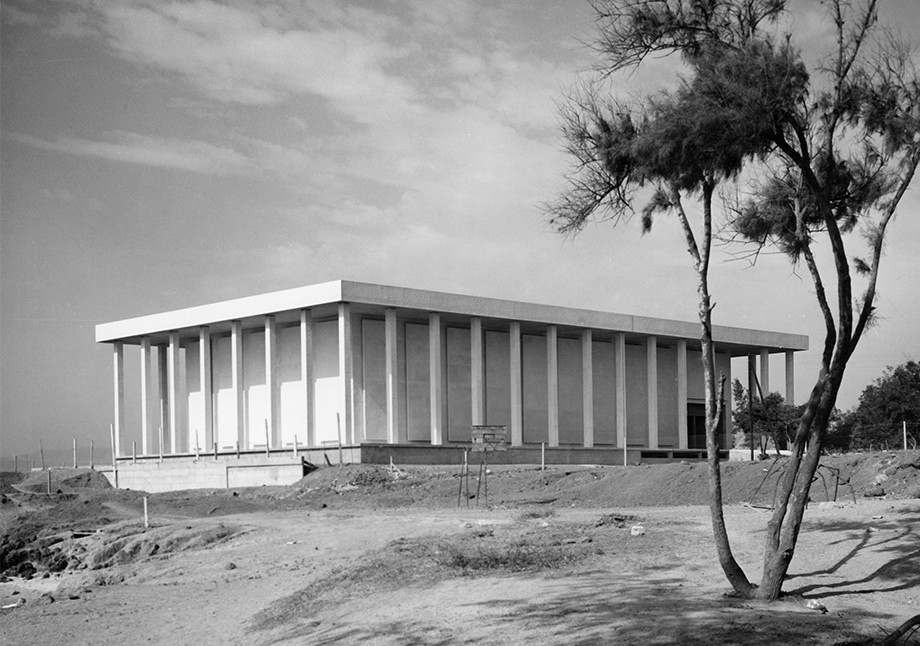

It makes little sense to organize the Biennale in a former courthouse. It wasn’t designed for that. The architects who built the courthouse certainly didn’t envision it as an exhibition space. During the first World Festival of Negro Arts in 1966, the contemporary art exhibition was held in the courthouse, while the traditional African art exhibition took place at the Musée Dynamique—a building now occupied by the Supreme Court. However, a courthouse is not a museum, and the Musée Dynamique is not a courthouse. This reflects the paradox of our institutions. The Musée Dynamique was derailed from its intended trajectory due to an occupation that makes little sense.

How did the Musée Dynamique end up being transformed into the Supreme Court?

The justification given was that the original courthouse in Cap Manuel was at risk of collapse and unsafe. As a result, the Supreme Court temporarily moved to the Musée Dynamique. It was stated that they would only remain there until a new courthouse was built. This new courthouse in Rebeuss has since been constructed, yet the Supreme Court still occupies the Musée Dynamique. This situation has hurt both the art world and the judiciary. What was supposed to be a temporary arrangement has lasted more than 30 years. Dakar has lost its status as the first African city to host a museum of contemporary art. Now, that title is claimed by the Zeitz MOCAA in South Africa.

Despite a 1996 decision by President Abdou Diouf to return the building to the Ministry of Culture, nothing has been done. How do you explain this?

Senegalese culture suffered after the departure of President-poet Léopold Sédar Senghor. He was sensitive to cultural matters. Political will is crucial to recognizing culture as a fundamental lever for development—not just culturally but also economically and socially. It must be implemented through exhibitions, education, infrastructure, and measurable outcomes.

The Agit’Art movement, which opposed the academic orthodoxy of the School of Dakar, did it regret Senghor’s departure?

Absolutely. They were always on the margins of the School of Dakar. Being on the margins of the School of Dakar and wanting to live off their art was not easy. This was the case for Mor Faye, who was among the artists who distinguished themselves from the aesthetics of Négritude. Négritude had its leading artists who travelled, received scholarships, were collected, and even exhibited by President Senghor during his travels. One day, I was told that Picasso and the Queen of England had Senegalese artists in their collections—works given to them by Senghor when he travelled. Senghor was an interesting art partner, but he had his own vision, which not everyone shared. So, in a sense, those who rejected the aesthetics of Négritude had greater creative freedom. The others might have gained material benefits, but they were confined within a certain aesthetic.

After Senghor, how did the members of the Agit’Art movement negotiate their relationship with the new government of Abdou Diouf?

Let me tell you an anecdote. Right after Senghor’s departure, the law enforcement invaded the Village des Arts (which was in an old military camp in downtown). They destroyed everything and expelled the artists. To resist, the artists exhibited outside, in the streets. Someone told me that the Swiss Ambassador stopped to see and buy a work from an artist named Mbaye Diop. After negotiating the price, the ambassador pulled out his check, but Mbaye Diop replied that he didn’t accept checks. He said he didn’t have any cash and would come back later. All of this was happening under the watchful eyes of the police, who were keeping an eye on them to make sure they wouldn’t return to the village. The next day, the ambassador sent a bag with money—2,100,000 CFA francs (3,360 dollars) for three pieces. The police were astonished because they saw the artists as beggars. This was surely reported. And that’s when the authorities slightly cooled down their enthusiasm. They said they would take their works and keep them, as it was raining. This gives you an idea of the rupture that occurred after Senghor’s departure.

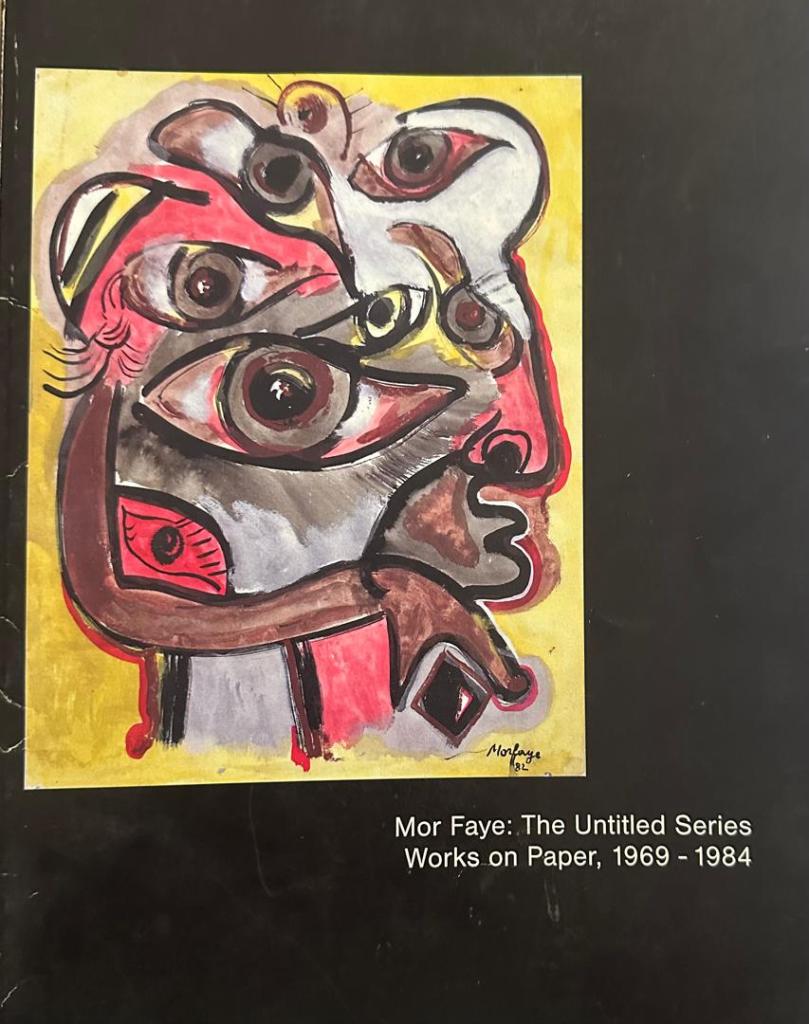

What characterized, in your opinion, the artistic philosophy of Senghor and that of the artists of the School of Dakar?

As you know, Senghor believed that emotion is “Negro.” He thought that one must bring out the “Negro” sensitivity. According to him, it wasn’t even necessary to know how to read French or study the history of art. That was his philosophy. And this was reinforced when he brought Pierre Lods, the founder of the Poto-Poto School in Brazzaville, to Senegal. On the other hand, there was Iba Ndiaye, who believed that one had to learn art. Iba Ndiaye had students like Mballo Kébé, Mor Faye, and others. And you could see it in their formalism. Looking at the works of Iba Ndiaye’s students, you could tell they had studied the history of art; you could feel that they had studied certain artists. Meanwhile, the students of Pierre Lods expressed themselves freely. It must be said that the artists of the School of Dakar had a different artistic approach depending on whether they were students of Pierre Lods and Pape Ibra Tall on one side or Iba Ndiaye on the other. Both branches claim to belong to the School of Dakar, but aesthetically, they have nothing in common.

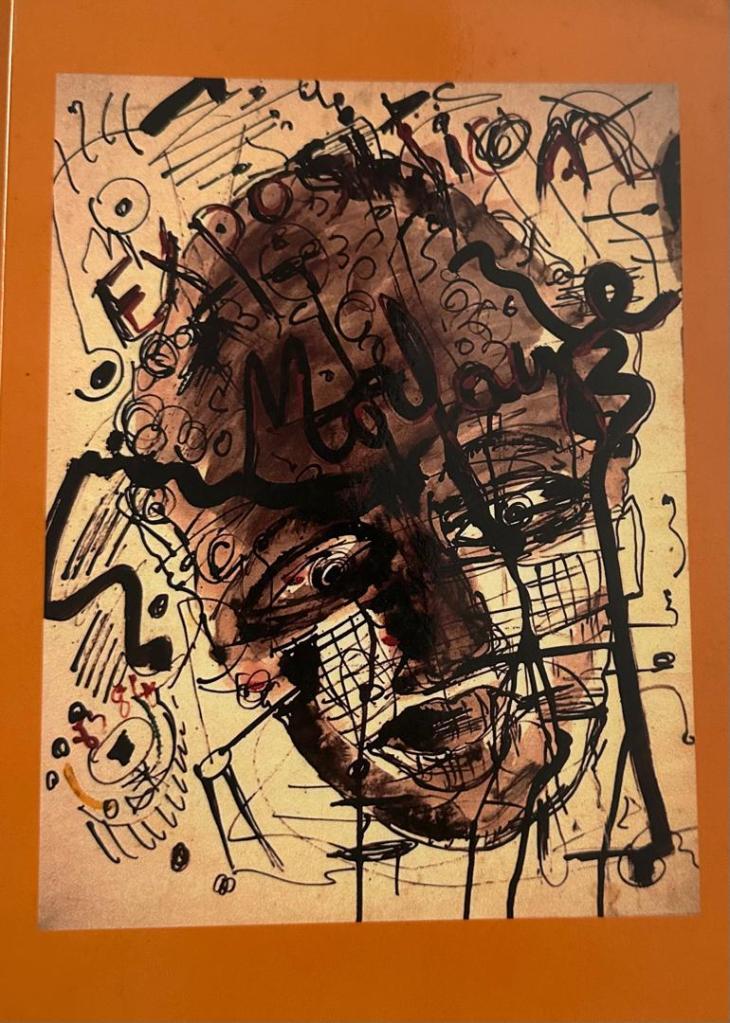

The Warrior, Oil on celotex

134 by 104cm

At one point, some thought the School of Dakar was pompous and that Senghor, a Francophile, simply wanted to create a school in the image of the School of Paris. It must also be noted that the dominant trend was that of Pape Ibra Tall and Pierre Lods. Iba Ndiaye even resigned and returned to France. He did not believe in an artist who did not master certain pictorial techniques, the history of art, and so on. He wanted to pass this knowledge on. This did not prevent the Musée Dynamique in Dakar from hosting the first retrospective exhibition of Iba Ndiaye in 1977, an exhibition inaugurated by President Senghor and his wife. It was his grand return after his withdrawal.

How did the later generations differentiate themselves from their predecessors of the School of Dakar?

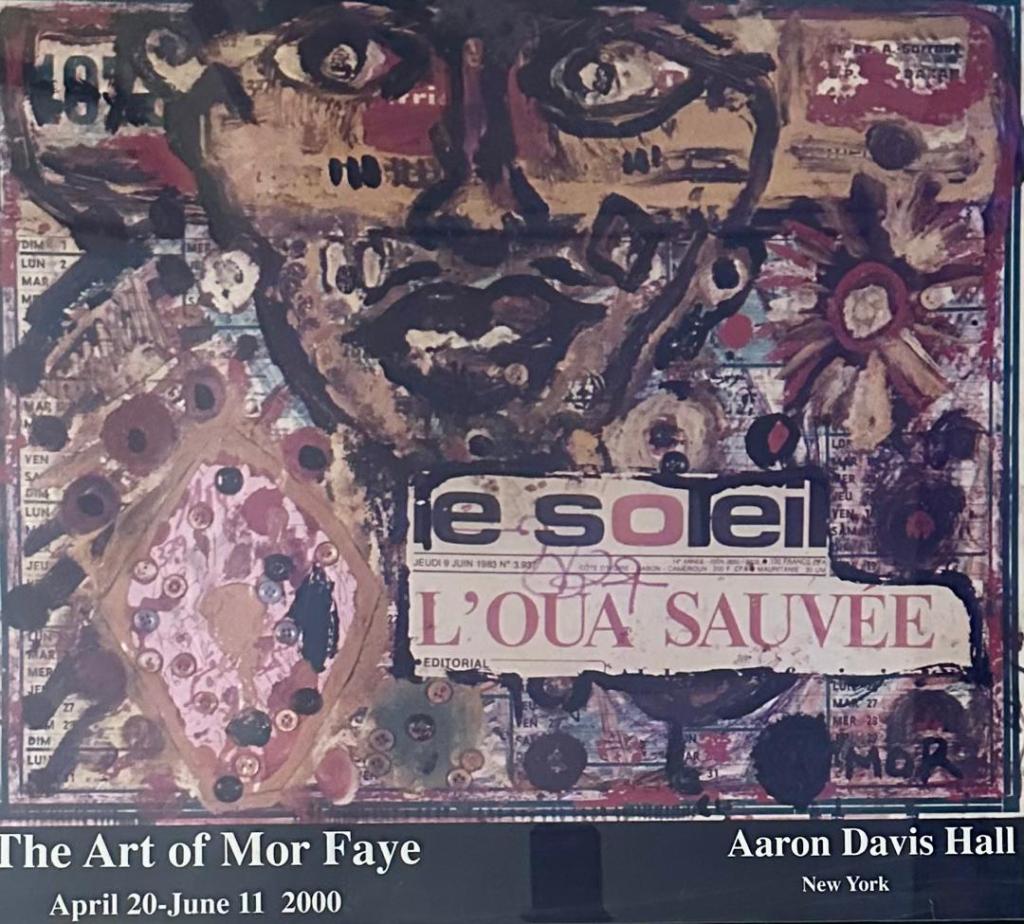

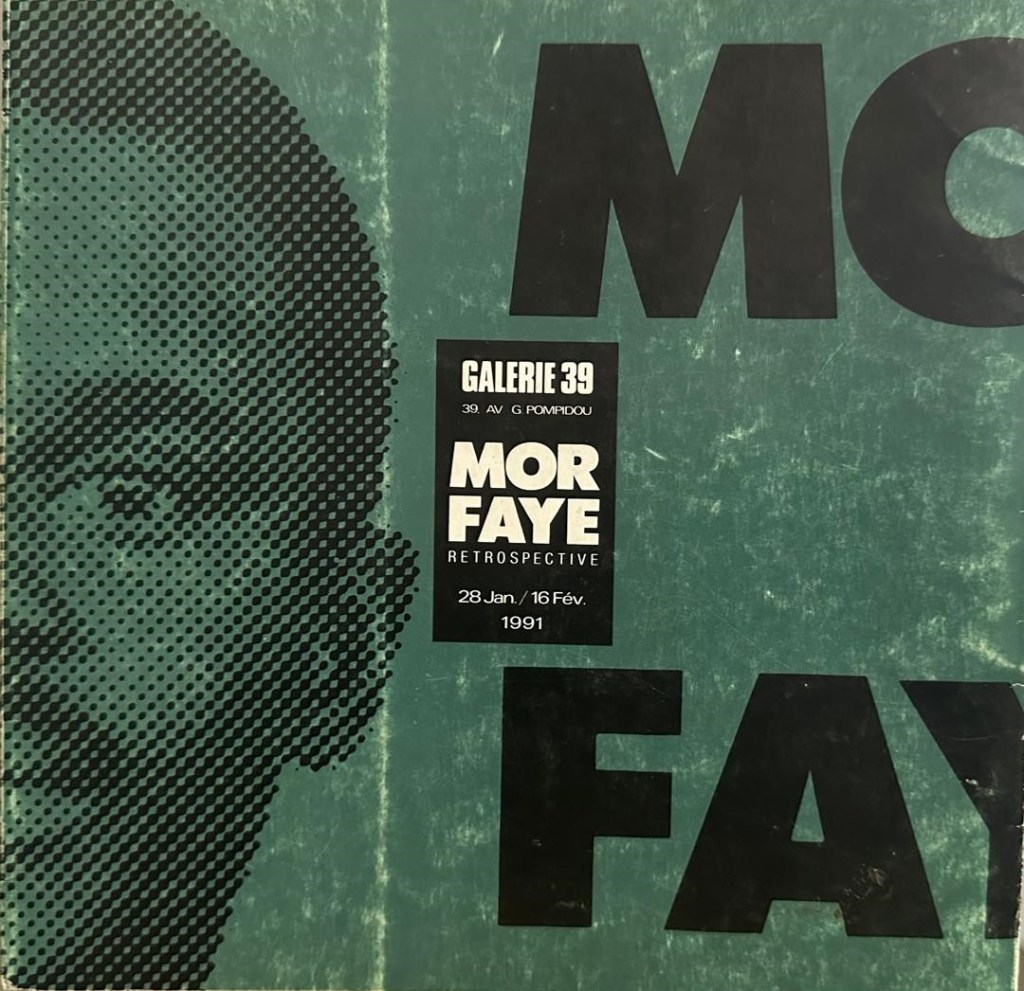

I think there was a moment of rupture, particularly thanks to the exhibition of Mor Faye. In 1991, I organized an exhibition for Mor Faye, which was a popular and commercial success. The majority of the buyers were Senegalese. This created a trigger for many artists, who saw that a marginal figure from the School of Dakar was able to sell his work. It demonstrated that the aesthetic of Negritude was not the only path.

What are the themes that connect the artists of the School of Dakar to the new generation?

What the artists have in common is the territory, the issues of development, health, and the environment. These are shared by everyone. Now, how these themes are expressed in their work—that’s where creative freedom must be asserted.

Personally, which artists have made the most impression on you?

There is Mor Faye, for his talent, and I collected his entire collection. His work was exceptional. When he was 15 or 16 years old, he won drawing and modelling prizes at school. He was a student of Iba Ndiaye, so he learned the history of art and fine arts. His vision is very broad. What interested me was his freedom of expression and his way of confronting his knowledge of Western art with his African cultural resources. He achieved a balance by creating interesting works, particularly during the apartheid period, where he created a series that makes you think that the person who made it certainly knew Picasso’s Guernica. He addressed the horrors of apartheid in a visual way, using the colors and rhythms of Africa. But very early on, I had artist companions like El Hadj Sy. We are the same age. We used to meet up. I would go to the Village des Arts to watch him paint, and he would come to my house. Later, I started buying his work and bringing friends who also bought pieces. Joe Ouakam was also a companion. I’ve known many, but the one I collected and for whom I became involved in making him known to the world is Mor Faye. He made me transform into a curator, an artist agent, a promoter. Bringing him to the Venice Biennale or to a museum in New York, while his works were poorly preserved in a slum, was quite a journey. We can no longer talk about contemporary African art without mentioning Mor Faye.

It’s said that he had issues with depression and was at odds with President Senghor.

There are many myths surrounding him. It’s said that one day he went to protest in front of the Palace, and Senghor asked that he not be beaten and that he be given materials to paint. It’s true that he suffered from depression. He taught art at High school. Among Mor Faye’s notable students are painter El Sy, jazz musician and educator Pascal Bokar Thiam, and Amadou Diaw, Director of the Museum of Photography in Saint-Louis, Senegal. But when he had his bouts of depression and was taken to the Fann hospital, in Dakar. Even there, the psychiatrists, knowing his talent, tried to use his art as therapy. Art therapy—he was one of its pioneers there. He held exhibitions in the hospital.

To conclude, what do you think is needed to restore Senegal’s former glory in the field of art?

First and foremost, and what we lack, is historical awareness of art in Senegal. We don’t have the awareness that art is as important as other sectors such as oil or maritime industries. The same level of energy is not dedicated to art. There also needs to be an enlightened cultural policy. In Senegal, the new administration no longer has a ministry dedicated solely to Culture. Instead, cultural affairs have been integrated into the Ministry of Youth and Sports. We need a government that understands the stakes of culture, not only in terms of the economy but also in civics and identity. This is a policy that must be carefully developed and applied. When a well-known filmmaker tells me that in his entire life, he has never received a penny in royalties in Senegal, even though he made some of the most popular films in the country’s history, and then dies at 85 without being able to afford his prescriptions—that’s a problem. How did he end up in this situation? There are things that are missing, things that need to be put in place. I read with a sense of both satisfaction and a bitter smile that a decree has been signed concerning private copying. This is a law that dates back to 2008, and it’s only in 2024 that the implementing decree is being signed.

Read also:

The World of Senegalese Contemporary Art Through Sylvain Sankalé’s Eyes

The State of Contemporary African Art Today: Dr. Ibou Diop’s Critical Perspective

Why Dakar Stands Out in the World of Art! A Conversation with Wagane Gueye

DAkArtNews

Leave a comment