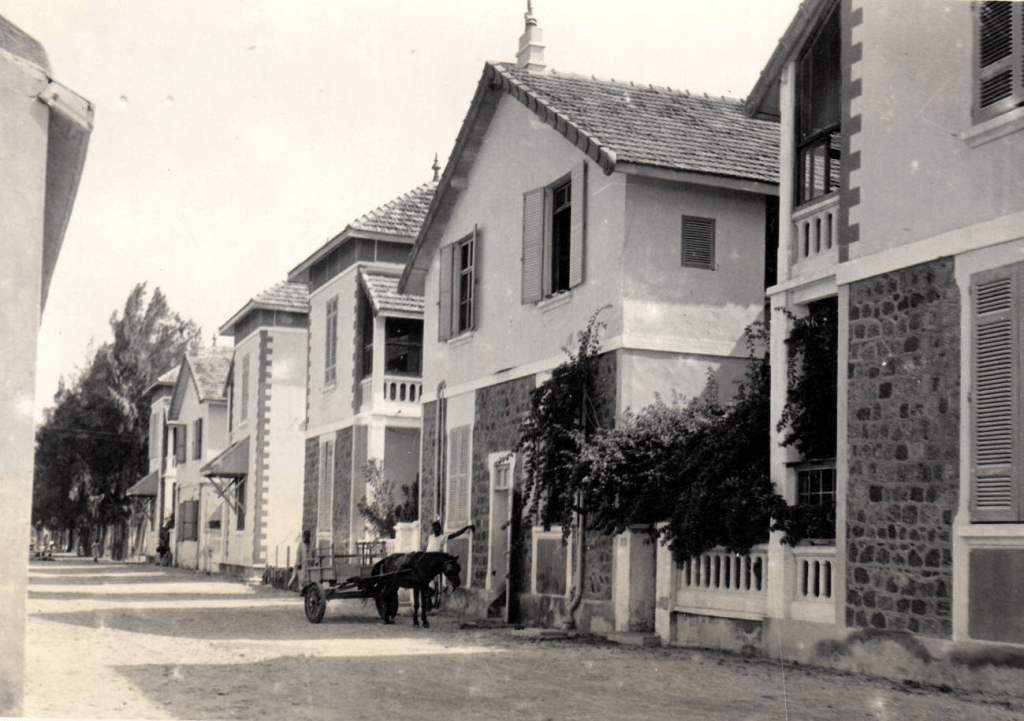

Few cities in West Africa carry the weight of memory quite like Saint-Louis. Perched on an island at the mouth of the Senegal River, this UNESCO World Heritage site was once the colonial capital of French West Africa, a cosmopolitan port where African, European, and American currents converged. Its arcaded houses, wrought-iron balconies, and ochre façades still bear the patina of empire and trade, whispering stories of migration, commerce, and cultural fusion.

Photography, too, found fertile ground here. In the mid-19th century, not long after the invention of the daguerreotype in France, the new medium traveled down the Senegal River to Saint-Louis. Local studios quickly flourished, producing portraits of mixed-race families, Moorish traders, and colonial officials, as well as intimate images preserved in family albums. By the early 20th century, Senegalese photographers such as Meïssa Gaye and the Casset brothers had established themselves, creating visual archives that continue to shape the collective memory of the nation.

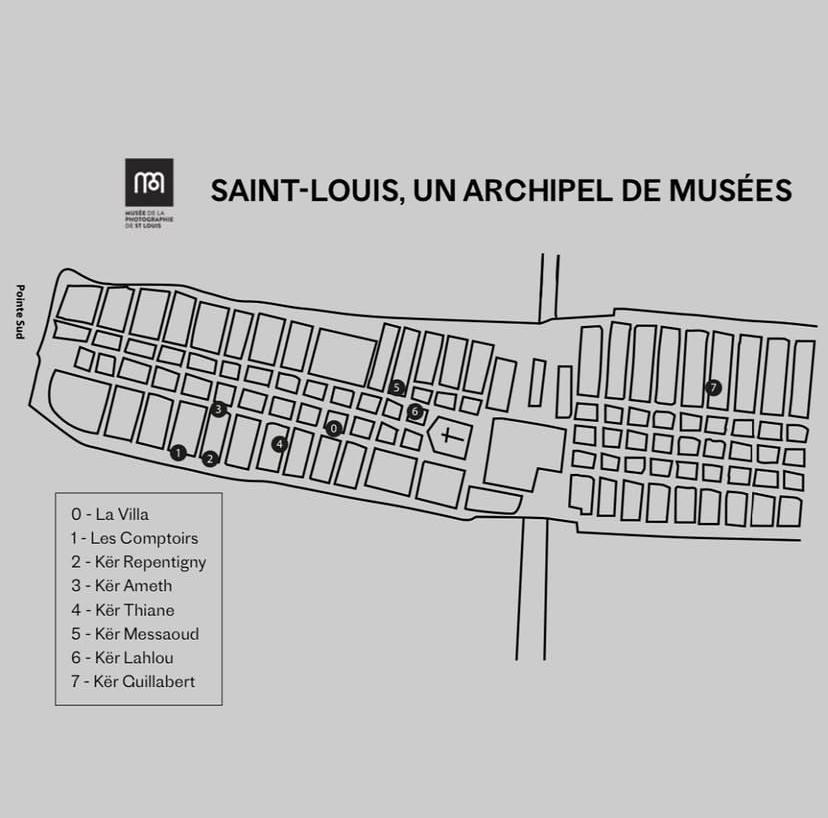

Into this storied city steps Amadou Diaw, 64, who in 2017 founded the Museum of Photography of Saint-Louis (MuPho), West Africa’s first museum devoted entirely to the art of photography. Conceived as an “archipelago of houses” woven into Saint-Louis’s streets, the museum is composed of seven renovated homes that mirror the city’s intimate, interconnected spirit, displaying colonial-era daguerreotypes alongside independence-era portraits and the bold visions of today’s African photographers.

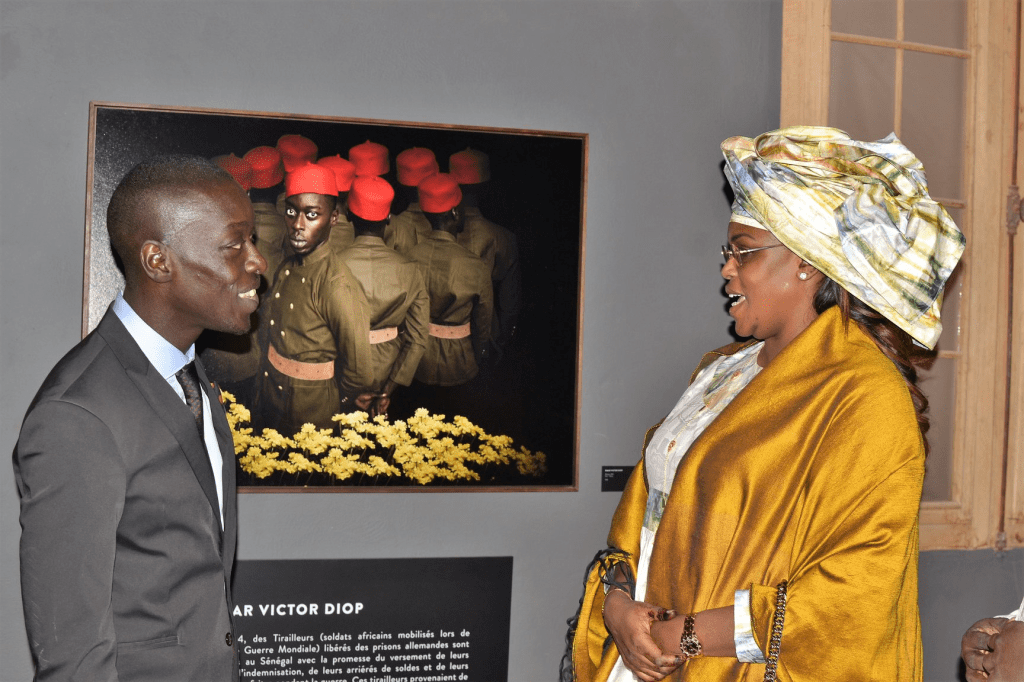

Amadou Diaw, MuPho’s founder, a collector, patron of the arts, and the mind behind Senegal’s first business school, spoke with DakArtNews about his vision. A lifelong steward of cultural memory, he sees Saint-Louis as both a living city and a museum, where photography remains its most eloquent language.

Saint-Louis is often described as the visual memory of Senegal, because of its pioneering role in the history of West African photography. What does your own memory of the city look like?

It may come as a surprise, but I spent most of my life in Dakar. I’m a Saint-Louisian by culture, family, and education, but my life has largely been in Dakar. Like many of the families of Saint-Louis, after the capital was moved, we relocated to Dakar. Yet every school break—Christmas, Easter, summer—we had to return to Saint-Louis. In Dakar, we received instruction, we went to school; in Saint-Louis, we received family, religious, and cultural education. My Saint-Louis imaginary was built on this constant return, whether by shared taxi or by train, to complete my upbringing.

For me, every street in Saint-Louis is like a movie set. The characters—the old Mauritanian in his little shack, the jeweler with his skillful hands and the flames behind him, the Moorish trader with his colorful goods, the elderly woman smoking her long pipe—were all extraordinary actors. It wasn’t until the end of my teenage years, when I became a student, that I truly learned to love this city. Ever since, whenever I have free time, I return to Saint-Louis. These scenes of daily life feel like photographs to me. When I invite people to open doors slightly, to glance into Saint-Louis courtyards, everything is there to be captured. This city runs through my veins; it nourished my education.

How did this memory inspire the creation of the MuPho in 2017?

In Saint-Louis, we live through stories. Families are constantly recalling: “Do you remember the old man who used to do this?”, “The lady who lived there?”, “The mixed heritage elder in the neighborhood?” These stories shaped me. I was a collector of contemporary art—paintings, sculptures—but I realized that the scenes of Saint-Louis, those characters, were already art in themselves. Then I met Laurent Gerrer, a photographer who traveled across Africa and eventually settled in Saint-Louis. His images of Senegal, and especially of Saint-Louis, struck me deeply. While digging through old family trunks in Saint-Louis, I came across extraordinary portraits signed by Meïssa Gaye, the Casset brothers, and other great Dakar-based photographers. I thought: this needs to be shared with the world—the modern-day scenes I see, the old portraits found in family albums. That’s how the MuPho was born.

Your initial vision for MuPho was about sharing?

Yes, it was all about sharing. MuPho is about showing the world what shaped me, what defines Saint-Louisian culture. These everyday scenes, these old portraits, they needed to be presented under one single word: sharing.

Eight years later, in 2025, has that vision come true?

More than ever. I won’t give a percentage, but the number of tourists who come to Saint-Louis specifically for MuPho, for this “archipelago of museums,” is impressive. They know we’re offering something unique. Scholars, writers, thinkers come to Saint-Louis, often because they’ve heard about this space of sharing. It’s a reality, a fact. The vision has come to life—and now we need to think about the second step.

And this next step, does it mean geographic expansion, new collections, or international partnerships?

The second step is preparing for 2027. That year, we’ll celebrate the museum’s 10th anniversary. Preparations are already underway. Last April, I was fortunate to host several curators, including Sara Catalán from the Barcelona Biennale, along with Tania Safura, Cindy Sissokho, Camille Ostermann, and Amina Belghiti. Together with them, and with the Raw Material Company team, we started imagining the museum’s future.

“A scattered museum means showing Saint-Louis in its entirety: two and a half kilometers of life to experience.

On a continent where memory is often transmitted orally or through family archives , what convinced you that a museum was the best way to preserve and tell this memory?

A museum is the right tool. It concentrates memory and history, and makes them accessible. At MuPho, people learn about Senegal and Africa through photography. We tell the story of independence through images—a history that is authentic, documented. It’s the simplest way to share with others. And we make sure the space is welcoming, that conditions are pleasant so that everyone feels comfortable coming.

You chose a dispersed museum, an “archipelago of houses,” rather than a monumental building. Was this your way of saying that memory can’t be contained in a single box?

It’s even more than that. What I want to show to the world is Saint-Louis itself—its history, its archives, its memory. A scattered museum means showing Saint-Louis in its entirety: two and a half kilometers of life to experience. Visitors have to walk through the city, live it, appreciate it. The photographs we exhibit are meant to be lived, not just looked at.

Photography is sometimes accused of fetishizing Africa, reducing it to exotic clichés. How does MuPho avoid this trap?

Through contemporary photography. Old photos are a treasure, but they can be a trap if we stop there. By opening ourselves to modern photography, we escape that trap. For example, we curated an exhibition called “Reveries of Yesterday, Dreams of Today, Promises of Tomorrow.” The reveries of yesterday are still there—after all, Saint-Louis is a city where people live very much in the past. But we highlight today’s dreams through contemporary works, so as to avoid exotic clichés.

We showcase the extraordinary vitality of young Senegalese and African photography. I truly discovered contemporary African photography through Salimata Diop, another Saint-Louisian whose career I deeply admire. I immediately trusted her to direct the museum at its founding. Over the years, many young photographers have entered my circle—my former student Omar Victor Diop, as well as younger talents like Layepro and Badara Preira. Among those close to me, there’s also Massow Ka. There’s an incredible Senegalese blossoming—Bineta Diaw, Ina Thiam, to name just a few.

By exhibiting colonial archives, 1960s portraits, and contemporary works side by side, are you rewriting the history of Senegal in images?

The history is already there. MuPho is a space where we show Senegal’s history through evidence, because history has often been rewritten by various groups. Old and modern photos together tell the true story of Senegal—our past and our present.

You’re also a passionate collector. Is there one photograph you acquired for MuPho that you feel particularly attached to?

They all matter to me. Wildfire by David Uzochukwu, featuring a woman with flaming hair, is incredibly powerful. There are also recent acquisitions that stand out. And there’s a loan from Delphine Diallo, a Franco-Senegalese artist from Saint-Louis, whose work on ancient and modern hairstyles is extraordinary. Delphine set out to conquer the world and then came back—her work embodies that return.

We sense a certain pride when you talk about Saint-Louis.

That’s typical of Saint-Louisians. It’s not exactly pride—it’s our history. Even though I didn’t grow up there, every minute I spent in the city counted. There’s a tremor in our voices when we talk about it, because we’re reliving the scenes that shaped our childhood.

“Art must play a greater role in our education systems.

During our visit to Saint-Louis, we noticed that most of MuPho’s visitors were tourists or foreigners. Do you share that observation? What categories of audiences have you identified?

Yes, tourists are definitely there. But there’s also local tourism, especially during certain times of year, like August. It depends on the season. Of course, we would like more of the local community to come. They do participate in our events, but we’d like them to take more ownership of the spaces. There’s work to be done. As for the categories of visitors, I’d say first the students. Then tourists, teachers… yes, that’s about it. There’s still a lot to do.

In your view, what needs to be done to attract more of the local population?

We need to raise awareness from the ground up, in schools, about the arts and sciences, which are often neglected. We need strong, visionary leadership and innovation. We dream of large spaces where everyone finds their place. Arts and sciences are the foundation to build on.

You also created the Saint-Louis Forum, an interdisciplinary exchange platform, at the same time as MuPho. What did you feel was missing in Senegal, or in Africa, that the forum needed to address?

The Forum was designed to bring very different people together at the same table. Too often in Senegal, you’d see union leaders on one side, doctors on another… For me, we needed to bring everyone together: sports, economics, finance, education… And that’s what we succeeded in doing. Three editions, three successes I’m proud of. For me, dialogue must be open to all, but especially at the state level. Our leaders across Africa must open up, must talk to everyone. Good leadership includes everyone.

What is the common thread between MuPho and the Saint-Louis Forum?

My conviction is that art must play a greater role in our education systems. That’s the role of museums. Museums also work on the history of our countries and continent. The Forum fits into that same vision. It’s an intellectual and visual memory we are building—we filmed what we could, but that’s only one step. The Forum is a step along the way, and we must continue.

“At this age, I feel the need to learn more from others, from young people, from elders.

In 2050, when people talk about Saint-Louis, do you want them to remember it as the city of the Forum, of MuPho, or both?

As Saint-Louis, simply. Saint-Louis as a cultural hub, a place of exchange and encounters. Islands that are developing, economies sustained by culture and by the meetings initiated through the Forum.

You are at once an entrepreneur, educator, and patron of the arts. How do you reconcile these three identities?

For me, they go hand in hand. I can’t imagine an education system without art. A strong system rests on both arts and sciences. I’ve never been able to separate them. That’s why I admire my friend Souleymane Bachir Diagne when he speaks of STEAMS: Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, and Mathematics. Arts and mathematics are not contradictory—everyone can draw a little from both.

What generation are you trying to shape—artists, managers, or simply citizens?

Citizens, first of all. They need guidance. I see myself planting seeds in children. If we want to invest, that’s where we must begin. There’s a whole generation waiting. Remember, 19 is the median age in Senegal. But everyone should engage with art and science. I don’t separate them.

If you were 25 today, would you be a photographer?

I tried. I started photography at 15. Then I moved on. I needed to excel, and that wasn’t where my excellence lay. Today, I take pictures of everything with my iPhone—I capture moments all the time.

When you’ve built, for example, a school, a museum… what more do you still want to pass on?

There is always more to give. But at this age, I feel the need to learn more. I want to learn from others, from young people, from elders. And I learn every day through the arts.

When future historians talk about you, what would you like them to say?

It would be pretentious of me to ask historians to speak of me. That’s not for me to decide, it’s for others. I only did what I could with the means God gave me—in the arts, in education, and in heritage preservation.

Read also

The Contemporary African Art Landscape with Prof. Yacouba Konaté

Africa’s Artists Deserve a Bigger Stage. Basel Is Just the Start

Leave a comment